Pangaea Logistics Solutions often speaks at earnings time about its record of outperforming indices in the dry bulk sector.

According to a report by the Danish founders of a dry cargo index, the Rhode Island-based shipowner certainly does that — and by a good measure.

New York-listed Pangaea outperformed 21 other public dry bulk owners with a massive 38% premium to Baltic Exchange dry indices over 2018, according to the first VesselIndex Performance Report issued by Anders Liengaard and Soren Roschmann.

This equates to an average $3,889 per day over the indices for Pangaea’s fleet of nine panamaxes and 10 supramaxes operating last year — well ahead of second-placed Belships, which had a 22% premium at $2,497 above the indices for its supramaxes.

Six of the best

Liengaard & Roschmann’s list of the top six owners was rounded out by Thoresen Thai Agencies (17.5% and $1,724), New York and Oslo-listed Golden Ocean Group (15.1% and $2,171), India’s Great Eastern Shipping (14.5% and $1,664) and Hong Kong-listed Pacific Basin Shipping (10.1% and $972).

Roschmann will not publicly disclose the full rankings because it counts on industry customers to buy the report.

However, he reveals that the poorest performers were a pair of New York-listed Greek shipowners: George Economou’s DryShips, with a 12.8% underperformance and $1,823 per day behind the indices, and Seanergy Maritime Holdings (12.4% underperformance and $1,856 below indices).

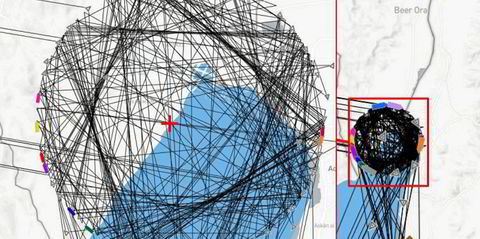

Liengaard and Roschmann are two former J Lauritzen executives who have established VesselIndex to try to standardise measures of performance across the handysize, supramax, panamax and capesize sectors.

Roschmann says it does not seek to explain why companies outperform or underperform their indices. It leaves that up to the owners.

Rather, it takes the earnings they report and aligns them with the vessels in their fleets to arrive at an “apples to apples” comparison across companies.

Baltic benchmark

For example, Roschmann says the benchmark for the Baltic handysize index is a 28,000-dwt bulker. But handysizes range from 22,000 dwt to 45,000 dwt, so which vessels a company actually operates is important.

“What if you’re operating 38,000-dwt vessels?” he asks. “The income potential should be 20% greater than the market vessel.

“So when you are hearing that companies are beating or underperforming the index, it’s interesting to know more about their vessels. If someone claims a 15% beat but the potential is 20% over the index, that’s a different story.”

A third-party independent view with regard to actual fleet composition should be useful to the market, he argues. “We think it’s extremely interesting for the companies themselves, but also for the stock analysts and others based on different sizes and mixes of vessels,” he says. “We know it’s difficult for analysts to figure out what is top and what is bottom with the various ship types. It’s confusing.”

So what does bring Pangaea out on top? Chief executive Ed Coll is succinct in his description.

“It is a simple story,” he says. “We do added-value business that flows down to the bottom line, including ice-class trade, stevedoring, projects and difficult cargoes.”

As TradeWinds has reported, the bulker operator has repeatedly shown a willingness to get its hands dirty with the cargo end of the business — whether that means hauling iron ore from remote Baffin Island in northern Canada or bauxite from Jamaica, or even taking over a terminal operation, as it has in Charleston, South Carolina.

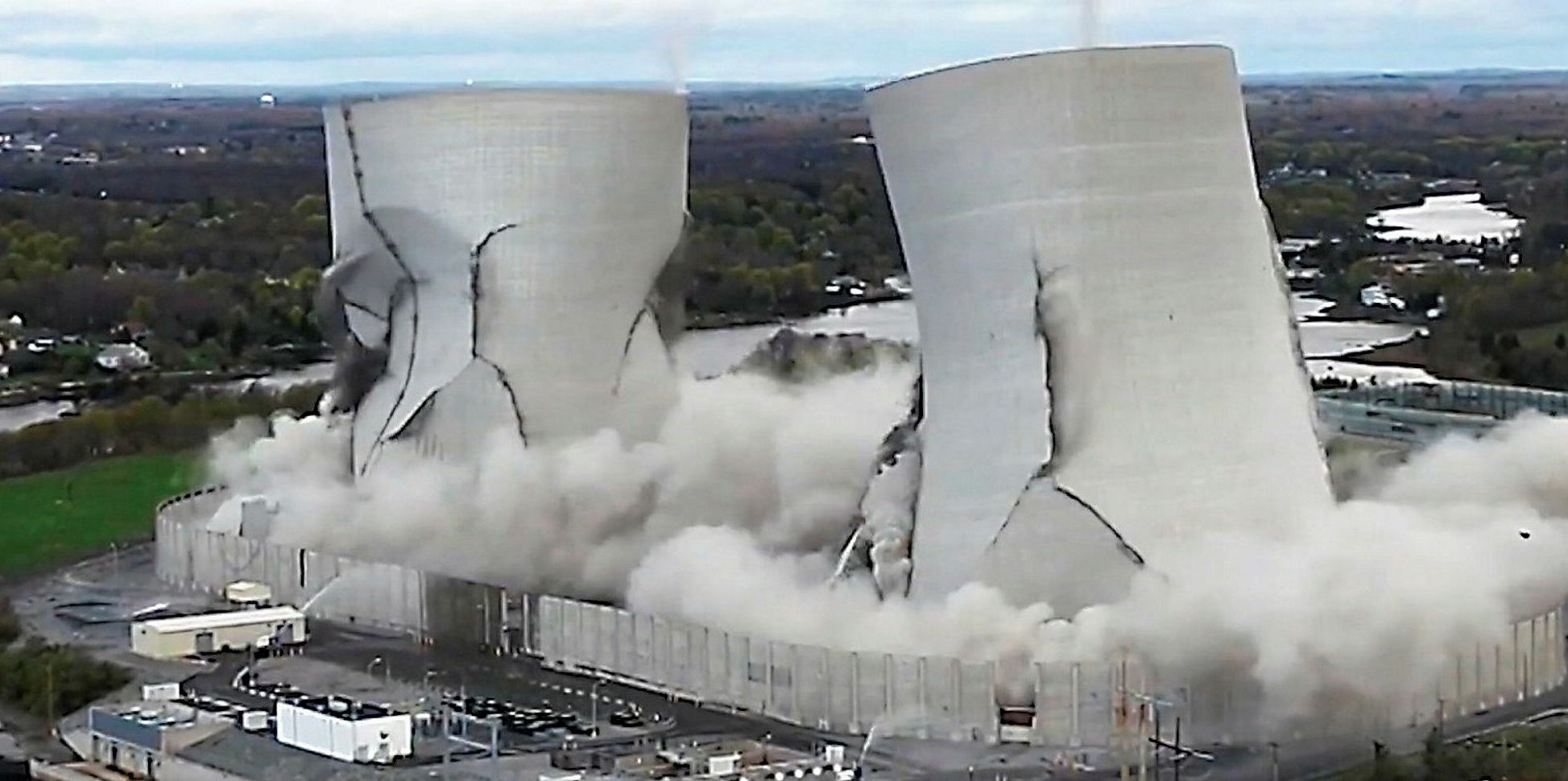

Demolition job

In April, it emerged that Pangaea was working with a partner on a 20-year contract managing a port in Massachusetts that required the implosion of two 500-foot (152-metre) cooling towers, breaking the Guinness World Record for the tallest ever demolished. The site is being developed for a combination of traditional bulk commodities and a “laydown” area for windfarm projects.

Coll was a little more descriptive of his company’s strategy at the time: “It all comes back to supporting our core business. The reason we’re able to outperform the markets continually is that we’re doing this sort of work.

“The freight market goes up and down, and it’s always great when it’s up. But we don’t get damaged when the market is poor because of these other businesses. These are the type of ventures that add long-term value to the company.”