Norwegian cruise industry legend Knut Kloster died on Sunday at the age of 91.

Heralded as the father of modern mass-market cruising and giant cruiseships, he was also known for his devotion to humanitarian endeavours and the environment.

Right from his birth, shipping was always in Kloster's blood. For three generations, the Kloster family had been shipowners.

Kloster, who held a degree in marine engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, took the helm of Klosters Rederi at the age of 30 following the death of his father.

The company owned a small fleet of tankers and bulk carriers, but Kloster saw a new vision for it in the passenger trades.

In 1965, he introduced the world’s first cruise ferry, the 10,600-gt Sunward, which was designed to carry British tourists to Gibraltar and Spain. The ultra-modern ship had all the trappings and facilities of a cruiseship and featured a vehicle deck that could carry the passengers’ cars.

But Kloster's plan soon fell apart. UK currency restrictions and the closure of the Gibraltar-Spanish border by Spain's Francisco Franco Bahamonde government saw the route abandoned after only a few months.

This could have meant financial ruin for Kloster but in a shrewd move he teamed up with a Miami-based businessman, Ted Arison, who wanted to start a cruise line.

Together they created Norwegian Caribbean Line, using the Sunward on short cruises out of Miami. The Florida cruise fleet at the time consisted of worn-out former US coastal steamers. The arrival of the brand-new Sunward sent this rag-tag bunch off into well-deserved retirement.

The Sunward was an instant hit and Kloster went on to order even larger, more luxurious ships that were often referred to collectively as the White Fleet.

The cruise line's success also prompted three other Norwegian shipping families to band together and order a fleet of ultra-modern cruiseships for the mass market Caribbean cruise trade. The three owners operated the ships collectively under the name Royal Caribbean Cruises.

Kloster’s partnership with Arison eventually soured and the two parted company. Arison went on to form Carnival Cruise Lines, the largest cruise company in the world today.

Kloster held on to Norwegian. He was well known for his hands-on approach to his business, frequently sailing on his ships and listening first-hand to the concerns of his clients and crew.

A former Norwegian employee described Kloster as being a true gentleman, with a demeanour that put any of his underlings immediately at ease, and a willingness to let his employees try new ideas.

It was Bruce Nierenberg, then a junior manager at the company, who suggested the concept of developing a private island in the Bahamas for cruiseship calls. Kloster immediately gave him the go-ahead. Today, almost every Caribbean-based cruise line has at least one.

Nierenberg subsequently went on to start Premier Cruises and would later head up other cruise lines.

World’s first mega-cruiseship

By the late 1970s, Kloster believed it was time to move forward from the 20,000-gt cruiseships that were the backbone of the cruise industry then. He shocked the industry when he bought the giant French transatlantic liner France (built 1960) and announced he would be converting it into the world’s first giant cruiseship aimed at the mass market.

Hauled out of a six-year lay-up, and sent for extensive rebuilding in Germany, the France re-entered service as Norwegian’s 70,200-gt Norway in 1980. It was three times the size of almost any other ship operating in the Caribbean at the time.

There was no other ship on earth like it, and like its tiny predecessor Sunward, it was an instant hit with passengers and a cash cow for Norwegian.

Kloster’s competitors, who were initially aghast at his idea of introducing such a large ship, soon dropped their scepticism and began ordering similar-size ships.

Norwegian never joined in this building boom of mega-cruiseships that began in the 1980s.

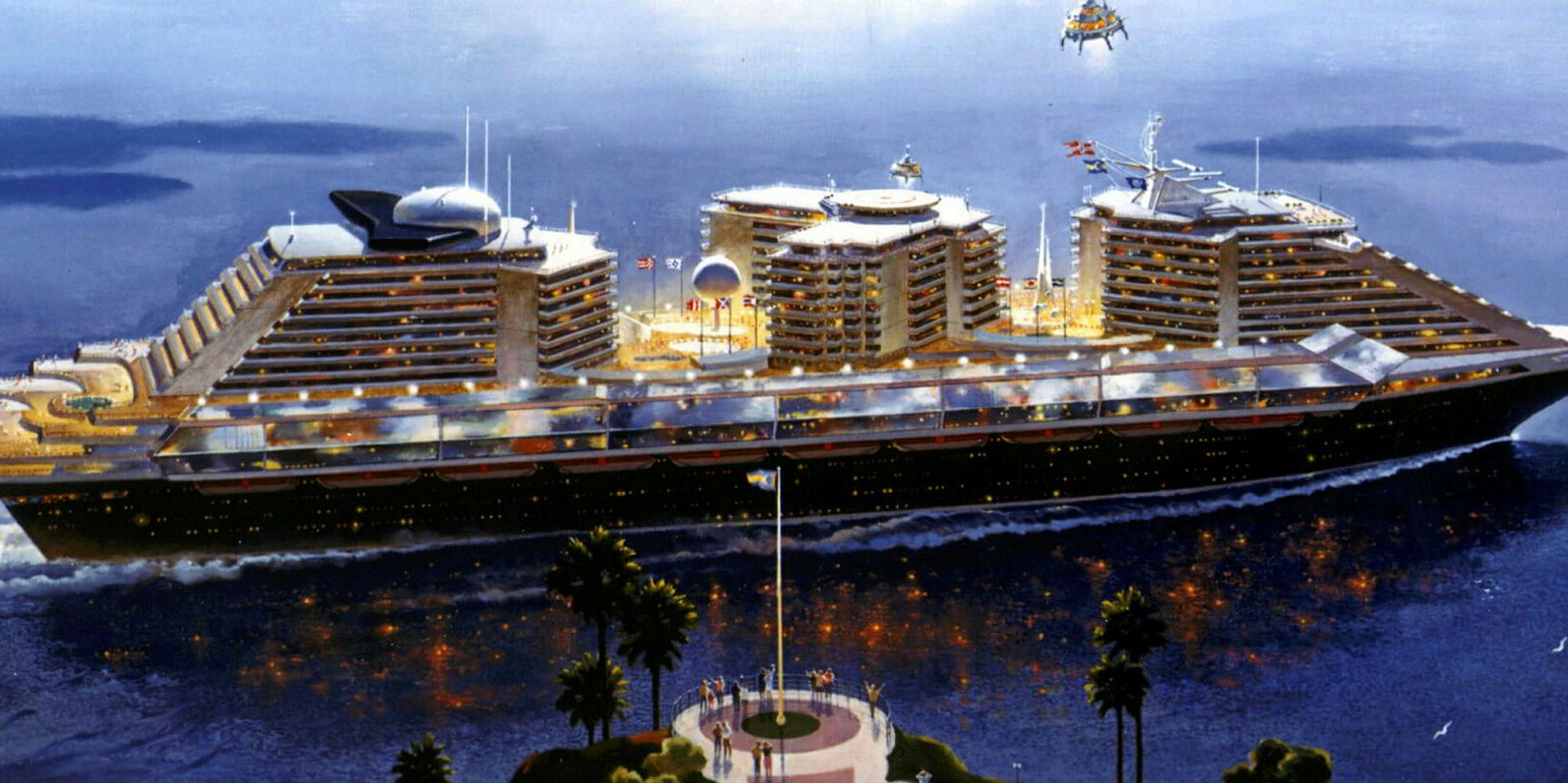

Kloster was instead focused on something far more ambitious — an unprecedented 250,000-gt cruiseship called Phoenix World City that would have carried over 5,000 passengers.

Kloster spent almost two decades trying to drum up interest in the billion-dollar project in the financial markets.

The Phoenix World City was never built, but many of the features and innovations that came out of the intensive and long-running development process were later incorporated into the new generation of modern cruise liners that began to appear in the 1990s.

With Kloster firmly focused on the project, his attention to Norwegian faded. At the turn of the millennium, the company was sold to Malaysia’s Genting Group.

Humanitarian and environmentalist

Industry insiders suggest that Kloster’s extensive contributions to humanitarian and environmental causes outweigh his contributions to the cruise industry.

While Kloster made public very few details of these activities, he was widely known for investing in socially responsible enterprises that valued all stakeholders.

Green technology

He insisted his ships were designed to provide a good working environment for crews, and featured trailblazing green technology long before the concept became vogue or an industry necessity.

He played a key role in developing a traditional Norwegian village for the 1994 Winter Olympics Games in Lillehammer, and he sponsored the 15,000-mile (24,140 km) journey of the replica Viking ship Gaia, which delivered thousands of messages from children to world leaders in Rio de Janeiro at the 1992 Earth Summit.