It would be easy to think that the mega-merger of China’s largest state shipbuilders, which was officially approved in recent days, was driven by difficult market conditions.

The combination of the two shipyard groups has been in the works for months amid a raft of problems connected with the Trump trade war, slowing global economic growth and maritime regulatory issues having stifled orders.

The number of ships booked in the first nine months of 2019 was 43% lower than during the same period last year, according to Clarksons Research. Dozens of yards around the world have recently gone out of business.

The origins of the Far East corporate tie-up stretch at least a decade, to even before the global financial crisis began to bite.

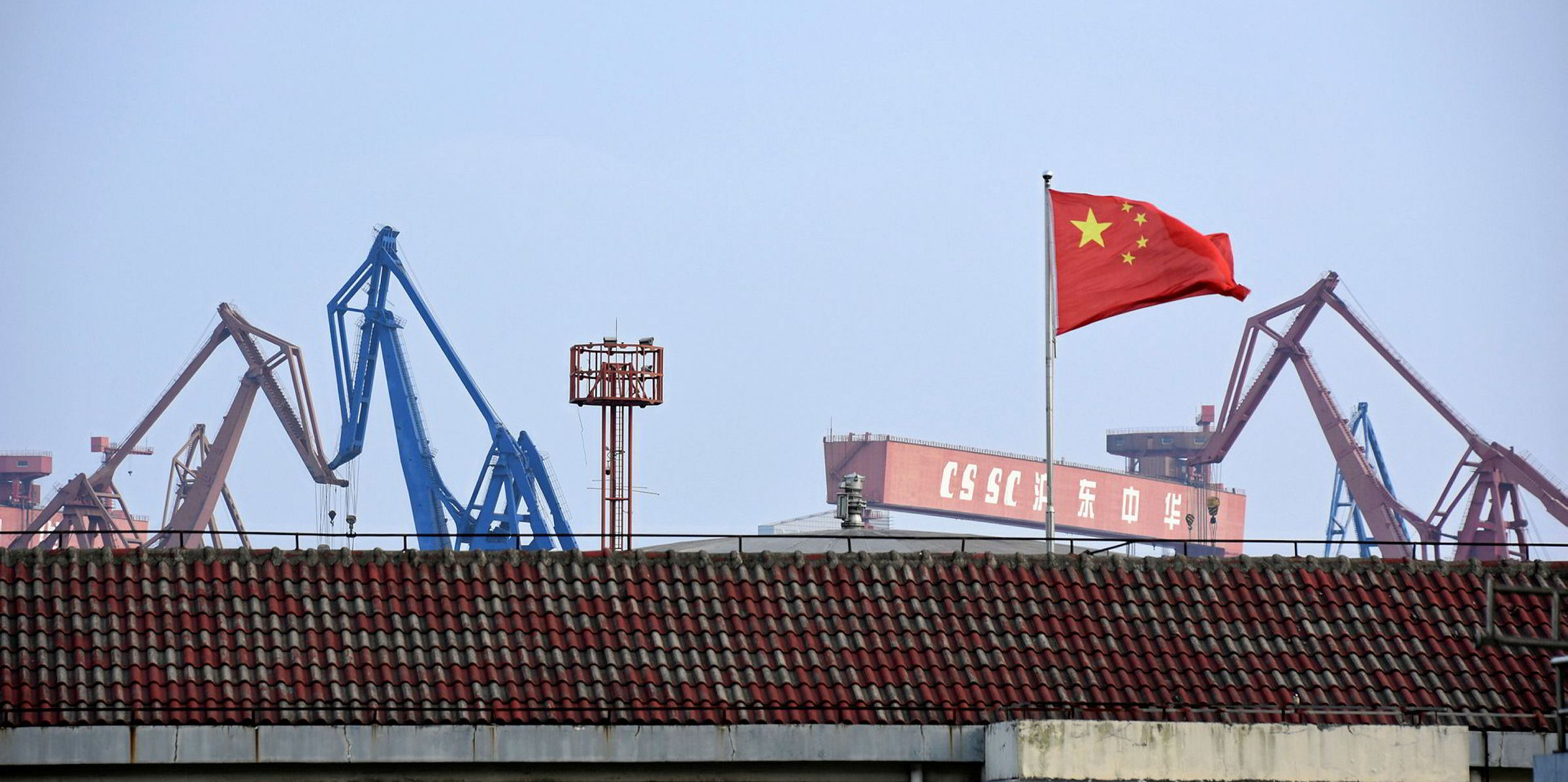

And the partnership between China State Shipbuilding Corp (CSSC) and China Shipbuilding Industry Corp (CSIC) is driven by a range of imperatives.

This is about politics as well as commerce. It is about military issues as well as civil ones and it is about expansion as well as consolidation.

Fruits of mixed economy

The merger follows a spate of similar moves in the Chinese shipowning and energy sectors as the Communist Party re-exerts its grip on the industry.

President Xi Jinping has appreciated the benefits to China of a mixed economy and becoming part of the global trading community.

But he also likes his party to be in control. And ambitious strategies, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), require detailed central planning.

This is about politics as well as commerce. It is about military issues as well as civil ones and it is about expansion as well as consolidation

Terry Macalister

There is a political and military dimension to what China is doing with the BRI, not least in the South China Sea where the navy is active securing territorial advantage.

CSSC and CSIC have constructed dozens of naval craft since they were separated from each other in 1999, including aircraft carriers, Type 055 destroyers and nuclear submarines.

The companies are looking for cost savings in this area through consolidation as budgets are squeezed by the nation’s own slower economic growth.

But they also want to grow from volume to value producer.

As Tan Naifen, deputy secretary general of the China Association of the National Shipbuilding Industry, put it: “It's time for capable Chinese shipyards to make complex, high value-added vessels to reach buyers in new segments, through asset restructure, international collaboration and research and development activities.”

Expanding the portfolio

China wants to move out of mass tanker and bulker production to lead in military vessels, LNG carriers, luxury cruise liners, mega-containerships and sophisticated offshore vessels.

As Zhou Lisha, a researcher at the Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, told China Daily, the Chinese vessel construction sector wants to become more intelligent, digitalised and environmentally friendly.

The forthcoming IMO 2020 fuel sulphur content rules and expected carbon regulations have caused shipowners to postpone new orders. But they also point to a future of new ships with low-carbon propulsion that all yards want to cash in on — if they have the know-how.

CSSC and CSIC have started to diversify the ship types they offer, but the ambition is to do this in a major way to challenge those high-value segments of the market dominated by South Korean, Japanese or European yards.

South Korea won more than 85% of LNG carrier orders last year and has made its own moves to consolidate its shipbuilding firepower by merging Hyundai Heavy Industries with DSME. Financial figures out this week from HHI suggest the shipbuilding arm of the combined business, Korea Shipbuilding & Offshore Engineering, is doing better after its partnership.

And the China merger, bringing together half the country’s entire industry in yard capacity terms, creates a worthy rival to the South Korean group.

As my Shanghai-based colleague, Bob Rust, put it in a perceptive analysis 18 months ago: “Tighter political control, more aggressive state-owned conglomerates and investment strategies in tune with foreign policy are the new shape of the Chinese business landscape following the most recent public rounds of Communist Party and state policymaking.”

Party demands

Along with this, China has opposed tougher demands on private and foreign-owned firms operating in the country, requiring them to submit key board decisions to internal party officials for review.

More political control can get in the way of pure commercial moneymaking and bigger does not always mean better in terms of competitiveness and cost savings.

But make no mistake, a powerful new force has just been born in shipbuilding and its impact will be felt around the globe.