Livestock carriers get a bad rap due to valid safety and animal welfare concerns. And the sustainability of shipping live animals thousands of miles is likely to come under increasing scrutiny.

But it doesn’t have to be this way, according to the two top-tier players in this niche sector.

Senior executives at Dutch shipowner Vroon’s Livestock Express and Australia’s Wellard believe that livestock can be transported safely and humanely by sea in a sustainable manner, but only with modern, purpose-built ships operated under a strict global regulatory framework.

Unfortunately, this operating environment does not exist today.

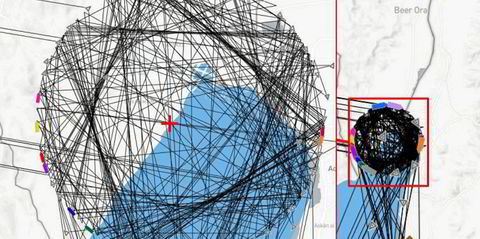

Figures supplied to TW+ by Maritime Strategies International paint a poor picture of the global livestock carrier fleet.

There are just over 170 livestock carriers worldwide, and none on order. The fleet is spread widely between a large number of small owners, most with between one and three ships.

The fleet’s average age stands at 36 years — 16 years more than the 20-year average for the global merchant shipping fleet. More than 75% of livestock carriers are above the 30-year mark.

Only about 20% of the fleet was originally designed to carry livestock. The rest are conversions of older vessels nearing the end of their useful lives as cargo ships. Former ro-ros and feeder boxships are the most common types for such repurposing.

An expose by the UK’s Guardian newspaper last year found that livestock carriers are twice as likely to suffer a total loss from sinking or grounding as the rest of the commercial fleet.

According to the paper’s analysis, which estimated the global live export trade at nearly $22.2bn, seven livestock carriers were lost between January 2010 and September 2020, representing 4.7% of the fleet.

Some observers have claimed that converted livestock carriers are not suited to their new role, especially in terms of stability and structural integrity.

Animal rights activists say these ships are often crudely converted, with poor ventilation systems and overcrowded pens, leading to high mortality rates among the animals in transit.

However, Paul Pistorius, managing director of Livestock Express, and Wellard chairman John Klepec argue that it is wrong to treat livestock shipping as a homogenous fleet, when in fact the opposite is true.

Both companies operate modern, purpose-built livestock carriers that are regarded as the best in the industry in terms of safety and the welfare of their four-legged passengers.

“The biggest threat to the global live export industry is old ships,” Klepec tells TW+.

“They have inferior standards and livestock services, and they are more prone to accidents and breakdowns. Those ships give a bad name to a legitimate industry, which can operate to high animal welfare standards and perform a valuable role in helping feed the world.”

Klepec would like to see a worldwide 25-year age limit imposed on all livestock carriers.

“Unfortunately, older ships are over-represented in the number of ships lost, a situation that we cannot have when they are carrying the most sensitive of cargoes,” he says.

Although not privy to the accident investigation reports, Pistorius suspects the loss of stability in recent livestock carrier casualties was probably attributable to overloading, poor design and improper management — or a combination of these factors.

“Compromises need to be made when converting a vessel, and this is the reason we opt for newbuilds as opposed to conversions, although it must be said that not all conversions are poor and/or have any issues with stability,” he says.

Enhanced regulation

Klepec and Pistorius say that although new, purpose-built livestock carriers are the way forward, a comprehensive international regulatory framework covering the way the ships are designed, built and operated is a necessity for any meaningful change.

“At present, international livestock shipping is largely unregulated, to the detriment of the industry’s reputation and the livestock on board inferior vessels,” Klepec explains.

Pistorius says the regulations that need to be adhered to in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, the US and Ireland should be mandatory across the globe.

“This would ensure that only good-quality, properly designed ships with sufficient redundancy, manned by experienced and competent crew assisted by well-trained stockmen and veterinarians, would be eligible to trade,” he says.

“The IMO needs to step up,” Klepec adds. “At a minimum, it should incorporate a version of Australia’s livestock vessel regulations into international shipping regulations. It is troubling that when older vessels cannot meet Australia’s standards, they are simply transferred to another route where those regulations do not apply.”

This loophole that allows substandard livestock carriers to shift to less regulated trades also worries Pistorius, who laments New Zealand’s decision to stop all livestock exports within the next two years.

“Unfortunately, all that will happen is that an alternative supply country will be found, most likely where little or no regulation concerning live exports will be in force, resulting in animals being overloaded onto vessels not complying with the greatest animal welfare standards,” he says.

Necessary trade

Animal activists have often called for a ban on the transport of livestock by sea.

But the trade plays an integral role in various countries’ food safety and security, making it highly unlikely that such a ban will ever come into effect.

Countries supplying the trade have excess production, whereas importing countries have a range of needs, including a domestic herd/flock size incapable of meeting demand; religious requirements such as in-country halal or kosher slaughter; the lack of a cold supply chain to accommodate chilled or frozen imports; and the need to increase the national breeding herd.

The world livestock trade consists principally of sheep and cattle.

With cattle, the trade for herd rebuilding involves mainly high-value breeding or dairy cattle imported to improve the genetic pool and/or milk production.

The slaughter/fattening of feeder cattle is often based on countries that have not enough arable land to support large herds, or insufficient domestic cattle to meet demand, or alternatively have large quantities of cheap feed that can be used to fatten cattle at prices lower than can be achieved in the exporting countries. Animals are “lofted” (kept in pens and fattened up) for 90-360 days to increase their weight before consumption.

The sheep for slaughter trade largely involves older animals from the wool farming industry that are exported to the Middle East, where they are processed relatively quickly on arrival for almost immediate consumption.

Safe, humane transport

Livestock Express is involved mainly in the highly regulated trades where animal welfare concerns and the quality of tonnage are regulated, according to Pistorius.

It exited the dedicated sheep trade many years ago and its most recent vessels are designed principally for the carriage of cattle.

Wellard’s three ships operate in both the sheep and cattle trades.

Although each company still operates one livestock carrier converted from a ro-ro, the rest are purpose-built. Both claim their vessels were designed to meet all animal welfare standards.

“In the 1990s, Wellard started designing purpose-built livestock carriers to obtain a quantum leap improvement from the keel up, to set new standards through superior feed, water, ventilation, dynamic stability and high cruising speed,” Klepec says.

Livestock Express’ recent newbuildings are entirely enclosed, which Pistorius says “allows us to control the environment but also protects the livestock from external weather elements” and prevents water entering the decks in rough weather.

Ventilation systems, incorporated at the design stage, allow direct jetting of fresh air to each pen and the removal of stale air.

“No compromises are made on livestock services such as drainage, which is essential to allow washdowns and clean decks as necessary,” says Pistorius.

Automatic water and food delivery systems with segregated fodder silos to prevent cross-contamination, as well as advanced coatings and enhanced maintenance programmes to address corrosion problems caused by acidic urine, are also features of both companies’ ships.

Well-trained onboard management is essential. “There’s no point investing in modern shipping tonnage if there isn’t a skilled crew operating the vessel and caring for the livestock,” Klepec says.

Livestock Express and Wellard are working on their visions for the next generation of livestock carriers, stressing a need to further improve the welfare of animals and for ships be more environmentally sustainable.

“We are at this moment very much involved in researching this very question,” Pistorius says.

Klepec adds: “Our vision for the future is one of continuous improvement, learning from our past experience and introducing new technologies and improved designs.”

Both companies are looking at new technologies that will improve the welfare of the animals, such as, in Livestock Express’ case, equipment that will allow automatic monitoring of the behaviour and condition of each individual animal or group.

They also believe that increasing the redundancy of mission-critical equipment is essential to de-risk operations, guarantee crew and animal welfare, mitigate disruption in case of failures, or avoid disruption altogether.

And, like most other shipowners, they are improving the sustainability of their vessels through silicon underwater hull paints, plus advanced weather- and engine-monitoring systems.

Also under serious consideration is the possibility of using alternative fuels, although according to Klepec, at the moment there is no clear path.

The livestock carriers of the future the two men describe are a world away from the old, converted ships that make up the majority of the current fleet. And that, they say, is the way the trade needs to go.