Uneven application of the International Maritime Organization’s carbon rules puts container feeder ships at a disadvantage to vessels that can do the same job without having to comply with the regulations, a senior Contships Management executive says.

Managers at the world’s largest independent owner of container feeder ships have noticed that major charterers are starting to ship boxes on heavylift multipurpose vessels (, which are exempt from thenew Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII).

“In the two weeks since the regulation started, we’ve already seen two such ships being hired and replacing feeder container ships,” Contships chief operating officer Angelos Tyrogalas told TradeWinds.

He expects the phenomenon to acquire even bigger proportions, as dozens of other vessels are going through the motions to register as potentially CII-exempt heavylift MPPs.

The IMO regulation, which entered into force on 1 January, lists “heavy-load carriers” in a catalogue of special vessels to which the CII does not apply.

According to subsequent guidance from the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS), heavylift MPPs can fall into that category — subject, among other factors, to endorsement by the flag administration.

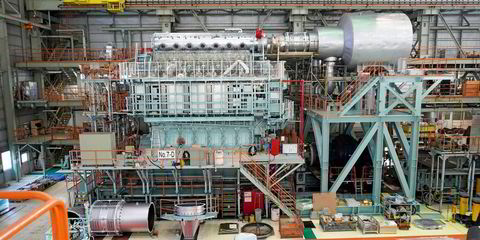

Tyrogalas argues that carrying containers on heavylift vessels might be environmentally counterproductive, as they require higher-consumption engines for propulsion.

Furthermore, he said their cranes and cargo hold arrangements can require more time for loading and discharging, leading to longer port calls and a higher carbon output per box carried under CII rules.

The CII formula, which ranks vessels according to their carbon footprint and whittles out the worst performers over time, has drawn criticism for possible unintended, competition-distorting effects.

The situation described by Contships could be the first real-life example of such distortions.

The company, which manages 46 feeder ships built between 2003 and 2016 with a capacity from 750 teu to 1,432 teu, said its vessels are unfairly penalised by the regulation.

Not only did the company see the IMO turn down calls to exclude shorthaul feeders from the regulation, it now says it sees the heavylift exemption potentially creating an additional “unfair imbalance”, to its detriment.

“This must be addressed now — not in 2026, when the CII is planned to be revised,” Tyrogalas said.

“If heavylift ships are excluded, then Contships believes that feeders up to 1,500 teu must follow, taking into consideration the uniqueness of their trading.”

As an alternative, he said “right correction factors” for container feedering must be introduced.

Work hand-in-hand

The CII grades vessels from A to E, assigning a mark based on operational performance after dividing annual emissions by vessel capacity and then multiplying that quotient by distance travelled.

Vessels rating D for three consecutive years or E for a single year must provide a corrective action plan, failing which it could be banned from trading.

Due to the nature of their shorthaul trade that involves short distances, as well as frequent and long port calls, feeder container ships are at a natural disadvantage.

Contships feeders make usually about 5,000 port calls per year, on average five times more than larger boxships.

“It is unfair to penalise feeder container ships as they are the first and last marine mile in the global supply chain — transporting containers from hub ports to smaller regional ports and vice-versa, carrying vital cargo to smaller communities,” Tyrogalas said.

Then there is the role of charterers.

Based on last year’s figures, Contships has identical sisterships that can rate from B to E, just depending on their speed and the ports charterers instruct them to visit.

“The essential part is to work together with charterers, who must accept their share of addressing the CII regulation,” Tyrogalas said.

Bimco, the only organisation uniting all kinds of maritime stakeholders, last year provided a blueprint as to how such a cooperation could look like.

However, the new CII time charter clause it worked out has met with major charterers’ disapproval.

A group of such companies, including Mediterranean Shipping Co, AP Moller-Maersk, CMA CGM and Hapag-Lloyd, called the clause as “imbalanced and unworkable”.

However, rejecting the Bimco clause and apparently seeking to exploit loopholes in the existing CII rulebook may leave charterers’ other environmental initiatives appear in a bad light.

“We believe that owners and charterers alike must ... come to terms with the reality of the CII regulations and cooperate to ensure a smooth transition,” Tyrogalas said.