Billionaire shipowner John Fredriksen’s key companies roll off the tongue like a who’s who of the maritime world, but one of them has been less visible than the others.

Tanker giant Frontline is arguably the best known of all his firms. Bulker owner Golden Ocean is synonymous with one of his flagship deals, in which he took the company over from Fred Cheng as a tanker play and transformed it into one of the largest dry cargo fleets on Wall Street. Now Flex LNG has joined its siblings in New York, sailing around the five-year US shipping IPO dam and dancing into the world’s largest capital market in the same style as Spotify.

Ship Finance International Ltd, which has just been renamed SFL Corp, has been a different animal. Seldom grabbing the same splashy headlines as its stablemates, it has operated a little below the radar despite a market capitalisation in excess of $1.54bn and a record of continued profitability stretching back 15 years.

Perhaps it is not surprising that SFL has a lower profile than its sisters. Fredriksen himself does not list the company in his shipping portfolio. Instead it can be found on the more stable side of his ledger, alongside Norwegian property ventures and salmon-farming titan Mowi, formerly Marine Harvest.

It is not only the profit that has been steady. SFL has paid a continuous dividend for well over 60 quarters, returning in excess of $800m to Fredriksen alone. At the same time, it is, along with Mowi, the only company in the Fredriksen system that has not called on the tycoon for financial support in the past five years.

“We know it’s phenomenal to have a big investor who has shown so much commitment and support,” SFL Management chief executive Ole Hjertaker says. “We think of this as our last line of defence, but build our risk-management philosophy around multiple defence lines. Then, even if something does happen in our portfolio, we hopefully have the flexibility and resilience to manage it. And if you should break through our other defence lines, we can only hope that John would step up and help us as well.”

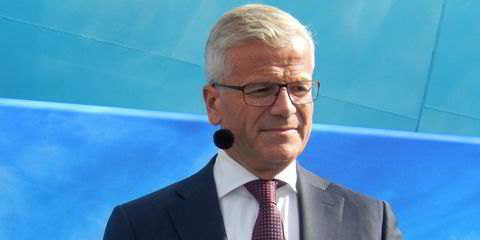

Hjertaker, a tall, flamboyant figure, has been with SFL for 13 of its 15 years. The period has seen some traumatic market movements, in shipping and the wider economy.

“In shipping, if you look in the rear-view mirror, it’s a market where companies seem to go from ditch to ditch. Very few manage to stay up on the road and be self-propelled,” he tells TW+ during an interview on the top floor of Fredriksen’s main shipping office in the Oslo waterfront district of Aker Brygge.

Having ridden out the global trade collapse after the fall of Lehman Brothers and sailed through the tanker crash of 2011 — despite a restructuring of Frontline — SFL faced a severe slump in the offshore market in 2016.

“Working in the maritime space, severe cycles are what you should expect,” Hjertaker says. “It’s a combination of deal structuring, risk management and how you deal with issues when they arise that hopefully distinguishes us a little.”

John Fredriksen aims to open his shipping empire to new management and ownership. The 75-year-old hopes to hand more responsibility for and ownership in his network of companies to a new generation of executives who have sufficient resources to run them. “I am looking for people who can take over,” he said, adding that the moves would allow his twin daughters to follow a different path.

Fredriksen still wants to do some private shipping business, to “own and operate some ships besides all the stock-listed companies. This would be sort of going back to my roots. I enjoy this, and it fits me well as I am getting older.”

During the major restructuring of Seadrill — which Fredriksen has called the most difficult task of his long career — SFL tightened its purse strings. “Instead of putting money to work, we kept it on our balance sheet,” its chief executive says.

However, after Seadrill struck a deal with its banks and bond holders, SFL was quick to dust off its chequebook. Last year it executed a $1.2bn growth drive with four major transactions, making it the most active company in the Fredriksen group.

“We were a bit underinvested during the Seadrill restructuring and we felt it was better use of money to have the visible strength instead of investing and potentially being perceived as vulnerable in that situation. So, of the $1.2bn last year, some of that you could argue was a catch-up from the prior year,” Hjertaker points out.

Also deviating from the typical Fredriksen script was SFL’s focus on containerships in 2018. All four deals, including one with Lemos that saw the conservative Greek family become a major SFL shareholder, involved boxships. SFL now has 50 containerships in its fleet of 92 marine and offshore assets.

“We are the only company where Mr Fredriksen is directly exposed to containerships,” Hjertaker notes. “For SFL, it’s natural as we look for opportunities to charter vessels long-term to end users and the liner companies who are an important piece of the logistics puzzle.”

Aksel Olesen, who joined SFL as chief financial officer in January, says being part of the Fredriksen system offers many advantages, including “better access to shipyards than most other people out there”.

As a repeat customer, better delivery slots, more competitive pricing and higher specifications are often possible, while finance is also more readily available, because SFL is “a bigger fish in a relatively small pond”.

“We can structure as effective financing as anyone else in the market [so] you can possibly make a combination that is creating value for customers and where we can hopefully get a better return on capital,” Olesen reasons.

Despite its focus on boxship deals last year, the liner space is not the only target on the radar.

“It has been our strategy to build a diversified portfolio in terms of asset segments and counterparts, and we’re constantly working on our product offering as the maritime financing landscape is shifting. Not only are we looking to be diversified on the asset and counterpart side, we’re also looking at expanding our toolbox for more bank-like structures,” Hjertaker says.

He is referring to SFL’s most recent deal, the acquisition of three VLCC newbuildings announced in early September in a sale-and-leaseback arrangement with the Oslo-listed Hunter Group.

“In this transaction, we were able to offer a more flexible solution than the banks, and it is a great example of how SFL can create value in an environment where banks are pulling back. With our balance sheet and track record, we have superior access to financing compared to a shipowner with a limited number of vessels,” Hjertaker says.

“The fact is, we’re more a specialty-finance company than a shipowner. In the Hunter transaction we’re using our strong balance sheet to extract value through capital cost arbitrage.

“We have $4.5bn in enterprise value. The world fleet shipping and offshore is more than $750bn. Financing of that is around $400bn. There should be room for growth without being in a situation where you become too big for the market.”

However, the company and its major shareholder are not setting firm targets. “We would never tell investors how much we will invest,” Hjertaker says. “We will never tell investors which segment we will invest in. We think that is the way we may end up in trouble. If we say we have to invest $500m per year, then you could feel compelled to do investments when you really shouldn’t make them.”

Hjertaker also offers a rare glimpse into Fredriksen’s approach to shipping investment: “Mr Fredriksen has been in the business so many years. He has seen so many cycles. Having him there as a large investor is a strength.

“When we discuss new business with him, it’s all about timing and doing the right things. Don’t rush anything. Hold back if you need to, but then when the right opportunity is there, you can move quickly and do size if everything else is right around it.

“If you look at the financial markets, it’s tempting shipowners to invest at the wrong time of the cycle. The equity markets are open at the peak of the cycles and when the banks will give you more leverage. If you are focused on one single segment, that’s when the money is there.

“Would you not be tempted to invest when money is thrown at you? Being diversified as we are, with four main shipping segments, we can benchmark deals between them. We try and observe what’s going on in the different segments and if things are going too fast, we focus elsewhere.”

SFL has a time horizon of 10 or more years when evaluating new transactions and understands there will be volatility and unexpected events during that time frame.

“It’s all about trying to invest in the right type of technology and the right type of assets and not ending up buying the wrong asset or old technology,” Hjertaker says.

“That is why we have been careful on the LNG side, where there has been a technology shift in the last 10 years and the economic life cycle for some vessels may be much shorter than the investors hoped. When a new vessel saves 100 tons of fuel per day compared to older vessels, you don’t have to be a rocket scientist to understand that it has an impact on residual value. There have been a lot of deal opportunities for steam turbine vessels with high charter rates for a couple of years, but we have been very careful.”

Despite a celebrated 2018, which saw SFL in the limelight more often than it is accustomed to, its executives are not ready to crack open the champagne.

“It’s a long way before we can say, ‘Yes, those investments are really great’,” Hjertaker says. “You only know that afterwards. So far we have not regretted any investments we did in 2018.

“An observation on the market in general is you get a lot of attention when you do a transaction. In shipping and maritime, you should really focus on when you get your money back with the return.

“That is where so many get it wrong. They make the investment. It looks good in the near term, but what if the vessel does not last the 25-30 years? Maybe it only lasts 15-20 years due to a technology shift and you have to take a loss in the end.

“So one of the issues we have as an industry at large is to demonstrate consistency in returns over time for investors. That is why so many investors are careful touching shipping, as many have burnt their fingers.”