Florida and Miami — or at least shipbroking, former shipowning and prospective mega-cruise liner project executives based there — take a fair deal of the spotlight in this issue of TW+.

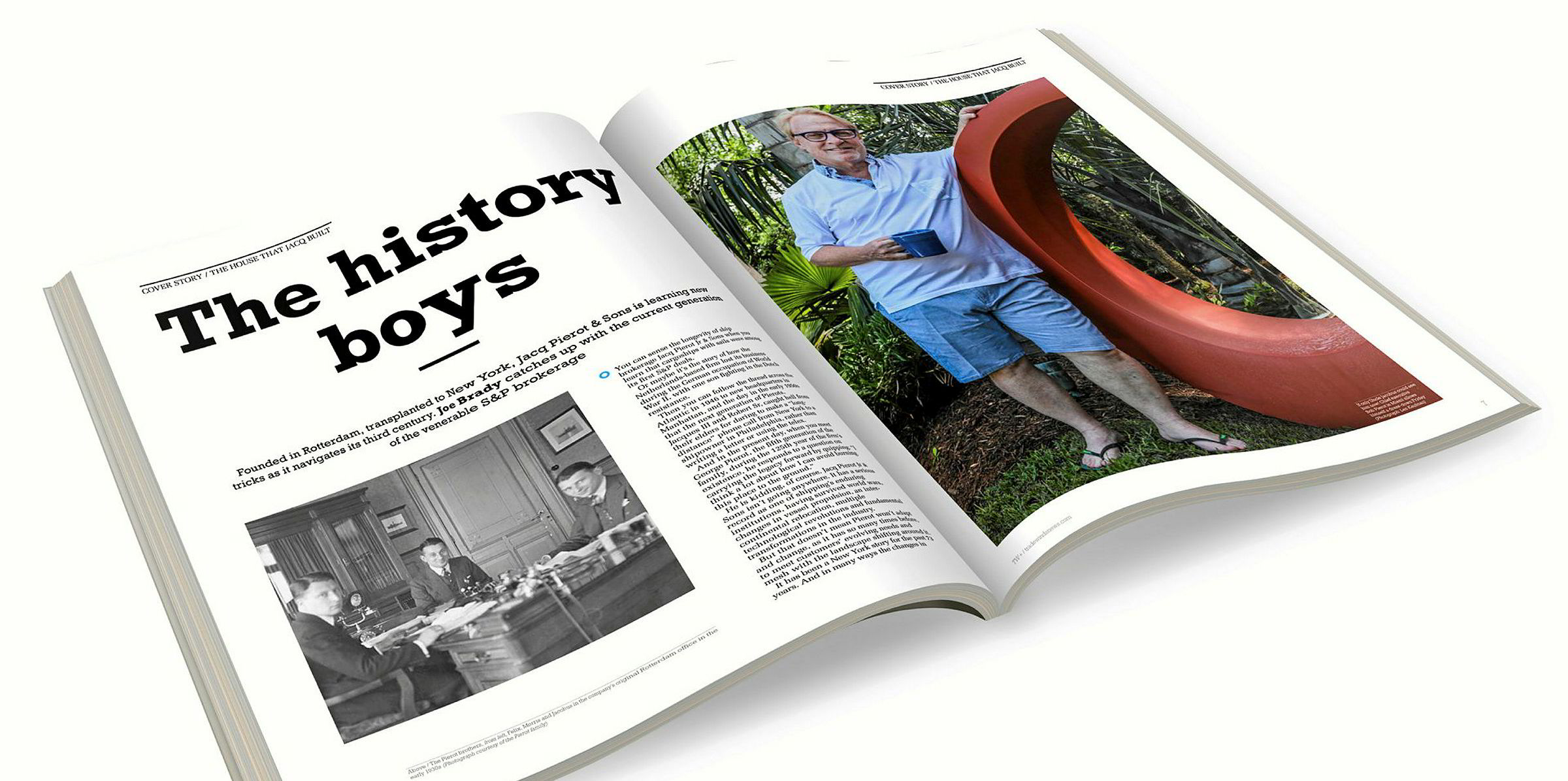

Robert “Bob” Pierot reveals why he moved to Miami last year to pursue ship finance structuring deals, with cargo-owning clients as well as owners, that are an increasingly necessary adjunct to the New York-based family firm’s traditional expertise in S&P shipbroking, where it has been a force for 125 years.

James Christodoulou, the shipowners’ “IPO king” who was Peter G’s right hand-man when Genmar went public in 2001 and arguably paved the way for the bull run of listings in 2005, waxes lyrical about his new life in the Florida city getting electric car charging company Blink off the ground — and assuring us he is not out of shipping, because once in, it is just not possible to leave.

Then there are the proponents of a vision to build a vessel four times longer than the world’s largest cruiseship based a bit further up state, near Orlando. They envisage it would carry 50,000 residents, circle the globe every 2½ years and make weekly stops, anchoring 25km off major ports.

So it is pertinent that this edition is going to the printers just days after Hurricane Dorian wreaked so much havoc off the coast of Florida when it ground to a halt and tore apart the Abaco Islands in the Bahamas. If the storm had moved inland more quickly, the devastation that left the islands looking as though a nuclear bomb had exploded could have been wreaked upon Miami.

And what has that to do with shipping?

Pressure is building for the industry to do more to cut carbon emissions that are widely accepted to be a factor in climate change, with hurricanes’ greater intensity and slower movement over sea believed to be caused partly by warmer oceans.

We also highlight the first attempt by a group of shipping banks to green up their ship lending policies and portfolios of loans with guidelines to oversee a reduction in marine carbon pollution.

The Poseidon Principles bring together 11 financial institutions that account for $100bn of the total $450bn of ship finance outstanding to the industry in making a commitment to cut carbon pollution from the fleets they finance.

Pierot says the off-balance sheet deals he is involved in focus on Tier 1 clients that banks want to lend to, often involving cargo interests that are stronger corporate entities than most shipowners. He describes his job as, in effect, seeking to create long-term structures for cargoes to move on ships.

These interests are most likely to be the very clients that the Poseidon banks will want to work with as they implement the finer details of their plans.

Although he does not claim to know what new technologies will come through, Christodoulou is convinced electric power will make its way into ships, and that electrification of societies will change trading patterns. And he accepts that the way capital markets want shipping companies to be run is ill suited to the best ways to run those companies, which need patient capital backers able to understand and accept market volatility.

Attempting to raise finances to build the gargantuan Freedom Ship, 1,500 metres long and 100 metres high, with room for up to 15,000 visitors, remains a long haul for the company behind it.

Despite claiming it would be a venue for showcasing ecological technologies, it is hard to see how a power-hungry and potentially polluting city on the sea would enhance global environmental awareness as Freedom Cruise Line International chief Roger Gooch says. And quite how much fun it would be on such a ship if it got anywhere near a Hurricane Dorian and was unable to outrun it is quite another issue.