Hold on for dear life, shipping markets could undergo big disruption in the years ahead.

That was the message from the global head of research at Simpson Spence Young at the TradeWinds Shipowners Forum in Oslo on Wednesday.

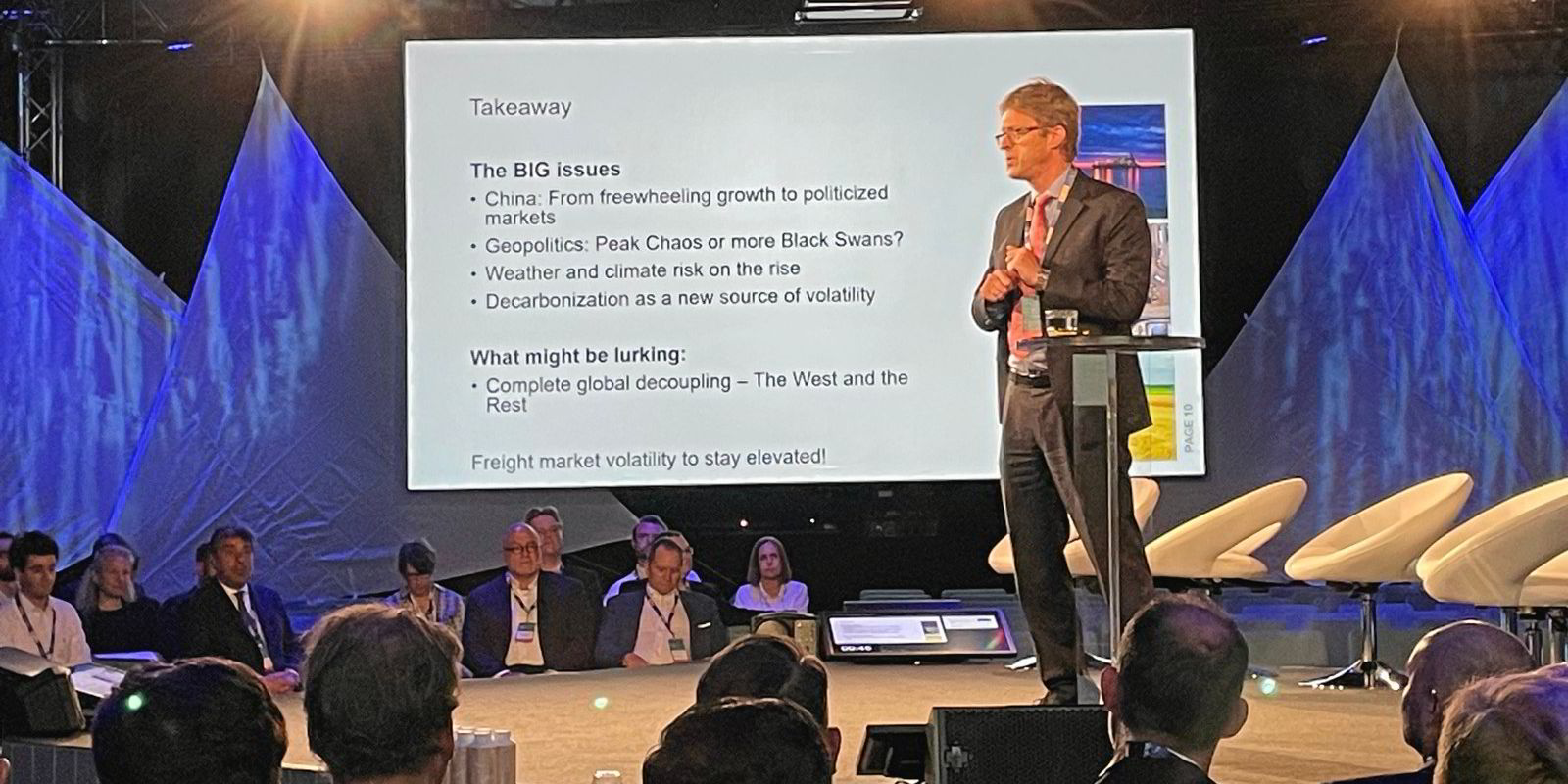

Lower economic growth in China, decarbonisation, changing weather patterns and the risk of division in global trading blocs are all among the factors that will make shipping markets all the more volatile in the future, Roar Adland told the conference.

“I do think there is a danger that we see a continued decoupling of the world into the West and the rest [of the world], both politically and economically,” he said.

“For shipping, the question is: How do you even deal with a situation where your trading partners and almost all of the largest commodity exporting and importing nations are within one geopolitical bloc — and not yours? How would it affect our ambitions and the speed of transition with regard to decarbonisation?

“I think there’s a risk that if this trend continues, we’re no longer going to talk about the ‘shadow fleet’. It will simply be known as THE fleet.”

Low Chinese economic growth will cause shorter, sharper cycles in shipping markets going forward because the country will be able to take advantage of its dominance in commodity markets and increasingly act as a price-sensitive buyer, buying when goods are cheap, he said.

“I would expect a more stop-and-go approach to commodity demand,” Adland said.

“The impact on shipping will be exacerbated by the restocking and destocking effects as well, so I would expect shorter, sharper cycles than in the past.”

Adland thinks that an end is in sight for freight premiums generated in inefficient markets disrupted by geopolitical issues in the past years.

Global trade and shipping markets have a remarkable ability to adapt to disruption and, in the absence of new shocks to the system, cargoes will tend to find a way to flow as efficiently as possible, he said.

“If we are at peak chaos, that geopolitical premium will gradually ebb away. That is especially so if commodity markets become less tight at the same time, reducing arbitrage opportunities,” he said.

What could add renewed disruption to shipping markets in the next 12 months is the switch from the La Nina weather system to El Nino, according to Adland.

He expects the effects to be “generally bullish” for shipping.

Higher temperatures and less rain in Asia are likely to increase the imports of agricultural products and coal, while drier conditions in Brazil and Australia will increase the availability of seaborne coal and iron ore.

Logistical constraints could crop up at chokepoints around the world, such as in the rivers of South America and the Panama Canal, creating a more inefficient market and more long-haul shipping.

Broader global efforts to decarbonise — especially in China — will affect shipping and make markets more volatile, Adland said.

The rapid build-out of solar and wind power in China and worldwide means fossil fuels are increasingly relegated to on-demand power production, he said.

This will create a much stronger link between the weather, seasonality and coal and gas demand than seen in the past, Adland told the conference.

Great sensitivity to weather will also add to stop-and-go demand for commodities and, therefore, more seasonality and volatility, he added.

And Adland expects zero-carbon marine fuels to create higher freight market volatility too because they will cost up to three times more than conventional fuels.

A two-tier market would be needed to avoid any effect on freight rates, with one tier comprised of charterers willing to pay the extra fuel costs — “which is possible but certainly not how shipping has ever worked” — or else a global carbon tax would be required to close the price gap, Adland said.

“If the freight market remains a single, free and perfectly competitive market, with an insufficiently high carbon tax, then not only will freight market volatility increase simply because the least cost-efficient vessels set the rate — but traditional fossil-fuelled ships will become substantially more profitable,” he said.

“That is probably not what we want.”