Transport is on the front line in the war on carbon, as the world steps up efforts to reduce production of damaging greenhouse gases.

Yet while land transport — on road and rail — is racing ahead with electrification driven by government incentives and consumer demand, shipping remains wedded to hydrocarbons and has yet to address how to implement planned emission cuts.

While the Tesla X electric car was the top-selling model in Norway last month, the number of new ships delivered that are powered by anything other than fuel oil could be counted on the fingers of one hand.

In such a context, the IMO’s target to halve shipping’s CO2 emissions — to 470 million tonnes per year from the estimated 940 million tonnes emitted in 2008 — appears ambitious indeed.

“The problem is that we have built a massive sea transport system around fossil fuels,” Clarksons Research president Martin Stopford said.

Today, around 60,000 ships are moving 12 billion tonnes of cargo each year, producing about three tonnes of CO2 for every tonne of bunker fuel burned.

Stopford had doubts that it was possible to hit the IMO target when it was first agreed this year. “It struck me as an astonishing target and I couldn’t see how you could do it,” he said.

I think the world needs to sit down and ask: 'Are we really moving things that need to be moved? Are there better ways of using less carbon?'

Martin Stopford

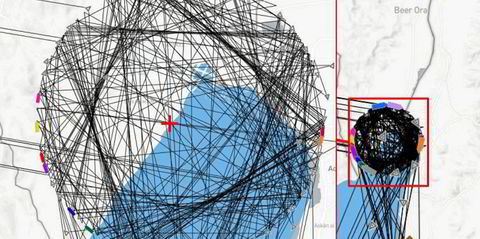

However, he has crafted a model built on extrapolation of fleet data that shows the target could in fact be reached — but not without significant restructuring of maritime transport and the way shipping is conducted.

Trade growth is key

His original analysis was presented at last week’s Women’s International Shipping & Trading Association (Wista) international annual conference in Tromso, Norway.

If growth in seaborne trade continues at the current rate of 3.2% per year, it would mean around 32 billion tonnes of cargo being shipped by 2050. To hit the IMO’s CO2 target, it would require near-total decarbonisation of ship power by that time.

However, he said if the average rate of trade growth falls to 2.2%, seaborne trade would be around 24 billion tonnes per year by 2050 — double today’s amount.

Stopford argued that physical trade growth should be decoupled from economic growth.

“We’ve spent 50 years trying to dream up ways of transporting more cargo,” he said. “I think the world needs to sit down and ask: ‘Are we really moving things that need to be moved? Are there better ways of using less carbon?’”

However, even with slower seaborne trade growth, under a “business as usual” scenario for shipping, carbon emissions to transport that volume would still hit about three billion tonnes per year — more than six times the target.

Slowing the fleet would be the crucial next step. The figure is slashed to around 1.6 billion tonnes of CO2 if the fleet steams at an average 12 knots — which is close to today’s average — and further still at 10 knots.

“Finally, by bringing in electric power, and then fuel cells from 2025, and gradually building that up, you can hit a target of 470 million tonnes,” Stopford said. “All of those, I believe, are achievable targets.”

Critical to delivering the target would be to rethink the shipping business model. “The way you might organise this, is that you try to run the shipping company as a transport factory and use information to allow everybody to be goal-orientated,” suggested Stopford, who has always taken an intense interest in education and business organisation.

“You need to rethink the organisation structure for smart management, teamwork and, I have to say, more women,” he concluded to cheers from more than 300 Wista delegates.

Such a radical approach to decarbonisation would have the consequence of creating demand for new tonnage, powered by alternative fuels.

This model suggests a surge in newbuilding over the next 15 years, peaking in around 2032.

“You mustn’t tell the shipbuilders about this scenario as, according to this, you’ve got another shipbuilding boom out there bubbling in 2032,” Stopford concluded. “You can see the future is bright. The more you do to solve the carbon crisis, the better it gets.”