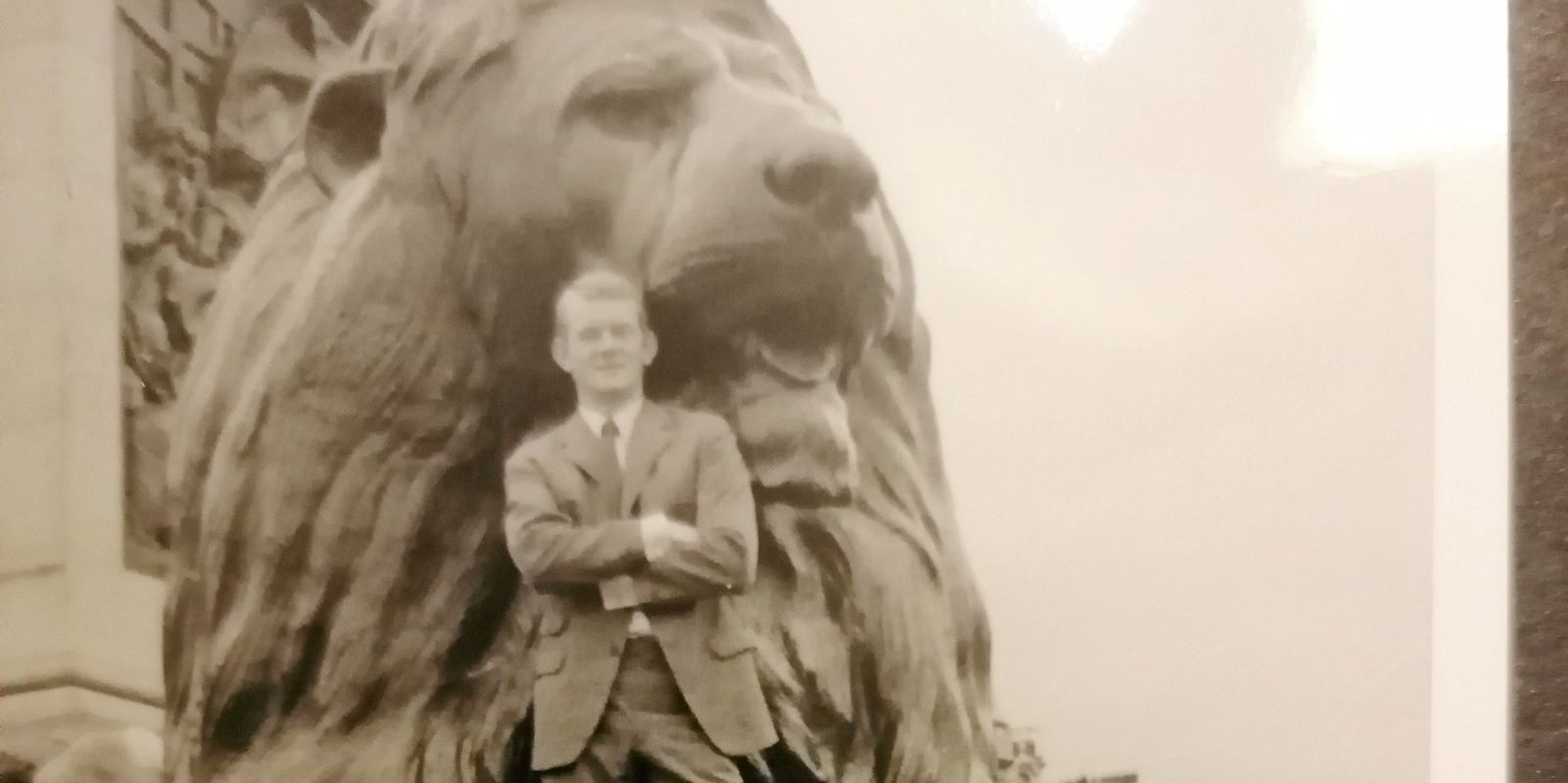

After qualifying as a ship manager, Ulfar Norddahl was sent to Liverpool where he met his wife-to-be and learnt about shipbroking with Roberts Shipping.

Later he worked as a broker in Germany with Grammerstorf Kiel, Teutonia Fracht and Assekuranz Kontor Hamburg, but his career as a ship’s chandler began in the Railway Inn in Runcorn, UK, when a former captain of British military intelligence who had worked with the Danish Resistance during World War II spoke to Norddahl in Danish.

“I had just got married to my English fiance, trainee nurse Susan, after being engaged for two years," he said. "Anyway, the ship’s chandler offered me a job and I started working for him the next week.

“With my shipbroking experience it was an easy job, contacting shipowners and visiting them all over Europe, speaking languages I knew.”

Ships were met on arrival at all hours, day and night, and many captains had responsibility to purchase all provisions and stores themselves. Norddahl competed in Liverpool with two Norwegian chandlers and another Dane.

“I was the youngest and like to think the quickest to get around,” he said. “One time a captain could not make up his mind when I was on board with the two Norwegians. I said: ‘Why not give me the order so not to make the two Norwegians upset?’ He agreed.

“Another time I was trying to get through the door to a captain’s cabin, and was wedged next to the old Norwegian. The captain asked us to hold out our business cards and the one that reached furthest would get the orders. My arm was longer!”

Ships often sailed as soon as stores were delivered, and the bill paid or signed for.

“One time the ship sailed, and I had to be winched over the side with one foot in the hook at the end of the wire onto the end of the pier as the vessel left the port. This is unthinkable now but, in those days, everything was possible.”

“Many times, when a captain said he had no requirements, I would say: ‘Is it possible to have a cup of coffee?’ Most often, after 10 minutes of conversation, he would give me his orders for the next voyage — sometimes only a few hundred pounds worth but other times many thousands.”

Vessels had much larger crews and less refrigeration, so they needed more fresh produce.

“We once had a big order from a bulk carrier for more than one ton of meat," he said. "It was decided to put several pallets of meat on a refrigerated lorry and keep it running until room was made in the freezers. But the meat was left on the lorry when the ship sailed for Canada.

“The master sent a message the next day that he didn’t have any meat! We ‘told’ him not to worry, we would order it for him in Canada. But his port was in a remote outpost for grain loading only accessible by helicopter at enormous cost.

“OK then the next port. But it was Algeria. We had to give up. It was a very bad day.”