Beyond the outskirts of Turku, the Finnish countryside blurs into an autumnal tableau as TW+ heads for the rural district of Piikkio.

It is an unlikely setting for a busy maritime enterprise involving multipurpose ships and the green technology for them, but this is where it all began for agribusiness/technical entrepreneur and shipowner Hans Langh.

Now 68, Hans took over the running of the family’s Alaskartano farm at 15, a year before the death of his ailing maternal grandfather, Carl Mattsson. The wooden mansion house dating from around 1850 now serves as headquarters of a €22m ($26m) turnover group.

Hans presides as group chairman, with a string of patents under his belt.

Elder daughter Laura Langh-Lagerlof, 36, took over as managing director of the shipowning and cargo solutions arms in 2015. Educated in maritime economics, she is also commercial director of its burgeoning scrubbers division.

Younger sister Linda Langh, 34, is a lawyer and since 2011 has been chief of the group’s industrial and ship-cleaning services.

Laura says they only recently moved back into the mansion following an extensive renovation. The project was meant to take three months but after wet rot was discovered, it ended up lasting almost three years. Their father has restored the building using the best local materials, including 1.5-inch (3.8cm) floorboards.

Linda carries Hans’ youngest grandchild, nine-month-old Edith, on her arm. “She’s the office mascot and senior advisor,” she jokes. Her other half is military officer Christian, and the couple have another daughter, Ingrid, who is two.

Laura’s husband, Sebastian, is sales director at cruiseship interiors specialist NIT. They have four boys: 10-year-old Victor, who was followed at two-year intervals by Arthur, Edvard and Conrad.

Both families live nearby. Their mother, Aila, is by turns interior consultant, entertainer of visitors and in charge of grandchildren, not least for the school run. The family have farming roots in southwest Finland’s Turku archipelago and Aland Islands. Mattsson bought the present farm in the 1920s.

Hans bought his first vessel in 1983 but says Mattsson and his great-grandfather were also shipowners in their time. From the 1920s to 1940s, Mattson, who studied to become a sea captain in Kristiania (now Oslo), owned small cargoships and passenger vessels sailing in the archipelago. His father was a captain-owner of even smaller sailing boats.

Mattsson went bankrupt but continued to farm at Alaskartano. Hans’ father died when he was only two, so he grew up under his grandfather’s wing. “He was really a father to me,” Hans recalls.

Before Mattsson’s death in 1965, he and Hans had been working together on a commercial version of a grain-drying machine. Hans took on the task of designing and finishing the project on his own. That spirit has defined his career ever since.

That first business was built on drying grain for local farmers. By the late 1960s he was offering a complete package, including harvesting and transport. He soon recognised the market potential in shipping for drying wet grains left over in the holds of vessels discharging in Turku. Low-grade dried grain could then be used as animal feed.

Shipping sustained the business during winter, but its days were numbered.

“In those days hatch covers tended to leak a lot,” Hans says. “MacGregor-Navire then developed new hatch covers that were very good, but it was a catastrophe for [my] business.”

Forced to think anew, alongside selling gravel he invested in high-pressure cleaning equipment to shine up heavy construction and earthmoving machinery on site prior to servicing. That soon extended to agricultural kit and livestock pens in the 1970s.

“Trucks and tractors would get a better resale price if they were clean and looking good,” Linda explains.

But then local farmers started to buy their own equipment — a second blow to the business.

In the 1980s, Hans’ next bright idea was to devise a new suction-based method for cleaning ship tanks and bilges.

Up to that point the practice had been to drill holes in the underside of tanks while a ship was in drydock, inject steam to heat up the oily residue and let the slops drain into barrels below the hull.

“It was a very slow process,” Hans recalls. “Ours was a completely new method that was much quicker and cheaper. Plus we could clean the tanks while the ship was in port.”

Today, tank, pipe and bilge cleaning can be performed while ships are underway, with wash water removed in port and treated. Key customers include Finnlines and Viking Line. The company also works with local shipyard Meyer Turku on cruise newbuildings.

“There’s still a lot to clean before painting work can begin. For example, we also ensure engine rooms are clean throughout the building process,” Linda says.

Her portfolio now covers many other sectors. The company is also involved as the cleaning supplier in a project supported by state funding agency Tekes that aims to start commercial shiprecycling at Turku Repair Yard. A pilot vessel, the 60-metre passengership BlueWhite Eagle, was cut up in October using giant steel clippers.

On the shipowning side, after the purchase of the 3,100-dwt cargoship MS Laura in 1983, Hans adapted the cleaning technology to four German-built multipurpose newbuildings that enabled holds to be rapidly cleaned and dried after the discharge of dirty bulk cargoes.

Those ships were delivered in 1989 and 1991 from JJ Sietas in Hamburg, where all the company’s nine newbuildings to date were built. “It’s a very good yard,” Hans says. “All the ships are a container design with the tank top strengthened for bulk cargoes.”

Today the fleet comprises five ships — the 6,527-dwt/466-teu sisters MS Marjatta, MS Hjordis and MS Laura (all built 1996) and 11,497-dwt/907-teu duo MS Aila and MS Linda (both built 2007). All are ice-class with big engines.

Four of the original nine newbuildings were sold before the newest pair arrived.

The 1996-built trio were tailor-made for Finnish steel producer Rautaruukki in a relationship that started in 1989. Today they are employed long-term by Finnish steel coil producer Outokumpu.

Laura says that before being merged into Swedish-Finnish steel group SSAB in 2014, Rautaruuki had already been combining cargoes from its stainless-steel factory in Raahe with black steel from Outokumpu’s plant in Tornio, both in the Gulf of Bothnia.

“The Outokumpu trade is kind of A to B because we’re like an internal factory link,” she says. “They manufacture steel coils in Finland and do steel cutting at their factory at Terneuzen in the Netherlands.”

Langh has long experience in the icy north, with its former 4,454-dwt Christina (built 1991) the first ship that traded year-round from Tornio in the 1990s, Hans says.

There is no spot business. “Sometimes we’ve had trials to fill space on ships but luckily Outokumpu fills everything,” Laura adds.

The entire Langh fleet is managed in-house, including crewing and technical management. All the ships are Finnish-flag and under the country’s tonnage tax. “We have considered flagging elsewhere but we always reach some kind of compromise with the unions,” says Laura Langh-Lagerlof.

The company employs around 100 seafarers. One-third are allowed to be non-EU nationals under the company’s latest union agreement. That will probably happen naturally, Laura says.

All chartering is done in-house, so the business is direct. “There are no brokers involved,” she says.

The vessels are mainly transport containers developed by the group’s cargo solutions arm, specially designed to carry steel plate and coils.

“There is always competition but customers appreciate our patented equipment onboard,” Laura adds.

Other innovations include a cradle system in the hold that ensures vessel stability while protecting easily damaged cargo.

“The steel has to be evenly loaded, also on the tween deck. Having two tiers completely changes the GM [metacentric height] of the vessel. The load on the tank top is spread higher up, possibly also with containers, so the ship moves much smoother in heavy seas,” Hans explains.

Previously, in bad weather, a vessel might have to steam for up to two days in the wrong direction to maintain stability.

Meanwhile, Langh’s 2007-built vessels are on long-term charter to Helsinki's Containerships, which provides door-to-door logistics using a fleet of feeder-size vessels. “They don’t do normal feedering. It’s mostly 45ft containers just within Europe, not continuing overseas,” Laura says.

Assessing the shipping market, she adds: “It’s been tough years since 2008. Just look at the situation for German owners, who have similar types of multipurpose vessels. But we’ve managed quite well, and our long-term customer relationships have of course helped.”

The company is not actively searching for new trades. “We do our best for our present customers,” Laura says. “But we always keep an eye on the market. If we saw a ship and the opportunity to do standard feedering, why not.”

They were looking at a secondhand opportunity this autumn and are “absolutely not against newbuildings” if the business case is there.

But speculative deals are out of the question.

“We need to have the employment,” Laura stresses. “We trade in such niche markets. We watch what’s going on in the Baltic and Northern Europe but our business is kind of separated from the global shipping markets.

“Of course we read TradeWinds to follow what’s happening!”

Ship financing was formerly with Germany’s HSH Nordbank. “For the newbuildings it was quite logical,” Laura says. Her father adds: “We were customers of the bank for 25-30 years.”

But nowadays the company has Finnish financiers.

The family has never been tempted to go public. “We’ve never even discussed it, seriously at least,” says Linda.

Laura adds: “It’s quite easy and simple as it is now. The three of us can decide to do whatever we want. Just do it!”

Work is a hobby for hands-on Hans

Hans Langh is a practical man who clearly enjoys getting his hands dirty.

“That’s still the case,” elder daughter Laura Langh-Lagerlof says. “Whenever a vessel goes into dry dock, he likes being there on site.”

Last year Hans was at Nauta Shipyard in Gdynia, Poland, for three dockings. “I inspect the ships myself — tank cleaning, painting, welding, everything,” he says.

He also supervised the construction of the company’s new water treatment facility in Piikkio.

The secret of his success is, simply, to focus on customers’ needs. “I always tried to solve their problems and to think of something new.”

He also stresses the skill of putting together effective teams. “Always select the right people with the right competence,” he says, “and then give them as much authority as possible to make decisions.”

But the greatest lesson he has learnt is never to make hasty decisions: “Small steps over time. Big decisions have to be built on a solid foundation.”

And, he advises, “Be careful, because after a time when things are going well, there’ll always be a downturn. In roughly five-year cycles.”

The worst slump Hans experienced was the banking crisis and recession in Finland at the beginning of the 1990s. “I sat on the board of Abo Sparbank. It was really difficult,” he recalls.

A previous downturn in the early 1980s had an upside, when he bought his first vessel. “The 3.5-year-old MS Laura cost 20 million Finnish markka to build but I bought it for 10 million Finnish markka. And I sold it for the same price when it was 12 years old,” he says.

“It was lucky timing,” younger daughter Linda adds.

The market can be fickle. “Earlier this year vessel prices reached the bottom. Prices can go up for small ships [like ours] but they can also fall 50% in a year,” Hans admits.

The family has gradually been buying more land in the surrounding area. The farm now extends to 330 hectares (815 acres) with an equivalent amount of forest. He cultivates mainly wheat, barley and some rapeseed that is sold locally. Besides the farm and his grandchildren, “work is my hobby. But farming is so different to shipping, maybe it’s that.”

Linda quips: “In Finland it’s hard to make any money from farming. That’s why you can think of it as a hobby.”

From classroom to boardroom

Laura and Linda Langh always knew they wanted to follow in their father’s footsteps. “We never once ever thought of not doing so. Hans played his cards right,” Laura says. “It’s been so interesting all the time.”

“Even when we were at school we’d come into the office and work on small tasks,” her sister adds. “Then slowly we got more and more responsibility.”

Even in the early stages of managing their respective companies, Laura says they were given a free hand. “Of course we always ask Hans if something has been done previously. He’s the founder and is still very much into the details. We work really well together.”

The pair complement each other. Laura gesticulates: “I’d be signing contracts all the time — snap, snap, snap. But I always go to Linda and ask her: read this. As a lawyer, she thinks and considers.”

There are six horses on the farm and both sisters are keen riders, but work dominates conversation when the families gather for Sunday lunch.

“We always talk business. Mum sometimes gets frustrated. ‘Please can we talk about something else!’ she says,” Linda laughs.

Working in such a male-dominated industry doesn’t faze them. “I’ve never paid any attention to it. Many times in meetings I’m the only woman,” Laura says.

Nor do they consider themselves role models. “There are plenty of women in the business, and more and more are coming,” Laura says. And not only in Scandinavia. “In China, for example, there are many women in the technical departments of companies.”

In the loop

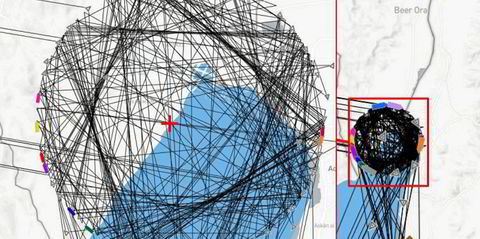

The Langh group’s five owned ships have been fitted with scrubbers developed in-house, and Laura Langh-Lagerlof is busy taking this big new business field global.

“We’ve been selling to other owners for two years, and now have over 20 vessels equipped with our scrubbers,” she says — primarily cruiseships.

Its systems are designed for both retrofit and newbuildings.

The move happened by coincidence. “Our customers brought up the subject when it was known there would be the 0.1% SECA [sulphur emission control area] limits, and we are 100% trading within the SECA area.”

Helsinki-based Containerships, which has two Langh vessels on long-term charter, was the first to install a scrubber on its one owned ship.

“We checked out LNG conversion but we knew right away it would be too expensive,” Laura says.

When they started, she admits they “hardly had a clue” about exhaust gas cleaning but the group set about engineering a lightweight system with low operational costs.

“We needed closed-loop scrubbers, as we trade to the northernmost part of the Baltic where the seawater is not sufficiently alkaline to use as process water,” she explains. Using open loop would require switching to marine gas oil.

The company installed the first scrubber in 2013 on its MS Laura. “We did a lot of product development simultaneously, testing different solutions. First we checked offers from existing suppliers but we decided the technology was not yet that advanced.”

The closed-loop system uses fresh water and sodium hydroxide to neutralise sulphur.

Laura says no existing supplier had cracked the key water treatment issue in 2011-12, so they opted to use the same membrane-filtration technology developed by Langh’s industrial cleaning operation.

“That turned out to be very valuable knowledge, as we are now selling the water treatment component to other scrubber manufacturers,” she says. It is also being applied to process water used in exhaust gas recirculation systems.

Having scrubbers on its own ships is a big benefit for the company.

“We can take potential customers onboard and even sail a short leg so they can see how everything works,” Laura says. A mini-scrubber installed in its new cleaning plant in Piikkio is used for demonstration and training.

A hybrid system that can be operated in open-loop mode has also been developed.

Laura sounds a note of caution on what she perceives as a movement among owning companies trying to influence the International Maritime Organization’s 2020 global sulphur cap decision by suggesting scrubbers are not reliable.

“It’s been in the press that scrubbers are expensive and owners have been considering LNG conversions as an alternative. But if they don’t get the figures to match with scrubbers, they’ll never get them to match with LNG conversion! It’s several times more expensive.”

The payback period for the scrubbers has been around 3½ years. The cost of all components, installation and commissioning was in the region of €1m-€2m ($1.16m-$2.32m).

The company is also working on a new related project that will come to market around the second quarter of next year involving a “technical improvement in emission reductions”.