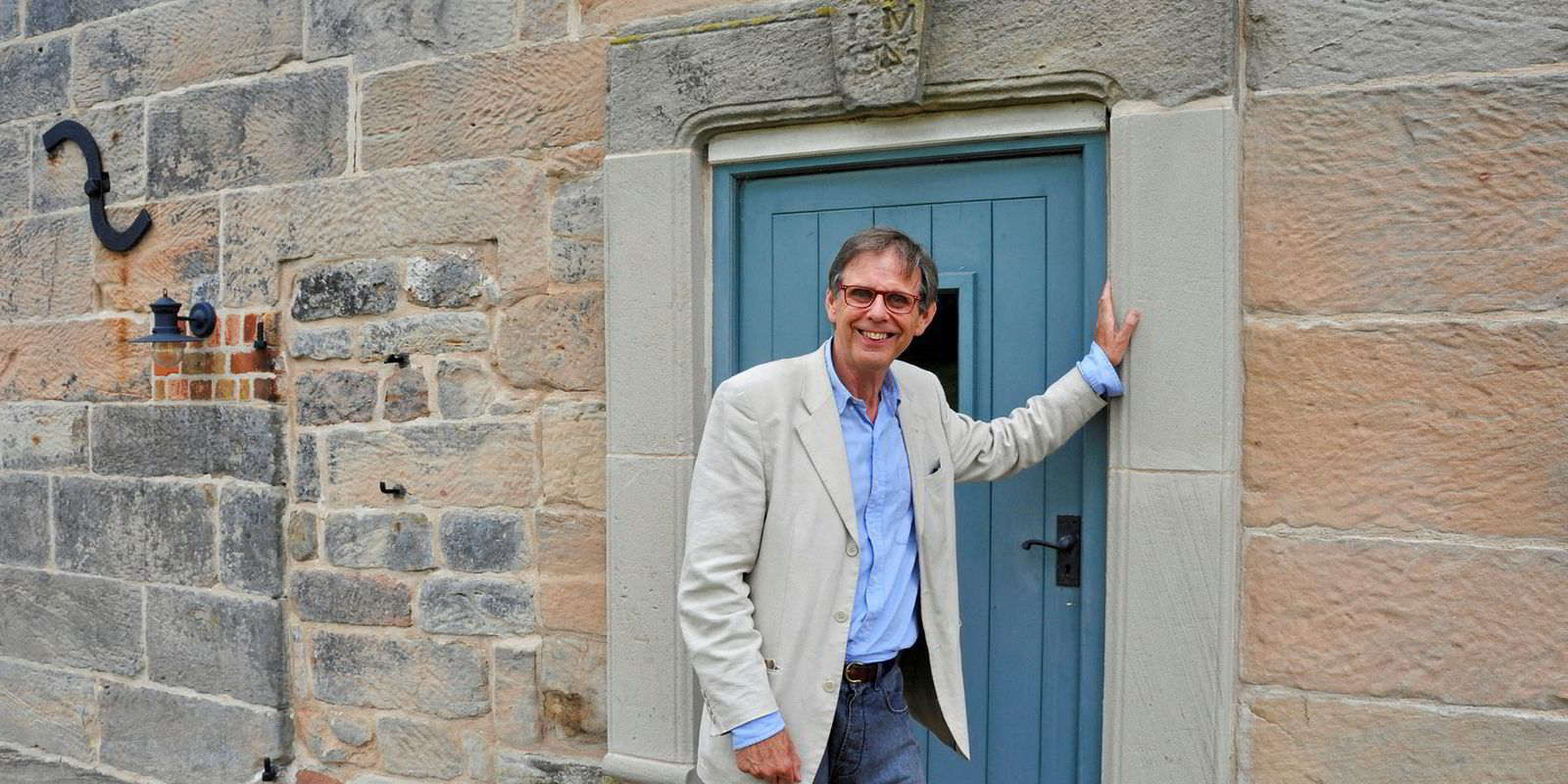

Shipping’s favourite forecaster, Martin Stopford, says his 109-acre Crumpwood Farm in the heart of rural England was an impulse buy.

After finishing the third edition of his book Maritime Economics in May 2009 at the age of 62, the research guru found himself with time on his hands.

He had got into the habit of browsing details of farms for sale and spied the property in Staffordshire, central England, drove the 150 miles (240km) from London to view it and three months later found himself the proud owner.

Farmland was doing well, Crumpwood was not expensive, he says, and with its six-bedroom farmhouse, original farmyard, derelict stables and cart shed, plus a historic Shrewsbury barn, it had potential, because unlike many similar properties in the south of the country, it was almost untouched.

“Your imagination sees things as they might be,” he says. “It doesn’t see the blood, sweat and tears along the road.”

The organic farm is in a beautiful spot, a short walk from the village of Alton — home to the Alton Towers theme park — and there is no other habitation in sight from the farmhouse, giving it a tranquil, isolated feel. The property includes a small river valley, water meadows, beech woods and a spectacular cliff.

A former colleague at shipbroker Clarksons, where Stopford remains non-executive president of Clarkson Research Services, had connections in the area and put him in touch with the local postman, Barry, for the low-down on the place. Barry’s verdict on Crumpwood: “A rock star’s retreat.”

Stopford arrived on the farm at night in a white van with a bed in the back. He knew nobody, had only a sketchy knowledge of the rudiments of farming and was not entirely sure what he was going to do. The barns were all empty and he could not even find any wood to light the ancient Rayburn stove.

His son Ben says the Crumpwood purchase was “heart over mind”.

“I’d say it was an adventure,” is how Stopford puts it. “It was something completely different.”

He started out spending every weekend at the farm, driving up from his day job at Clarksons in London on Friday nights.

On Saturday he would get up at 5am to do his own work and at 8am would meet the men who had been working on the property during the week to catch up on what had been done. He then cracked on with farm work before setting off back to the capital late on Sunday.

As a teenager, Stopford enjoyed repairing old motorcycles, progressing to renovating houses as he got older.

“I think my skill is solving problems,” he tells TW+, explaining how he eradicated the persistent damp in the farmhouse by building a French drain with a camber around the property and diverting the spring that ran under the house. He expresses admiration for the array of local craftsmen and workers who have helped him transform the place. It has not always been harmonious: “What irritates the people I work with is that I keep changing my mind. But you keep thinking about a problem and find the better way to do it.”

Phase I was work on the farmhouse, which is Grade II- listed (a conservation status for historic or special-interest buildings). Stopford uncovered what are thought to be original ships’ timbers in the attic bedroom floors and replastered the walls in the traditional way in which they would have been built.

Phase II was to rebuild and renovate the former stables and cart shed as holiday cottages. Stopford describes this as a “planning nightmare”. He recalls sitting on a plane in Hong Kong waiting to take off when he received a call saying his planning application on the properties had been turned down due to insufficient information about bats, which are protected species.

Under his original planning permission for Crumpwood, the plan was to pull down the farmyard and relandscape it. But he felt the farm not only needed a farmyard for the animals, when they arrived, it also gave the place “a bit of heart”.

“To me Crumpwood Farm as a farm is worth a lot more than Crumpwood Farm a rambling farmhouse with two cottages.”

Stopford is upfront that the farm purchase is not a tax break. “I’ve never taken a penny out of the farm. I’ve always treated it as my own budget, not as a tax thing.” He is the registered farmer who, in his words, “makes the grass grow and mends the fences”.

But when he is on the farm he is still thinking about shipping.

“Farming is very like shipowning,” he says. “I don’t think you really do it for the money, although you might get lucky and make some. But I think people do it because it is something they want to do.

“There are not many businesses on the scale of shipowning that you can do as an individual and really look at that and say, ‘I built that business’,” he adds, citing legends such as Captain Panagiotis Tsakos, John Fredriksen and Sammy Ofer.

Having spent my life behind a desk, I felt it was time I reminded myself that I could do an honest day’s work

“Shipping is uniquely a business where you can build up billions of dollars of assets with a principal and one or two trusted henchmen.

“This is something that comes from great depth of judgment, personality, sustainability and the ability to work with other people. In a sense you build the company, but you still have to manage all the problems that come up along the way, and often that is about getting the right people to help you. I think farming, in a smaller way, is very similar.

“The other thing about farming is half the time you are losing money, so it is very like shipping in that you are struggling to pay your operating expenses and keep the bank happy.

“One of the reasons I was keen to do it is that having spent my life behind a desk, I felt it was time I reminded myself that I could do an honest day’s work.”

In his office job he never really felt at the sharp end of things. “I like doing things. So I guess if you can’t afford a fleet of 50 tankers, then maybe buying a tiny rundown farm is the sharp end of real life and not a bad alternative...

“You’d be surprised how many people in and around shipping do have a small farm tucked away somewhere.”

Today he thinks Crumpwood Farm would be a great place for a couple in their 30s with kids who are trying to make a go of it, and in one sense he wishes he was 35 years old again.

But now a grandfather to three, he sees a parallel with his one-time dreams of big motorbikes. “At 20 I lusted after big Triumphs, but when you can afford it, you don’t really want it.”

Stopford, who ditched his TV a few weeks before TW+ visited, now spends two to three days a week on the farm.

He is thinking of selling up but is also considering staying on to complete Phase III of his “adventure”. This includes reroofing the barn, refurbishing the farmyard to make it better for overwintering and getting the cottage rentals up and running.

In the longer term he would like to make better use of the water from the trout-filled River Churnet — where he found the remains of another shipping connection: an old dock called Cotton Quay, which provided a direct link via the regional canal system to Liverpool.

He would also like to develop niche farming ideas, planting orchards of traditional fruit, bringing the dilapidated chicken shed back to life and improving the green footprint of the cottages.

“I should end up with something that looks well-worn but works well,” he says. “Once you start, you’ve got to carry on. You put to sea in your ship, you can’t suddenly go home and go to a hotel for the night — you’re on your voyage, mate.”

He admits he could put in to a small Greek island, moor up and sit on the beach, but gives himself three days until boredom would set in.

Is he glad he embarked on his farming adventure? “I feel it is part of my life — an unfinished part,” he replies. “The voyage isn’t quite over yet.”