Signatures made this week by 11 shipping bankers to commit their institutions to take carbon emissions into account when they finance ships is a landmark moment.

But does the initiative have the appetite or teeth to be truly impactful? And if not, should banks and other financiers aim to be more ambitious as evidence mounts of the growing global climate emergency?

With shipping remaining outside the Paris Agreement on climate change and no formal global policy yet implemented, the sector is seen by many environmental campaigners as lagging behind other industries in efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Taking control

But at least the banks — rarely the most radical of institutions on matters of social concern — have stepped up.

The Poseidon Principles initiative to cut the carbon intensity of their loan portfolios over time in line with the IMO’s proposed 50% reduction in emissions by 2050 shows the issue is bigger than something individual, independent shipowners can themselves control as some of them would wish.

As Star Bulk Carriers president Hamish Norton said of decarbonisation recently: “It’s not a shipowners’ problem yet. There are no mandates from regulators. It’s quite frankly nobody’s problem yet.”

He may think that, but clearly Citi, DNB, Societe Generale and eight other institutions — which hold about $100bn of the estimated $450bn total shipping loan book — think differently.

The signatory banks have shown by their action that they are willing to take steps to incentivise carbon cuts even if many owners, such as Star Bulk, remain as yet reluctant to invest in low-emission ships amid weak markets and an absence of regulatory compulsion.

Yet, however well-intentioned the banks’ collective new policy is, will it be effective? Is it enough to do more than nudge marginal reductions in carbon emissions?

Yet, however well-intentioned the banks’ collective new policy is, will it be effective? Is it enough to do more than nudge marginal reductions in carbon emissions?

Devil in the detail

The concept is clear, although it demands some explanation and further reading.

First the banks will build their baseline. They will ask owners of ships they finance to provide the emissions figures they now have to provide under the IMO data collection system.

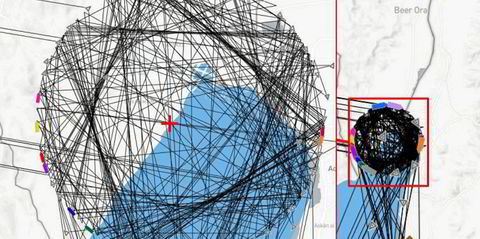

From that, each institution will calculate the carbon intensity of their portfolio — that is the grams of CO2 emitted per tonne notionally shipped each nautical mile.

From those figures, banks will be able to assess the relative alignment with the IMO proposal that the industry should cut emissions by 50% by 2050.

Each year that alignment target figure will reduce in line with the IMO's proposed trajectory, so the banks have pledged to drive their loan books down in the same direction. As a result, each bank will have an incentive to finance vessels with lower carbon intensity than those exiting the fleet.

As with most things in life, and pretty much everything in shipping, however, the devil will be in the detail.

The initial mostly European and Nordic signatories have pledged to keep the principles aligned to the IMO’s policies as those evolve in the coming years. For example, 2023 is set to be a pivotal moment when firm targets are put in place. The banks are also free to go above and beyond the collective framework if they see fit.

Further as some sceptics have already pointed out, there will be ample opportunity to game the system if desired. The carbon intensity of a VLCC is a small fraction of most other vessels largely due to the efficiencies of scale.

A cynical banker wanting to flatter his or her figures — and perhaps win a performance-related bonus — could theoretically finance a couple of VLCCs rather than the fleet of relatively efficient small containerships to nudge their metrics in the right direction.

Political momentum

And beyond that, there is the inherent gross contradiction that financing a VLCC built to carry crude oil could be considered in any way "green" regardless of its design and fuelling.

Let’s not forget that the history of the last 20 years has not shown bankers to have the highest ethical standards, worse perhaps even than journalists.

A more serious concern is that by focusing on carbon intensity, the banks involved have simply not been ambitious enough. Even though the decision by IMO member states last year to target a 50% cut was seen by some as radically ambitious, in the year since then it has started to look distinctly inadequate.

To win greater confidence, the banks should have also agreed to publish the absolute carbon emissions of their financed fleets. That would have given an even stronger signal to the market and the wider world.

Evidence is confronting us every day that climate change is real and happening fast with shocking consequences. Despite that, the political momentum towards global action has weakened.

Statement of intent

However, the public mood appears ahead of their representatives. And, ironically, so are investors and financial institutions, who see the inherent huge business risks in climate change.

It is in that context, that the Poseidon Principles initiative is a stunning piece of work pulled together by the chairman of the drafting committee, Citi’s Michael Parker, as one of the ideas that has grown out the Global Maritime Forum.

It has not been missed that Citi is the only US bank so far involved, with JP Morgan among those as yet on the sidelines. Perhaps it was Parker’s seemingly effortless tact and eloquence that talked his board into the idea. After all, if he hadn’t been a banker he should have been a professional diplomat. With DNB's Kristin Holth and Societe Generale's Paul Taylor, they make a powerful trio.

As a statement of intent, the Poseidon Principles will send a strong positive signal. However, history is likely to judge it only a modest start to what will be a revolution for the industry.