Bimco’s long-awaited time-charter clause to deal with the new Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) is finally out. But the agonising has hardly begun, not to mention the arbitrating.

Some of the best charter-drafting heads in the shipping industry have been huddled in Bimco documentary committee meetings most of this year trying to bring contractual order into regulatory chaos.

The rest of the best heads are ducking comment.

“I’m afraid we don’t have anything intelligent to say yet,” said the head of the relevant department of one leading organisation that was represented on the drafting committee.

Likewise, a regulatory specialist at a top law firm is eager to talk to TradeWinds about the subject. Just not yet.

“As you can imagine, [we] are presently advising many clients on various aspects of the new clause, which makes it impossible for me to discuss this with the press at this point,” the expert said. Certainly not until “the dust has settled”.

Bimco’s documentary committee should not be blamed if it has failed to sort the commercial jumble that was created by a poorly conceived and heavy-handed approach to decarbonisation.

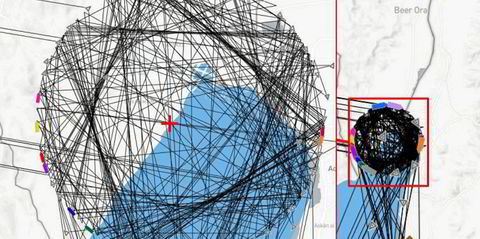

The most dreaded of decarbonisation regulations soon coming into force — CII — attempts to grade the emissions of all the different kinds of vessels in the oceangoing fleet, along a single scale of “carbon intensity” that lumps physical performance together with trading history.

The CII has been criticised for its apples-divided-by-oranges approach to measuring vessels’ carbon intensity and for the unintended consequences that will result when owners game the formula. There is no doubt that the International Maritime Organization will tinker with CII after its introduction on 1 January, and again after sharp-toothed enforcement begins a year later.

But its more fundamental and harder-to-patch-up problem is that it misconceives the way shipping business is done. It is basically irreconcilable with tramp chartering.

Some owners and operators will always have to charter ships to customers they will never see, introduced by brokers, with names even the brokers have to Google

Optimists, in particular the shipowners, charterers, insurers, and lawyers who drafted the Bimco clause, have underscored the need for charterers and owners to work together at achieving the IMO’s decarbonisation goals, and how their clause aims to give charterers a fair share of the burden.

They urge that the times demand a new and more cooperative approach to ship chartering.

The times cannot always get what they demand.

The idea of a cooperative owner-charterer relationship presupposes a relatively simple commercial situation in which two parties, or easily enumerable sets of parties, do business in an ongoing partnership, as a service provider and customer, and can if necessary accommodate each others’ needs for the sake of the relationship. And for the sake of the planet, of course.

That sounds like a description of industrial shipping, a somewhat idealised one, in which top commercial executives of high-profile stock-listed companies, such as Volkswagen and Hyundai, sit down with their opposite numbers at the leading car carrier owners — all this with their bankers and investors looking on — and come up with multi-year contracts with sustainable rates and operational practices that save the planet and, by the way, spare the owners’ CII ratings and the charterers’ environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) statistics.

But not all ship trading can be like that. Some owners and operators will always have to charter vessels to customers they will never see, introduced by brokers, with names even the brokers have to Google — not least, in order to fix opportunistic backhaul cargoes to avoid ballast legs. Ballasting, remember, is terrible for the environment. And such customers fix on price.

Stranger-in-the-night charterers

Spot chartering will always present challenges to “know your customer” regulatory demands.

And the behaviour of stranger-in-the-night charterers who are not long-term partners and who are less subject to ESG pressure will not typically be governed by enlightened self-interest. They will not fix on Bimco’s clause.

And without a patch like the Bimco clause, the new CII regulations must be seen as a new way of creating damage claims. The CII allows charterers to do invisible but quantifiable damage to ships they charter. A charterer’s orders can give a vessel a D rating, making it damaged goods as a trading and a saleable asset, no less than hull fouling or engine damage.

The inevitable result will be a massive volume of disputes of a brand-new kind, whether owners resist what charterers see as lawful orders, or follow orders and suffer the expensive regulatory consequences.

Everybody should lawyer up now.