The alarming increase in the frequency and scale of containership fires should come as no surprise considering the rapid expansion of the boxship business in recent years, according to statistics from the International Union of Marine Insurance (IUMI).

The headline grabbing fires that have rung up in excess of $1bn in losses for hull and cargo underwriters in the past decade are directly related to the increasing scale of the business, the marine insurance union’s figures suggest.

In 2000, containership capacity amounted to 4.4m teu. Today, it stands at 20m teu. In 2000, the average vessel was 1,000 teu in size, compared with 5,000 teu today.

Growth in teu capacity

IUMI believes that growth is directly linked to the high number of cargo-related fires and claims being registered.

Its figures show that between 2000 and 2015 there were 56 containership fires, damaging 8,252 containers and costing insurers $1.03bn.

Between 2000 and 2019, hull insurers paid out $188.7m for hull claims related to containership fires.

IUMI’s policy committee chair Helle Hammer said as well as the cost to insurers the increasing size of the containership industry is posing an increasing safety and environmental threat.

“The expected growth in the containership fleet, and the larger average size of container vessels, will inevitably lead to a further danger to crew and the environment and increased costs of damage to cargo and vessels,” she said.

What can be done?

The big question for marine insurers is what can they do about it? The cause of the majority of fires is widely thought to be misdeclared cargo.

Cosco has said that the cause of a fire on the 10,000-teu Cosco Pacific (built 2008) was a misdeclared cargo of lithium batteries, while a German accident report concluded the fire on the 7,150-teu Yantian Express (built 2002) was likely sparked by a misdeclared cargo of coconut charcoal.

Through the Cargo Incident Notification System carriers are now building a database of high-risk shippers and cargo types with a record of misdeclaration.

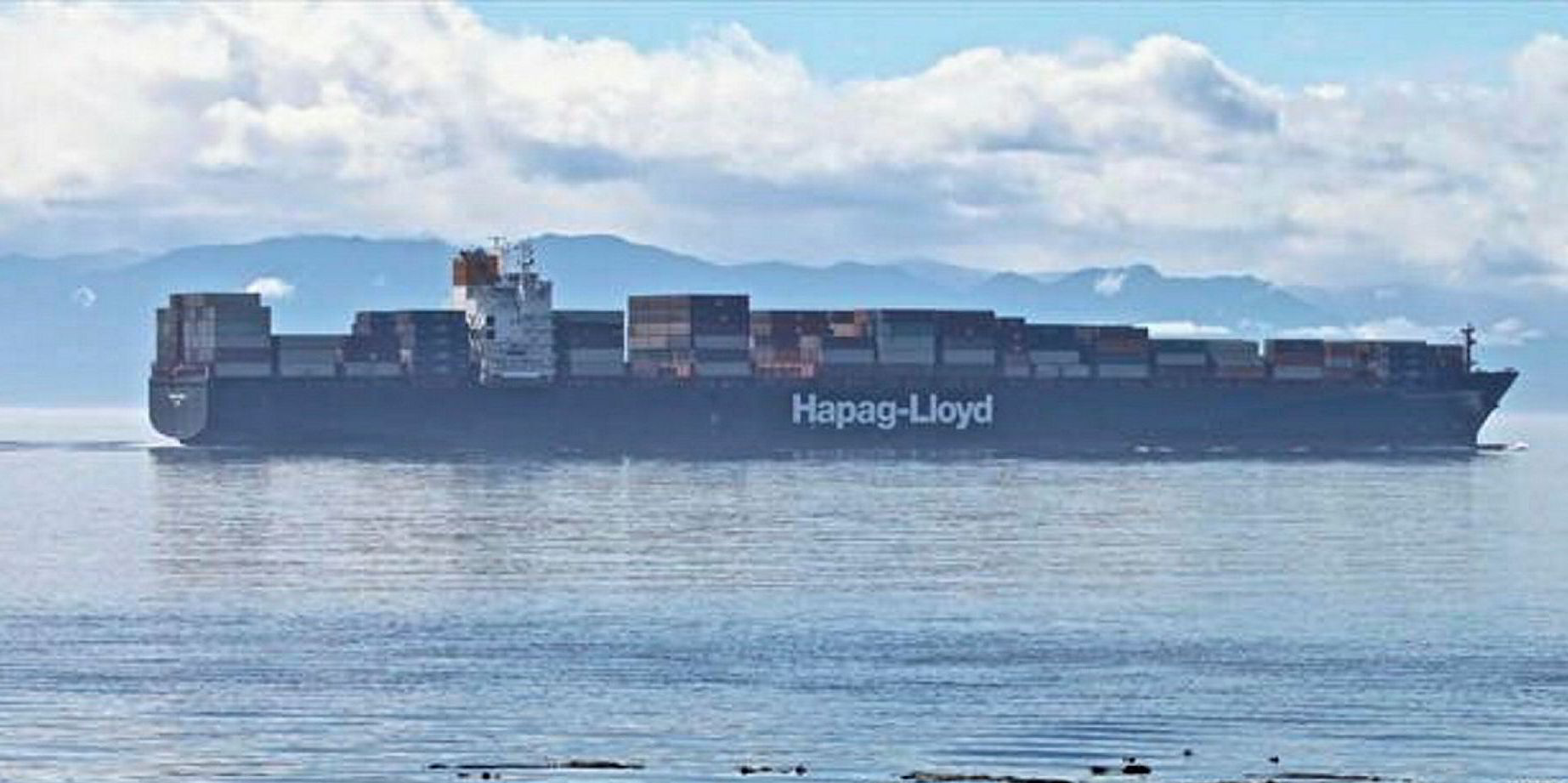

Some outfits, such as Hapag-Lloyd, have also threatened to fine shippers caught misdeclaring, although whether any fines have been issued has not been made clear.

Classification societies, such as ABS and Bureau Veritas, have also come up with guidelines for the stowage of dangerous goods.

Norwegian marine insurer Gard held a seminar of safety experts to try to come up with other safety measures to tackle the problem.

However, IUMI is putting its efforts into gathering expertise to come up with on board fire prevention and fire-control equipment that is appropriate for the modern generation of 20,000-teu mega-ships.

“Tackling misdeclaration is a key part of this but, having said that, containerised cargo is increasing and so is the risk. So we cannot just rely on risk prevention but must also look at fire fighting too,” Hammer said.

With the support of the German government, IUMI has been able to get a proposal on the table at the IMO for the upcoming Maritime Safety Committee meeting. Also backing the IMO move is the Bahamas flag state, shipowners' association Bimco and the Community of European Shipyards Association.

IUMI has not revealed what is in its proposals as it has yet to be released to other IMO member states.

Solas revisions

But Hammer said it involves seeking amendments to the fire safety requirements of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (Solas), which she believes is dated.

“It is clear that the current Solas regulations are not adequate in considering the size of the modern ultra-large containerships and very large containerships, and the complexities of fighting a fire aboard these vessels,” she said.

Another issue that has emerged from the German accident report into the fire on the Yantian Express is whether firefighting equipment on containerships is reliable.

The report highlighted how the ship’s CO2 extinguishing system did not activate in hold number one, due to a problem with its time-delay system.

In addition, the crew found it hard to tackle the fire with mist lances from underneath the container pads. Another issue was that firefighting water disabled electrical bilge pumps, creating a dangerous situation.