Shipowners and operators wanted. It’s not quite a lonely hearts plea, but a commodities futures exchange with a strategy to expand globally in freight derivative trades would like more shipping companies to get involved.

Cleartrade Exchange, the Singapore-based futures platform fully acquired last year by Deutsche Borse’s EEX Group, is on a mission to link the companies’ strengths in power and energy with the movement of freight and fuels.

“It would be good if more shipowners trust and come into the market,” Cleartrade chief executive Egbert Laege, who is also a director of EEX, tells TW+.

The clearing house for freight paper trades will grow significantly in size by taking over most of rival LCH Clearnet’s dry bulk freight forward freight agreement (FFA) and option contracts. It is also moving from its iron ore and fuel oil origins into LNG derivatives, and hopes gas futures can act as a stepping stone to other tanker-based wet freight trades.

But although many of the more forward-thinking players in the bulk markets have adopted freight futures over the past 25 years, many more traditional ship operators have remained suspicious of trading in the market. Hedging is one thing, but some have been badly burnt when they have drifted into speculation.

“The stability of the underlying [physical shipping] market is very, very important but the more people that are convinced that this [the FFA] market is a fair indexation and you really can manage your risk exposures in it, the more participants will come in. And the more diverse the participants is what makes [for] healthy and efficient markets,” Laege says.

EEX purchased the US-based Nodal Exchange this year to give it a global spread. Then the Leipzig company struck a deal to pass LCH’s open positions in FFA and option contracts to its European Commodity Clearing (ECC) house by the end of 2017. EEX acquired a 52% stake in Cleartrade from John Banaszkiewicz’s Freight Investor Services in 2014.

Laege says it is by no means mandatory for shipowners to become involved in the derivatives markets, but he argues that the flexibility of options contracts, which are easy to buy into and exit, provide a good way of managing risk.

“The freight market is very cyclical, so if, for example, you [an owner] think you are at a good point in the cycle where a shortage [of capacity] is expected and your ships are right on time when prices are picking up, you may not want to hedge all the way through — maybe just the first years when you are not so sure when it starts to pick up.”

Freight remains a brokers’ market, he says, because they add a lot of value to structuring deals. “Clearing is what we [Cleartrade] offer as a value-add.

“We have been significantly growing our clearing business this year — it has more than doubled so far — but the LCH business is of a different size again. It will be a significant step up in our business.”

SGX says it has around a 50% market share of the freight derivatives clearing business.

Further expansion in shipping is planned, Laege says. “What we have in mind is to link our existing gas business with the global trade perspective, and enter the market with an LNG offering within the first semester of 2018. That is one step in that direction.”

Despite the ambition, weaknesses remain. LCH is pulling out of the market because it was said the traditional clearer found it difficult to compete against other big players and failed to find the right regulatory set-up.

At about the same time, the Baltic Exchange pulled the plug on its electronic FFA trading platform, Baltex, which had failed to gain traction since being set up in 2011, making losses of more than £3m ($4m) in its early days, despite claiming to have processed its one millionth block future by June 2017.

EEX began with power commodities in Europe and gradually expanded along the value chain, Laege says, with clients that were also exposed to risks on fuels such as gas or coal. “When you go into coal, you realise that maybe your risk is driven more by freight volatilities. And this is why we are here.”

But he adds: “Launching a contract is super easy. If you don’t have clients interested in it, you have won nothing. So it is always a combination of having the right client base and the adequate product.

“Our freight offering gives us an angle into the iron ore market, which is predominantly traded by Asian counterparts. That will give us a good starting point, as that market has similar structures as freight. It is very much a broking and cleared market where a diversity of clearing houses is appreciated. That will be the next step.

“The third step is that the freight and the iron ore communities will give a synergetic push to our fuel oil offering, as they are very linked. So as it becomes more used, we will have the gravity to expand our portfolio on the wet freight side.”

LNG is becoming a global trading market involving big energy suppliers and producers. Oversupply means that “suddenly this baby is traded. It serves as an alternative to pipeline gas. But it is also a shipping market and requires the skill sets to manage this.” Trading companies in LNG have not been involved in shipping before, but fuel oil traders have.

However, Laege adds: “The launch of further products on the wet freight side is very much dependent on the speed and progress that we make on the near-term product launches.”

SGX head of commodities William Chin also says: “As with iron ore/coal and dry bulk freight, there are significant overlaps with LNG and freight.” SGX is working with the Baltic to develop LNG freight indices, and looking at ways of simplifying the trading of tanker derivative products.

Uncertainties exist in the regulatory arena too. The Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, commonly referred to as MiFID II, comes into operation in the EU next year.

That creates complications for traders working across global markets — and of course freight is a global market.

Cleartrade is developing an offering for a platform linked to the ECC clearing house, but coming under Singaporean, not European, law. It aims to launch the product by the new year.

Laege says swaps have almost disappeared and options now take a large part of the market.

He describes FFAs as a direct derivative of the ship, but more focused on volatility than an option, which is the derivative of the FFA contract and has more flexibility to day-to-day changes in prices.

“Shipowners’ lack of trust can only go away when they see that the derivative FFA market is working as a very efficient instrument of risk-catching.

“Even if you are more inclined to a traditional business model where you build a ship and you sell the freight in a bilateral trade ahead, maybe the company you have sold to is using the FFA market and you can see that this is almost equivalent. You can trade all the tenures to get it done — and your shipbuilding financier is convinced about the certainty and stability of that market as well.

“Then I think we have added something very efficient to the wider economy, and that is the role of exchanges.”

Could freight futures be at a tipping point?

EEX’s move into freight futures, via Cleartrade, linking to its strengths in commodity derivatives, puts it firmly in competition with Singapore’s SGX, buyer this year of the Baltic Exchange.

The two exchanges share a vision that makes sense of perceived synergies between freight and bigger commodity paper trades, and are looking into LNG derivatives.

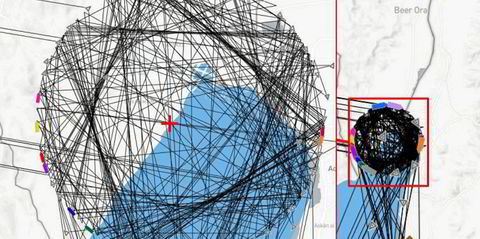

The freight futures market is estimated to involve 300 to 400 players of various kinds. It is fair to argue it has struggled to make much lasting headway, so can the latest synthesis work better?

Cleartrade holds one advantage: LCH Clearnet novated its contracts to EEX. But that does not mean all holders will move to it. LCH provided clearing for the Baltic Exchange’s Baltex on-screen trading system that was junked this year, and SGX says its FFA volumes have risen 79% from July to September this year.

The other major exchange FFA traders are most likely to consider is New York’s Nasdaq, which also has a strong presence in freight futures. The US marketplace plans to follow its rivals in getting closer to freight trades in Asia, where most of the physical action is, by registering in Singapore. SGX (obviously) and Clearnet are already registered there.

“Our ambition is to fulfill the role that LCH so far played in the market,” says Cleartrade chief executive Egbert Laege. He accepts that SGX and Nasdaq are strong competitors, but suggests EEX has a more client-focused approach.

SGX head of commodities William Chin says: “We are very much focused on growing the overall FFA market, through a widened approach that goes beyond traditional shipping interests to encompass cargo owners. We are seeing great success through this approach, given our existing strengths in related cargo derivatives, including iron ore and coking coal, and our deep network within this community.”

But the freight futures market has been here before.

It got going in the 1990s with the Baltic International Freight Futures Index known as Biffex, but shipping-based derivatives have never attracted the volumes of trades seen in established commodities markets, says Nikos Nomikos, professor of shipping finance at Cass Business School in London.

Oil futures trade at between 10 and 20 times the size of the physical markets but the best capesize paper options have secured is twice the size, at the peak of the physical freight market in 2007-08.

Tanker FFAs were once considered a potentially more sophisticated trade than dry cargo, but an attempt to tap into them by Norway’s Imarex with NOS Clearing at the turn of the century failed to make much traction. Nasdaq OMX acquired the remaining business for $40m in 2012.

Potential is seen in LNG derivatives, but Nomikos says that despite increased spot trading, a futures market will require established indices, sufficient participants, market transparency and volatility.

However, he agrees that freight futures could be at a tipping point with the greater visibility brought by the bigger exchanges. “It feels like we are back to where we were 10 to 12 years ago. To move beyond that the freight market needs to attract more outside capital to generate bigger volumes.” But non-shipping-related participation could also expose the shipping industry to wider risk factors, he says.