Fuel cells have long promised a potential to provide shipping with a clean source of electric power, but the twin challenges of system size and sourcing primary fuels have hampered uptake.

However, developments are afoot to take them to the next level.

Interest in fuel cells has gone up and down over the past few years, booming in 2018 but fading in 2019 as preparation for the switch to low-sulphur fuels took precedence; emerging again this year only to be cut-off by the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the promise of zero emissions and high-efficiency energy production is culminating in developments set to be led in the ferry and cruise sectors with the installation of fuel cell systems to handle vessels’ hotel loads as a forerunner to propulsion.

Fresh start

Swiss technology giant ABB is working with established fuel-cell developer Ballard Power Systems, which has built systems for buses, railways and trucks, to launch a 3MW marine unit the size of a 40-foot container this autumn.

“The next natural step for fuel cells is to cover auxiliary and port loads, and we are working on scaling up to megawatt-scale fuel-cell systems,” Jostein Bogen, global products manager for energy storage and fuel cells at ABB Marine & Ports, said.

“Shortsea shipping is driving environmental goals and working as a test bed for deepsea shipping,” Bogen added in advance of the launch.

But there is still a debate over the basic fuel-cell technology that determines what fuel will be used by them. Hydrogen is the obvious choice as the only emission is water, but is not yet realistic as a source of electricity for shipping. Other possibilities are methanol, ammonia, natural gas or LNG.

“Before you select fuel-cell technology, you need to address what kind of fuel you will have for primary use. That is the driver,” Jan-Erik Rasanen, head of new technology at Finnish ship design and engineering company Foreship, said.

ABB and Ballard are going for low-temperature proton-exchange or polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) fuel cells, which are relatively lightweight and so a good fit for buses but still too large, when including fuel tanks, for cars.

Rasanen said decisions on technology have to be a compromise depending on use.

But he added: “We have the opinion that solid oxide fuel cells are the future. They have higher efficiency, market share in land-based applications, and can use natural gas as a primary fuel.”

Solid oxide fuel cells have been used in power stations for many years, such as high-temperature PEM cells, but are larger than the low-temperature PEM types.

However, low-temperature PEM cells need very pure hydrogen, necessitating cleaning units that also take space, Rasanen said, and have an average electrical efficiency of 45% to 48%, while solid oxide cells can reach 60%.

Efficiency measures

Fuel cells have a high efficiency rate compared with conventional engines, said ABB’s Bogen, who cites flat efficiency curves of 60% at lowest loads down to 50% at maximum load. Ships’ engines are often operated at partial loads, he notes.

“The most efficient way of using hydrogen is directly in a fuel cell,” Bogen said. "Going forward, we see hydrogen as a very important energy carrier either to be used directly as a fuel on board or as a basis to produce other carbon-neutral synthetic fuels."

Rasanen said hydrogen would be the best fit if not for the space and bunkering issues due to its low energy density. He admitted that natural gas is a good starting point as an interim solution due to the availability of bunkering infrastructure and the IGF Code, although it will not achieve targeted long-term carbon cuts.

“I don’t believe a customer would add a fuel type for fuel cells just to provide the 'hotel load',” he said.

LNG has a similar carbon footprint to natural gas, but it is future-proofed as chemical processes are used in fuel cells, so there is not the methane slip associated with combustion.

Ammonia and methanol also have potential, but both need to be produced from renewable energy to hit emission targets.

Ballard and ABB are working on type approval of their 3MW FC Wave model with DNV GL, the Norwegian flag and fjord ferry operator Norled. It is expected to be on sale by late 2021.

Bogen said first users will be small vessels, tugs and coastal ferries often equipped with hybrid diesel power plants, followed by shortsea ships using hybrid battery and fuel cell systems.

Rasanen agreed that 2MW to 3MW installations on commuter ferries using compressed hydrogen are realistic within five years.

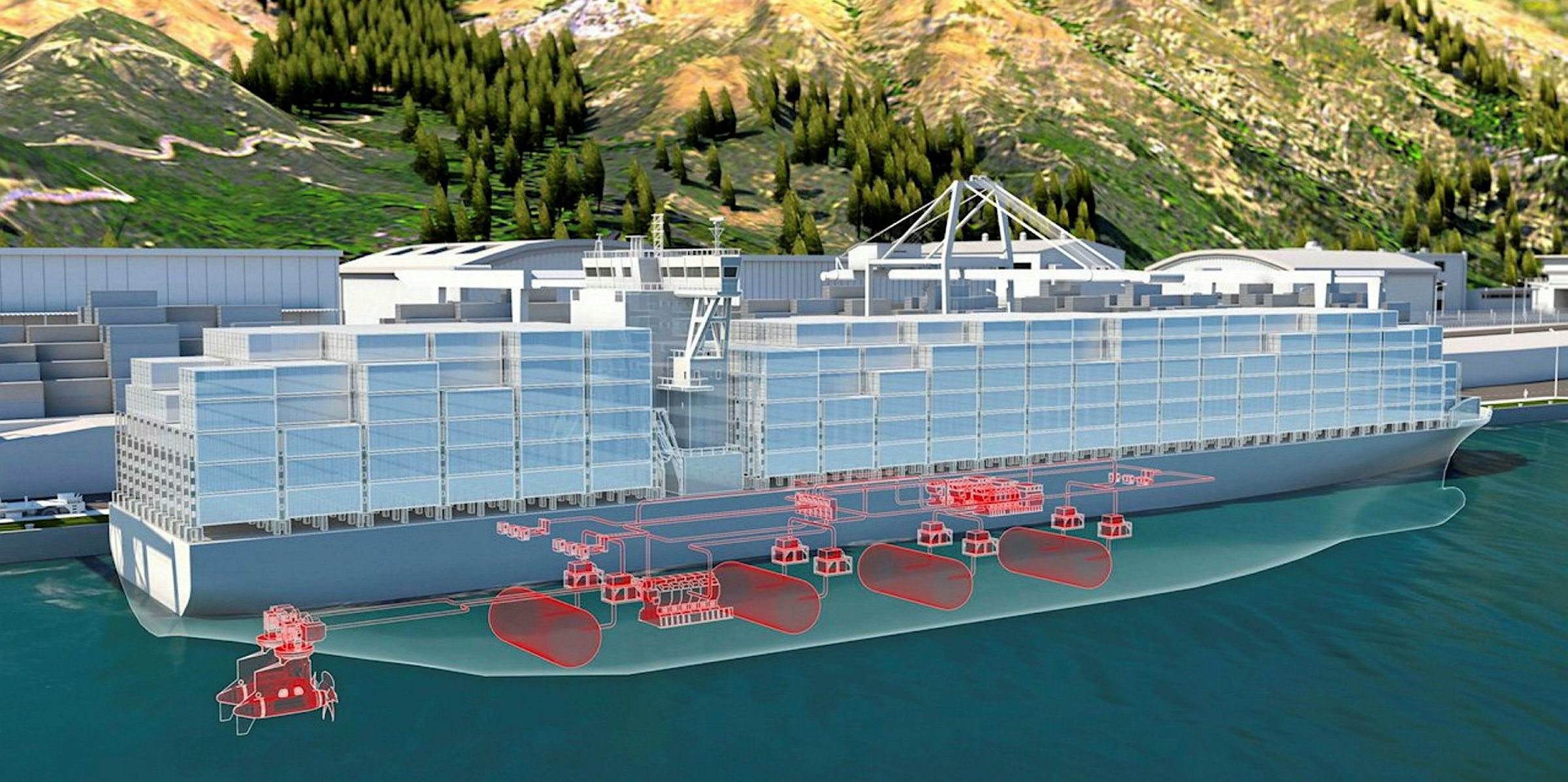

In July, Samsung Heavy Industries declared an intention to one day fit all newbuildings with fuel cells to meet decarbonisation targets as it announced a deal with New York-listed Bloom Energy to design and develop such vessels. But that day has not yet been specified.