The risk of nationalisation in many port projects and financings in emerging and frontier markets has usually been deemed to be somewhat academic. This changed with the nationalisation of Djibouti’s Doraleh Container Terminal.

Djibouti is in the Horn of Africa, at the gateway of the Suez Canal and near some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. Because of its strategic location, China set up a military base in Djibouti in 2017 to protect its growing interests abroad. The US, France, Italy and Japan also have a military presence there.

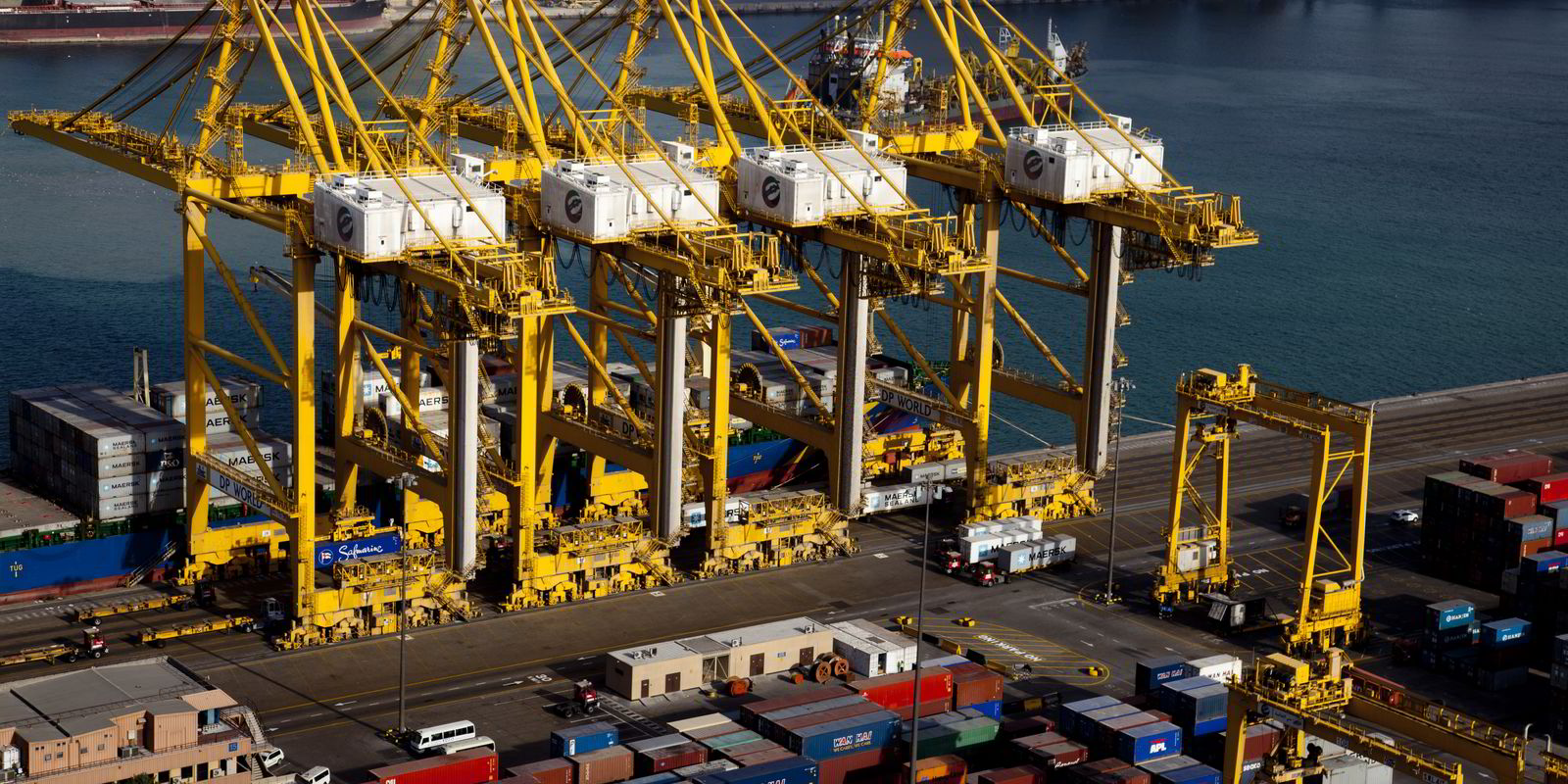

In 2018, Djibouti’s government terminated Dubai-based DP World’s 25-year concession and subsequently nationalised Doraleh.

Operation of Doraleh was offered to China Merchants Ports Holdings, which has since expanded the port with additional container facilities, as well as dry bulk and multipurpose terminals. There are ambitious plans for a $3.5bn free-trade zone and global logistics hub, turning Djibouti into a key link in China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The cancellation and nationalisation led to legal proceedings in the UK and in Hong Kong’s High Court, where DP World accused China Merchants of causing the Djibouti government to nationalise Doraleh.

A tribunal of the London Court of International Arbitration this month ordered Djibouti to hand back control of Doraleh to DP World within two months or pay damages. But does not mean DP World will be able to take back control of the facility or collect damages for its loss, which one expert estimated could exceed $1bn. Predictably, Djibouti has not accepted the ruling.

Operators, investors and financiers in port projects in emerging and frontier markets are already exposed to a wide variety of risks and challenges: geopolitics, security and terrorism, local content requirements, local licences and permits, compliance risk and natural hazards such as earthquakes and typhoons.

Unfortunately, the Doraleh dispute demonstrates that the risk of nationalisation is real and that companies operating in challenging markets face an elevated danger of contract cancellations and expropriation.

Protection against political risk

In addition to structuring their foreign direct investments in the port sector in a tax-efficient manner, seeking government assurances and obtaining political-risk insurance, companies often choose a structure that provides protection against political risk through investment treaty protections.

In port projects and acquisitions of terminals, companies should endeavour to structure the investment so that there is a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) between the investor’s home country and the country in which the investment is made.

Unfortunately, the Doraleh dispute demonstrates that the risk of nationalisation is real and that port operators, investors and financiers operating in challenging markets face an elevated danger of contract cancellations and expropriation

A BIT, essentially an agreement between two countries for the promotion and protection of private investments, typically offers some protection against nationalisation and expropriation. However, it is important to bear in mind that every BIT is different, as it is a negotiated agreement between two countries.

Some reports state that there are more than 2,500 BITs in force. Most of them provide for compensation in the event of expropriation or nationalisation and typically allow a foreign investor to sue a country directly by submitting a claim to arbitration (often to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, part of the World Bank Group) rather than suing the host country in its own courts.

With the heightened awareness of nationalisation risks, BITs will become increasingly important to help companies fell comfortable on projects.

The port sector provides robust opportunities for infrastructure investment in emerging and frontier markets, particularly for investors, operators and financiers focusing on gateway volume over transshipment traffic. Each project and transaction offers its own opportunities and challenges, and there are no magic bullets.

It is difficult to see how the nationalisation of Doraleh could have been avoided or how it can be reversed, but with appropriate legal structuring, some risks can be navigated and mitigated so that bankable and profitable port projects can be executed.

Ton van den Bosch is a partner and head of the Singapore office of law firm Addleshaw Goddard, where he advises on corporate transactions and project development in the energy, offshore, logistics, ports and terminals sectors in emerging markets in Africa, the Gulf and Asia