Sweden’s Concordia Maritime halted its ambitious project to convert a product tanker into a feeder vessel because it was 12 months late tapping into the boxship boom, its chief executive has told TradeWinds.

Erik Lewenhaupt, who was appointed chief executive in November last year, said global economic uncertainty and the bulging orderbook for container ships made the technically feasible plans financially unworkable.

Armed with new technical information from the project, he said the ideas could still be employed to convert tankers into specialist ships employed in sectors such as heavylift or wind farm construction.

Lewenhaupt, a former head of sustainability at Stena Line, had seen ferries working beyond 40 years, while the average age of tankers scrapped in 2021 was around 23 years.

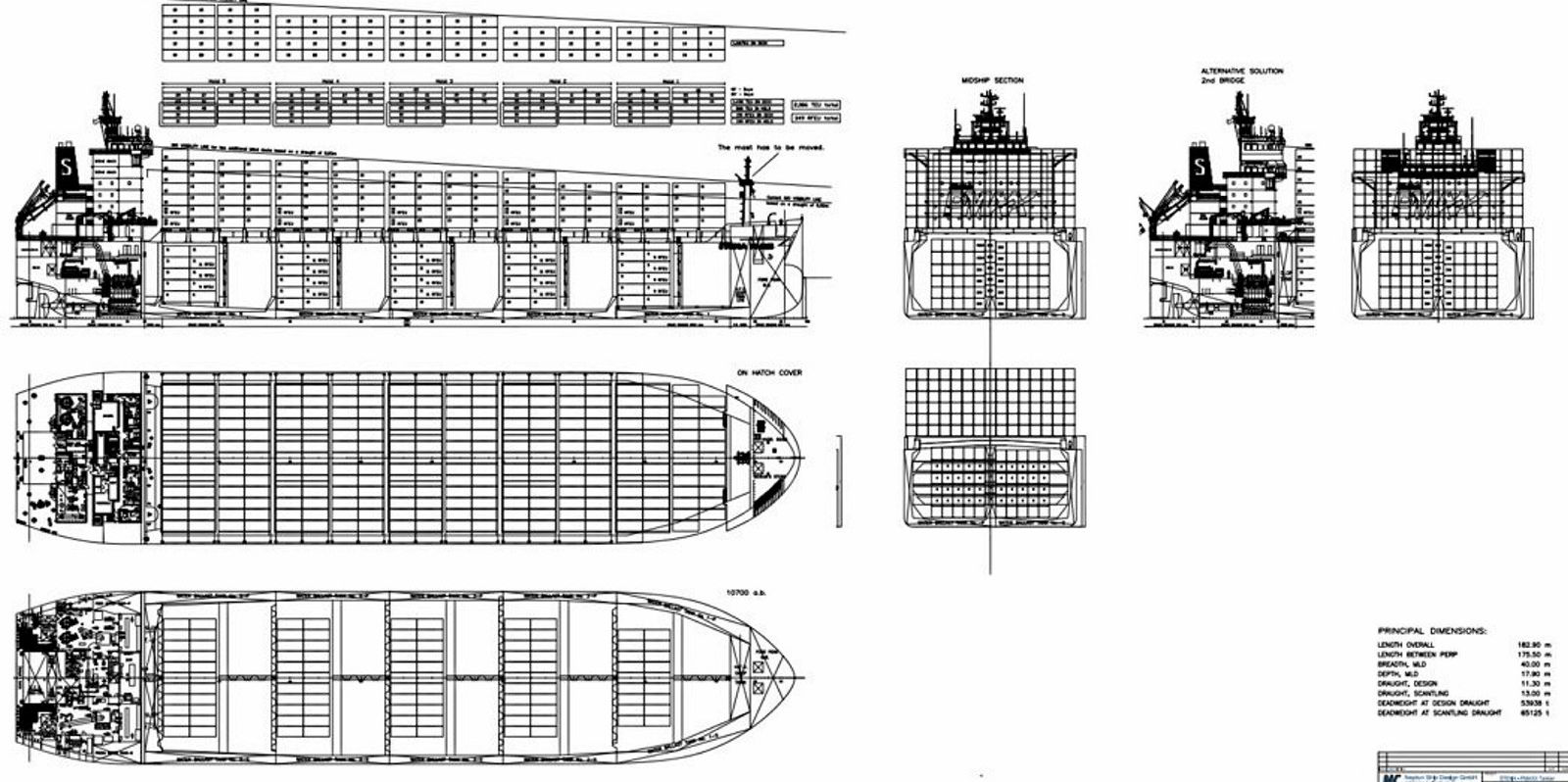

Late last year, Concordia identified the potential to extend the lifespan of one of its seven 65,200-dwt P-Max ships into a 2,100-teu feeder. It analysed the market, assessed that there was still demand, and worked on the designs with Neptun Ship Design of Germany and Sweden’s Stena Teknik.

Stena Teknik has been previously involved in conversions and a project to extend the length of ro-ros compared with basic designs.

A little late

“They gave us the thumbs up,” Lewenhaupt said. “So we’re confident that it can be done, but we should have been 12 months earlier, really.

“That was our mistake. But we tried, we turned every stone, and this was a good idea, it was just a little late.”

He said they could have had a feeder vessel ready in 12 months and is certain it would have generated a deal in 2021.

But he said many boxship owners are now more hesitant about striking deals owing to economic conditions and the state of the orderbook.

While product tankers of more than 10,000 dwt have an orderbook of less than 6% of the overall fleet, the container ship orderbook stands at more than 30%.

The container ship market has boomed in the past couple of years owing to Covid-driven supply-chain disruption, but cooled in recent months with rising inflation and other economic woes affecting consumer demand.

The Concordia conversion would have included removing the ship’s deck to turn it into a fully converted container ship.

The P-Max vessels were seen as particularly suitable because they are wider and shallower than regular MRs, Lewenhaupt said.

“For us, it’s been trying to find hidden values in the ships due to their dimensions,” he said. “If they were regular specification tankers, I think someone else who is more clever than we are would have probably done so already.

“But for us, when the market has been in the doldrums in the past, what else can we do to increase value from these ships?

“What we learned is that you can do a lot of things with a ship as long as the base quality is there.”

The project is not a new concept. The first container ship, the Ideal X, sailed in 1956 after being converted from a World War II tanker. Bulkers were also pressed into carrying containers during the liner boom.

But previous conversions have been dogged by controversy. The phasing out of single-hulled tankers in the late 2000s after a series of devastating spills led to dozens being converted into ore carriers.

The sinking of the 266,000-dwt VLOC Stellar Daisy (built 1993) in 2017, with the loss of 22 seafarers, was blamed on a catastrophic structural failure.

The Stellar Daisy had been converted 15 years later in a yard in China and approved by the Korean Register of Shipping, according to the official report on the disaster.

Three ineffective assessments while the ship was in dry dock failed to identify any potential defects with the conversion design.

But subsequent examinations of other converted ships identified structural problems that “brought the safety aspect of VLOCs into question”, according to shipowner group Bimco.