Private ownership is an advantage in a challenging market, two leading privately owned shipmanagers claim.

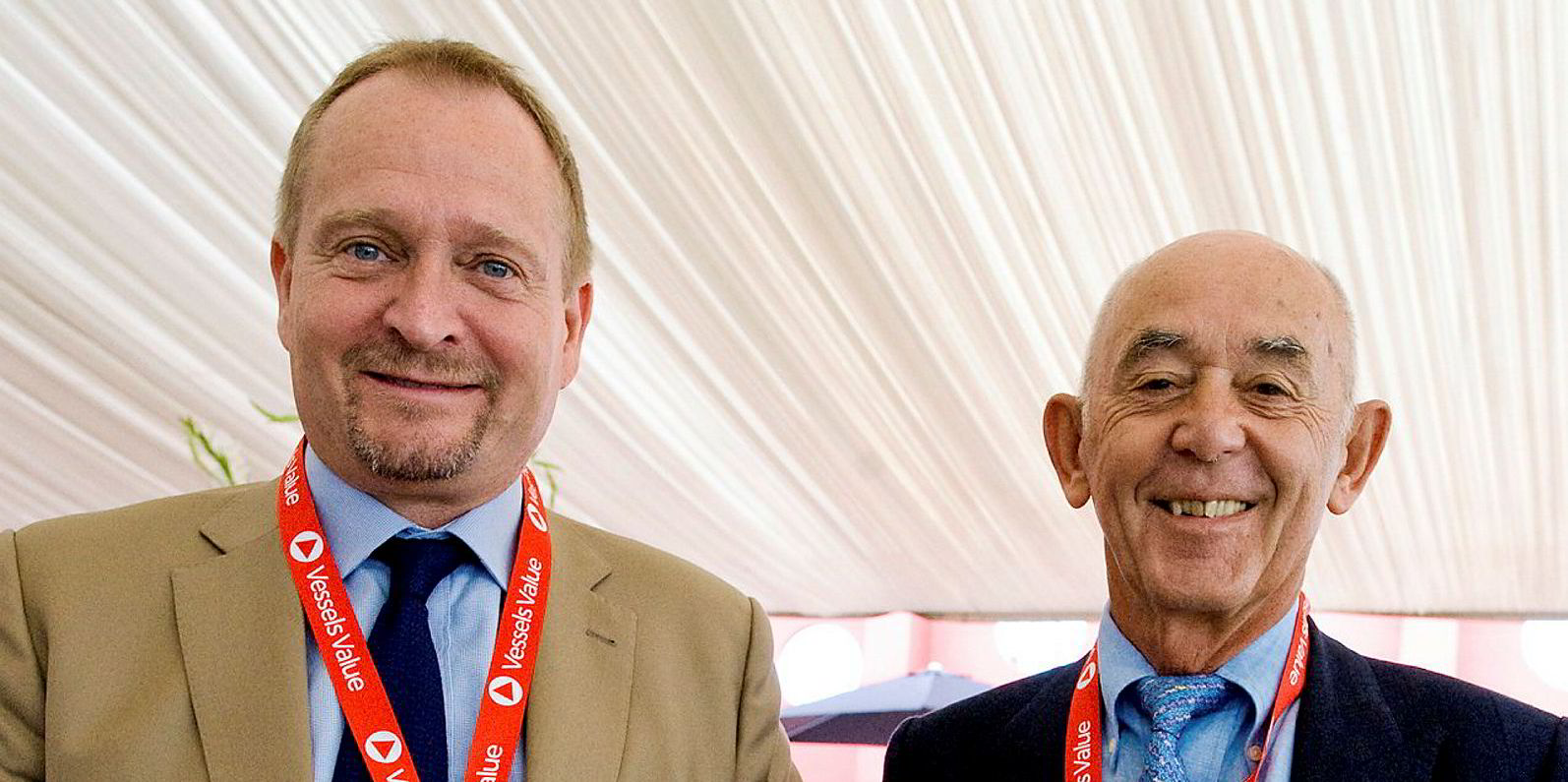

The heads of Hong Kong's two biggest managers, Anglo-Eastern's Bjorn Hojgaard and Fleet Management's Kishore Rajvanshy, believe private ownership offers greater flexibility than their publicly owned rivals.

They say it allows them to grow at a rate that fits the market rather than the expectations of private investors, leaving them in a position to turn down customers that do not fit their shipmanagement philosophy.

Globally, Anglo-Eastern is the leading shipmanager by the number of ships under full technical management, according to port state control (PSC) database Equasis. While Fleet, owned by Harry Banga's Caravel Group, is in third position.

Carl Schou, chief executive of publicly owned Wilhelmsen Ship Management admitted private ownership with greater flexibility and freedom from the burden of quarterly reporting could have benefits.

"Seen from that perspective, I could be tempted to agree," he said in a recent interview in Shanghai. But he believes the stringent requirements of reporting and compliance required of a public company can also be beneficial to customers.

As the shipmanagement unit of shipping and logistics group Wilh Wilhelmsen ASA, Schou said his company also has owners who understand his business from the inside.

"As part of a large group we don't have to deliver 15% growth per year by ourselves," he said.

Like that of its competitors, Fleet's growth has been modest of late.

"Last year, we said goodbye to 80 ships and took in 90," says managing director Rajvanshy. "Ships were demolished, ships were sold — just natural churn."

'We decline them all the time'

As Fleet celebrates its 25th anniversary this year, Rajvanshy is keen to point out that the company offers only full technical management, has the best record in the industry for detentions per PSC inspection according to Equasis, and unlike its closest competitors, its growth has been exclusively organic.

Fleet was originally to be an in-house manager for the fleet of Noble Group, but became a third-party manager when the Noble incarnation of the 1990s decided against owning ships.

Rajvanshy has kept the bell of Fleet's first ship, the 65,700-dwt bulker Min Noble (built 1981), as a reminder. The vessel was scrapped in 2011 as the Xin Feng.

Many of Fleet's first external clients were Scandinavian and Japanese outfits, which still account for more than 100 of Fleet's vessels.

One misstep, Rajvanshy concedes, was that he signed on LPG shipowner Varun Shipping. When creditors arrested eight Varun VLGCs that Fleet was managing, it cost the manager more than $4m in crew wages alone. Fleet eventually recouped 70% to 80% of its losses through legal action, he says, but is still out of pocket $1m to $1.5m.

"The important thing for people like us is that we are not interested in every customer that comes along," he says. "We decline owners who are not in line with our way of thinking — our core values about safety and crew welfare. We decline them all the time."

He says it is not difficult to discern if a potential client will fit with Fleet's philosophy.

You have to be able to say no to shipowners whose interests are not aligned with yours. If you choose to work with the right clients, it will make you a better company

Bjorn Hojgaard

"It becomes apparent when discussing potential new projects with a company," Rajvanshy says. "Especially in discussions over the budgeted operating cost."

Anglo-Eastern chief executive Hojgaard agrees.

"You have to be able to say no to shipowners whose interests are not aligned with yours," he says. He views shipmanagement as "a partnership business, not a transactional business".

"If you choose to work with the right clients, it will make you a better company."

With some 650 ships under full technical management, Anglo-Eastern's fleet growth has been flat in the last year and a half, Hojgaard says.

Anglo-Eastern seeks growth through its customers' newbuildings and acquisitions, rather than aggressively recruiting customers.

"We get new business from new clients from time to time, but on the other hand we can lose business when clients get acquired," he says, citing last year's Global Ship Lease merger with Poseidon Containers as an example.

Private company, private books

With shipping industry players as owners, Anglo-Eastern does not feel pressure to grow for growth's sake.

"Growth is important because it helps offset inflationary pressures and it creates opportunities for our people," he says. "But it's not what I lose sleep over.

"As chief executive of a privately held company with shareholders who are taking the long view and who are positive on the industry, it's fantastic to be able to work on meaningful goals and not short-term profits or growth."

Sources say Anglo-Eastern's owners today include Glasgow-based J&J Denholm, with the largest single shareholding, Montreal's Fednav and a management group.

Former shareholder Bocimar sold out in 2015 before the merger of Anglo-Eastern and Hojgaard's former employer Univan.

Hojgaard admits that Anglo-Eastern's margin is "probably not the highest in the industry", without putting that in numbers. "We're a private company with private books," he says.

He is optimistic for the long term because shipowners need to band together to meet technological and regulatory challenges.

"I think overall that third-party shipmanagement has got a positive future because of the fact you can pool resources with those of like-minded owners in a single unit that gives you breadth and depth," Hojgaard says.

This story is part of a business focus on shipmanagement. For the full report, read next Friday's print edition.