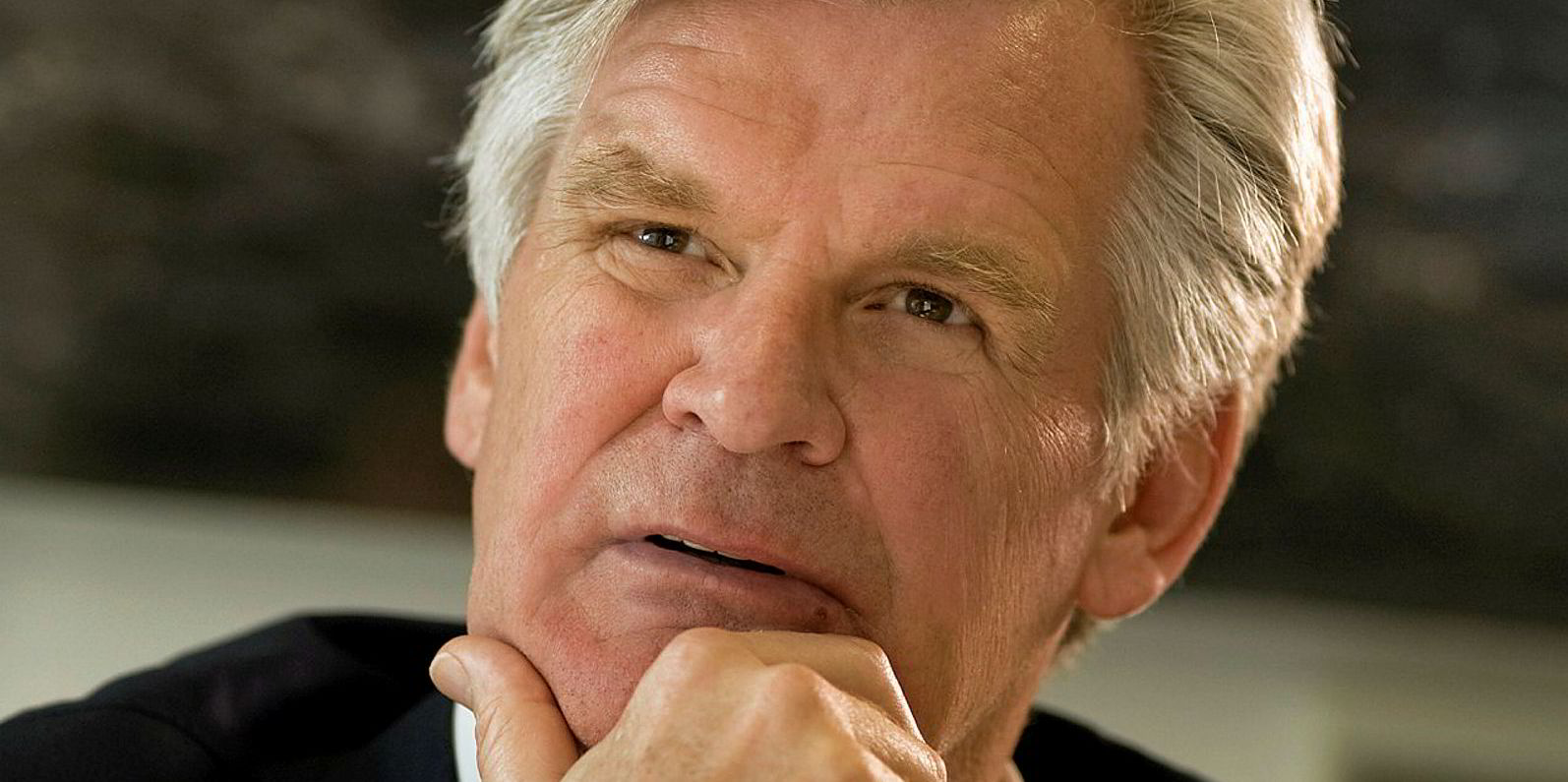

Twenty years in the LNG industry have given Tor Olav Troim a perspective from shipping, downstream into regasification and upstream to floating liquefaction.

He traces the start of his passion for LNG to his last couple of years working with John Fredriksen. “We suddenly started to see what we were really into, which was producing cheap and clean energy. Then things became exciting,” he says.

Troim chose to buy out Golar from Fredriksen in the summer of 2014 in what he admits was bad market timing, but with the attraction that the LNG sector was growing at 10% per year.

He then launched into the power sector with the 1.5GW Porto de Sergipe thermoelectric plant, Brazil’s first private-sector LNG-to-power project, which is due to be in operation by 1 January 2020.

“Then you are talking about converting stranded gas, which is not worth anything, into something which is worth a lot to a lot of people — power. That’s really where the passion came,” he says.

“My thesis is that the most undervalued asset in the LNG world today is stranded gas.

“You can buy it for less than five cents per MMBtu, and from an energy point of view it has the same function as oil. It’s just much cheaper.

“When you own something that is not valuable because the technology is not there, and then suddenly the technology comes, it gets a lot of value.”

Step forward floating LNG, in which Golar LNG has been a pioneer.

Troim studied naval architecture at university and was a classmate of Oscar Spieler, technical godfather of Hilli Episeyo, Golar’s first conversion of an LNG carrier into an FLNG unit, which began operating off Cameroon last year.

On a trip back to the University of Trondheim, the two gave speeches to students in which Spieler said he applied everything from his studies in his business career, whereas Troim said he had used nothing. “I’m not a good naval architect,” he jokes.

But technology clearly has an appeal for him.

“The technical team in Golar has done a fantastic job with Hilli. I’m super-proud of them,” he says, explaining that the floater was delivered $100m under budget, almost on time, and has now produced almost 20 cargoes.

Troim sees Golar as a reflection of the changing technologies in the industry.

The company, which Fredriksen bought from Osprey Maritime in 2000, started out in LNG shipping, with big names such as John Angelicoussis and Peter Livanos following behind.

Golar then moved into FSRUs, working alongside competitors including Exmar and Excelerate Energy before others piled in, “destroying” that market, according to Troim.

“Then we went into FLNG. This market looks pretty good, actually, but it will not be good forever. It will be good because there is limited yard capacity for conversions and there is limited capital which is willing to take that risk.” But over the next 10 years, he believes, it is probably going to follow the FSRU sector.

“People will get to know the technology and then the winner will be the guy who owns the gas reserves, or the people who produce it.”

Troim has an unabashed approach to speaking about making money, and the figures pour out of him in compelling detail.

The current returns on long-term LNG ship chartering clearly leave him cold. A Golar FLNG unit at $1.3bn costs just over six times as much an LNG carrier newbuilding. To have the same return as an LNG carrier, a floater requires a charter rate of around $310,000 per day.

“This [FLNG] business pays around $600,000 per day in bareboat,” he says. “So if you ask me which business I want to be in, I know where I want to be.”

Understanding the value of a strategic asset is also key, and something people often fail to grasp.

On the upstream side for Golar, “Our strategic asset is that we know how to build Hilli, so then we can build it for BP as we are doing with No 2.”

He believes there is more mileage in Golar’s LNG carrier-to-FLNG conversion model. “I think we are five years ahead of anyone else, at least.”

But at some point there will be a switch to newbuildings, as there has been in the FSRU business.

Downstream, he refers to Golar Power’s Sergipe power plant play, and then he is back to the figures.

He prices an LNG cargo shipped to Brazil at $24m. If the regasified LNG is put through Golar’s plant, the wholesale price for selling the electricity is $48m over 17 days. “That is pure trading profit,” he says.

“This is what you pay for a cargo, this is what you are making, so effectively that cargo is worth $72m. The problem is, until that power station is up and running, you don’t have that access.”