The sinking of a small Greek freighter off the Bahamas by an Italian submarine in 1942 shows how World War II got closer to the US mainland than many people imagine.

The torpedoing of the 25-year-old, 3,530-ton Cygnet, owned by the Goulandris Brothers, off the island of San Salvador is a compelling story illustrative of the global struggle, according to author Eric Wiberg.

Wiberg, who has written several histories of the U-boat war off the Bahamas, as well as other maritime books, writes about the incident from both sides in Swan Sinks.

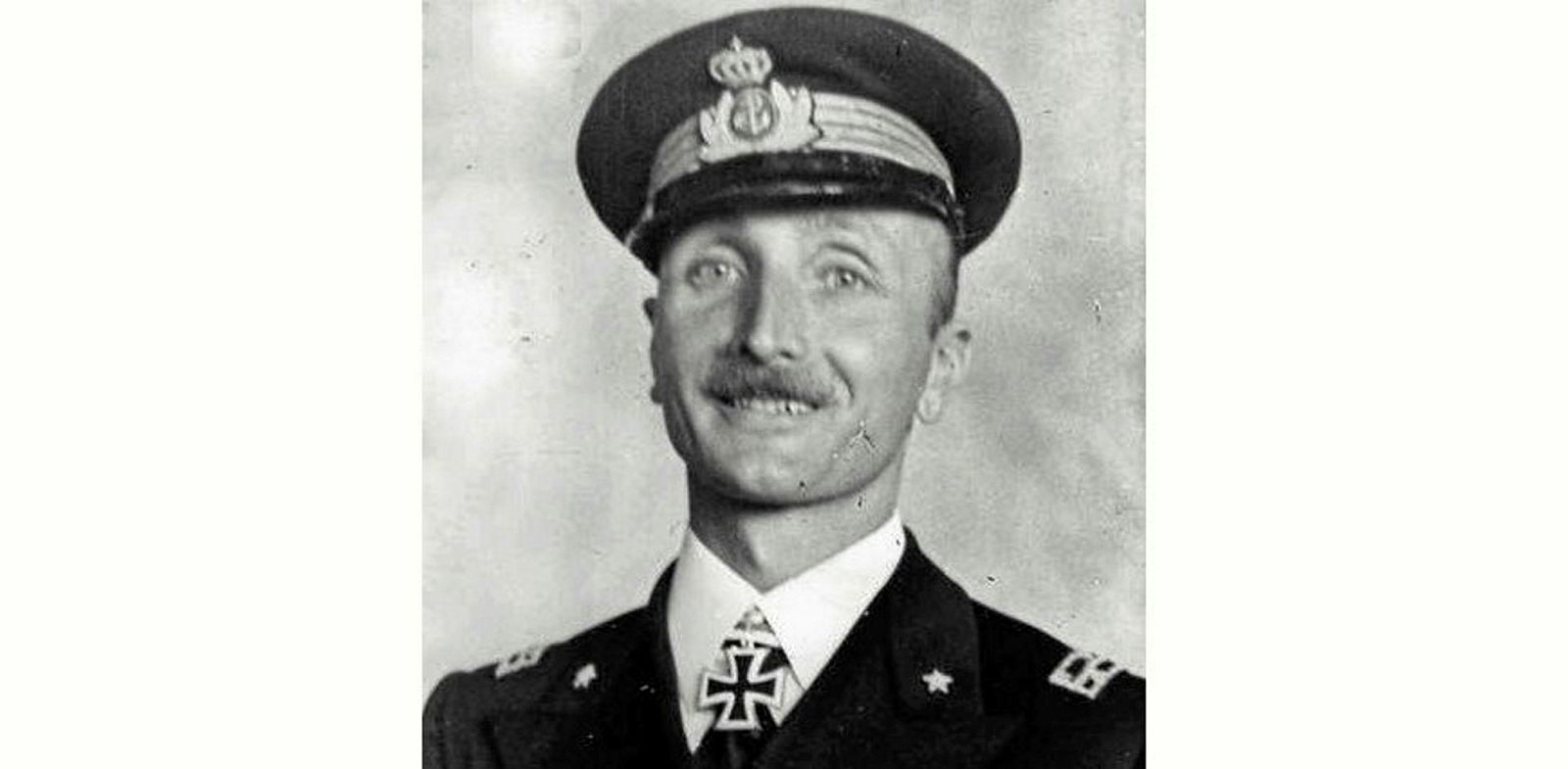

A diary kept by one of the Enrico Tazzoli’s crew, Antonio Maronari, notes that after the 84-metre (277ft) submarine had surfaced to finish off the Cygnet with shellfire, its commander responded to an American radio show which had boasted that Italian subs had not reached the US coast. “Tell the Americans it isn’t true. The Italian submarines have come here to sink their ships!” Commander Carlo Fecia di Cossato shouted in English to Cygnet crew in their lifeboats.

Eric Wiberg grew up in Nassau, Bahamas, before going to Boston College and skippering a 68ft sailing yacht from the Galapagos to New Zealand at 23. By the age of 25, he had relocated to Singapore and ran tankers for B+H Oceans for three years.

After obtaining degrees in maritime law and marine affairs, he relocated to the Stamford, Connecticut area, where, among other things, he was an executive recruiter for the shipping industry and sold subscriptions to TradeWinds, before moving to McAllister Towing as marketing manager in 2013.

Wiberg has written several maritime books, including Tanker Disasters, U-Boats in the Bahamas and U-Boats off Bermuda. He says the Goulandris family generously allowed him access to people and offices in the US, UK, Bahamas and Greece for the writing of Swan Sinks.

The submariners wished the Greek sailors good luck. The seafarers, who all got off the ship, waved back cheerfully — at least according to Maronari.

The Dutch-built, Panama-flag freighter, which had operated between Europe and South America for decades, was carrying bauxite from Georgetown, British Guiana, to Portland, Maine, on its final voyage. Its crew of 30 was led by Captain John Mamais.

At 4:48pm on 11 March, chief officer Antonios Falangas saw a torpedo emerge from beneath the ship after just missing. Moments later there was an explosion forward, by the number one hatch, as a second torpedo hit.

Chief engineer Constantinos Vlachakis, who was on deck, saw the heavy cargo hatch blown off and “a cloud of dust and debris rise several hundred feet with the explosion”. From the bridge, the captain and first officer watched in horror as a steam donkey engine used to raise and lower gangways was shattered.

Maronari wrote in his diary of the stricken ship’s last moments: “Suddenly the sky darkens. A red glow, followed by a piercing roar, broke the flow of our thoughts. Cygnet has jumped in the air, water has invaded the boilers, causing the explosion and then the greedy ocean swallows these other 4,784 tons.”

It took the Cygnet’s crew 10 hours to row the six miles (nearly 10km) to San Salvador, arriving at the dangerous reef line at 4am. Locals had witnessed the attack and a one-legged American by the name of AB Nairne came out in a dory with two others to lead the lifeboats through the reef.

The next day the crew sailed on an inter-island steamer to the capital, Nassau, to be met by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. They were also given a warm welcome by fellow Greeks from Kalymnos who had lived in the Bahamas since the late 1800s, when they had arrived for the sponge fishing trade.

The crew were eventually cleared by American consuls to go to the US, where they rejoined their employers in New York. Also heading for the US was a teenage Sidney Poitier, who been raised in the Bahamas. But Wiberg reports that the seafarers missed sharing the local freighter journey with the future Academy Award winner by a few days.

For most of the sailors, it would take until the war’s end before they were able to reunite with friends and family in Greece, and some would opt to stay in the US.