Vessels used to store oil off the West African coast are facing heightened security risks as they may need to stay in a piracy-prone area for long periods, according to a maritime risk consultant.

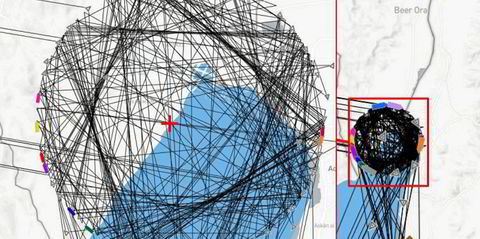

The number of product tankers used as floating storage in the Gulf of Guinea has been at a high level since April, mainly due to logistics constraints and contango play as Nigeria — Africa’s top fuel importer — faces a coronavirus-prompted demand collapse.

“Long-term floating storage certainly carries with it considerable risks. These risks are only able to be managed through a serious investment in vessel hardening and mitigation,” Dryad Global partner Munro Anderson told TradeWinds.

Vessels used for floating storage tend to stay 463 km (250 nautical miles) offshore or more to avoid pirates. Anderson said naval support would be limited at this distance.

“One of the best mitigations is to ensure that vessels are not stationary within the risk area,” he said.

On 14 June, Hafnia’s 69,999-dwt BW Tagus (built 2017) was approached by a fishing boat 250 nautical miles off the Nigerian coast.

The product tanker increased its speed to from nine to 14 knots and the fishing vessel eventually moved away.

While not formally on a storage contract, the BW Tagus was awaiting discharge orders in the Gulf of Guinea for nearly two months before the incident.

Ship protection

Many shipowners have opted to install barbed wire on board for perimeter defence while adopting measures to restrict boarding access and enhance monitoring.

But Anderson warned that barbed wire is “cumbersome to put up and store, easily corroding over long-term deployment and hazardous to crew safety”.

Shipowners should consider using specially designed anti-piracy barriers, which can be bought for about $60,000 for a 300-metre perimeter, according to Anderson.

“[These] are far more beneficial and are far more conducive to the protection of a vessel over the longer time frame,” he said.

If vessels are staying closer to the shore, shipowners can hire security escorts for about $10,000 per day.

But this would not be a commercially viable solution for tankers used for long-term storage, Anderson said.

Instead, he advised that shipowners with vessels within 100 nautical miles should consider a “community engagement plan” to foster goodwill with local leaders — which can drastically decrease the likelihood of being attacked.

“This is common practice for larger projects and can often involve the payment for services such as the supply of certain items of food, etc,” Anderson said.

“By investing in community relations, companies are able to drastically reduce the risk exposure of a long-term deployment.”

But he said locally-negotiated agreements can have problems and complexities of their own, and they should be handled with the help of established security experts.

Large floating storage

Kpler data showed that 9.42m barrels of clean petroleum products were stored on tankers off West Africa as of 29 June, including 4.71m barrels on LR2s.

This was much lower than the peak of 23.5m barrels recorded on 12 May but still more than doubled from the end-2019 level of 4.6m barrels.

“Oil majors and traders bought the products at cheap rates, and keep them in storage to sell them for later consumption at higher prices,” an African charterer said.

“Oil demand is recovering slowly, so it’s taking time for the cargoes to be discharged.”