If you’re going to dream, dream big, the saying goes. It is precisely what Roger Gooch, a marketing visionary, and a few other like-minded dreamers are doing in a small office in Altamonte Springs, Florida.

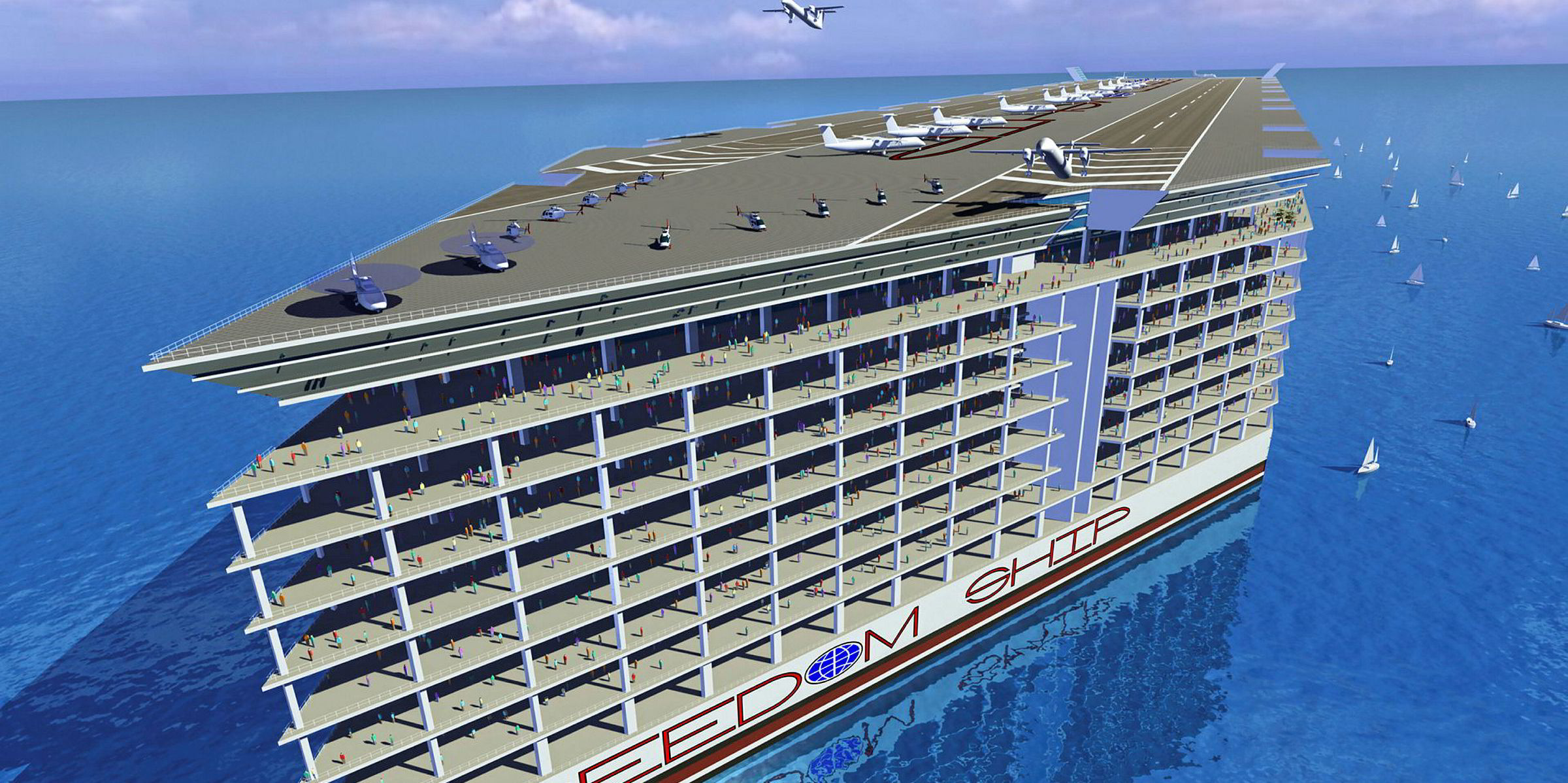

They are working on the Freedom Ship-City at Sea project, a plan for a larger-than-life cruise vessel that, if ever built, would carry 50,000 residents and circle the globe every 2½ years, making weekly stops 25km (about 15 miles) off major ports.

The gargantuan ship, 1,500 metres long and 100 metres high, would have room for up to 15,000 visitors and 12,000 employees.

“No port can accommodate a vessel of this size,” Freedom Cruise Line International chief executive Gooch admits, but adds: “The size was required to avail the inhabitants the services and amenities of city living at a cost-effective basis.

“It would be the only venue that would enable the continuous worldwide showcasing of eco/green technology and enhance global environmental awareness and potentially directly aid in oceans clean-up processes.”

The ship would be propelled by an azipod system and kept afloat in bad weather through “advanced weather instrumentation”. But for now, the project exists only as computerised renderings that began appearing many years ago. “Detailed base platform design will commence shortly, pending capitalisation,” Gooch assures TW+.

Such an enormous ship might be built in the distant future — but not with today’s technology and materials, counters Rick Ashcroft, a naval architect with 45 years in ship design and construction.

“There are always people out there with a pipe dream that looks good on paper but they don’t think through the engineering or the maintenance,” he tells TW+. “The practicality of this vessel just escapes me.”

Even if it is built, most countries probably would not allow such a behemoth to anchor outside their ports, which need to be kept clear for other traffic. “You can’t just hang out with something of this size,” Ashcroft adds.

Despite such scepticism, Gooch is flanked by directors who take this vision as seriously as he does.

They include executive vice president Peter Banas, a retired FBI special agent; president Robert Pflueger, a Florida bankruptcy lawyer; logistics vice president Wesley Green, a former US Army special operations officer and combat veteran; and information technology vice president Eric Chia, a product engineer.

While the design phase is well underway, these visionaries still need to come up with $10bn to turn the City at Sea venture into an actual ship.

That’s where the Global Development Incorporated Group, based in Hong Kong, comes in as the project’s main backer.

“They have committed to raising the necessary capitalisation to bring this project to fruition,” Gooch says.

He does not disclose how much money has been raised so far, although it’s “not enough” to begin building the vessel. But he adds: “We are confident that Global Development will avail the project to the necessary capitalisation to begin primary construction operations this year.”

Global Development supports several industries, from housing to education to agriculture, according to its website. It lists no current projects.

Freedom Cruise plans to begin building the ship with “a number of construction entities” over three years. Gooch estimates that 5,000 to 10,000 workers will be involved once primary construction operations begin.

When that will happen is anyone’s guess but he remains determined that Freedom Ship will roam the high seas one day.

“The global interest and demand for this ship and its unique amenities is most evident,” he claims. “It will assuredly come to fruition if the necessary capitalisation is obtained to commence construction processes.”

A ship this size presents an endless list of other challenges, such as dry-docking for regulatory hull inspections and repair, Ashcroft points out. “Where would you do this?”

Classification societies suggest hull inspections be done underwater in “very clear waters”, since no dry dock in the world can take such a large ship, Gooch responds.

Large offshore rigs are inspected “in water” because they cannot be dry-docked, but seagoing vessels are taken off the water every five years for inspection.

However, some ships have agreements for dry-dockings every 7½ years, when two consecutive examinations of the hull are carried out by divers or remotely operated vehicles, Lloyd’s Register says.

“With the proper design and construction, and with the agreement of flag, it may be possible to extend this further but there may be technical challenges to overcome with respect to the coatings and maintenance,” the class society adds.

Ashcroft pinpoints another problem: the Freedom Ship would have to withstand the worst ocean storms without any real ability to get out of the way.

Gooch responds that it would easily sustain violent weather because it would displace 2.8 million tonnes of water. “It has been affirmed from our engineers that a 100ft [30-metre] wave hitting the ship laterally could potentially move it just a little over one inch,” he claims. State-of-the-art meteorological and navigation aids will allow the ship to adjust its itinerary to avoid bad weather, he adds.

The vision for the 250-metre-wide Freedom Ship emerged in the early 1990s from the late Norm Nixon, a Florida engineer.

When Nixon died in 2013, it appeared the project was “all but dead”, Gooch says. However, he insists, the vision remains. Although a ship of this size and nature has never been built, “We foresee floating cities in the near future to be potentially commonplace.”