Dozens of ships could remain stuck in Ukraine’s ports because of seafarer shortages even after a deal was struck with Russia to restart grain exports, a crewing manager said on Monday.

The key problem is the continuing ban on domestic seafarers aged 18 to 60 from leaving Ukraine, said Henrik Jensen, the owner of Eastern Europe crew manager specialist Danica Maritime.

Jensen said overseas replacements will be unwilling to travel to a war zone following weekend missile strikes by Russian forces on the port city of Odesa.

“To get the ships moving again, we need the Ukrainian government to open up the seafarers to leave the country,” said Jensen, whose Germany-based company has 1,200 Ukrainians on its books.

“The Ukrainians are ready to fill these ships as soon as they give the green light.”

He said the authorities were concerned that a martial law waiver for seafarers could lead to false claims from other Ukrainian men desperate to leave the country.

A Turkey and United Nations-brokered deal on Friday last week prepared the way for sea corridors that would allow escorted convoys to resume grain exports from the three key Ukrainian ports of Odesa, Chernomorsk and Yuzhny.

The UN described it as a “de facto ceasefire” agreement while ships bring out the grain under escort to stave off a global food crisis.

The International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) said that 400 bulkers would be needed to bring the estimated 20m tonnes of grain out of the country.

The Ukrainian Seaports Authority has called for applications to join the convoys to export some of the 20m tonnes of grain to clear space in storage for Ukraine’s new harvests.

Ukraine said Russian missile strikes on Odesa at the weekend did not hit the port’s grain storage area and that plans to resume shipments were continuing. It was not immediately clear when the exports would restart.

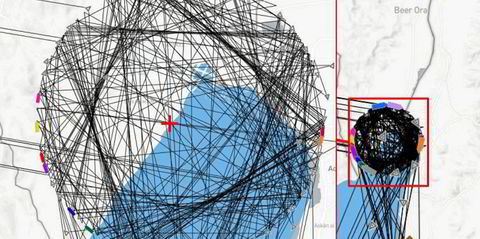

TradeWinds has identified some 50 non-Ukrainian or Russian ships of over 10,000 dwt currently stuck in ports.

ICS officials say total crew numbers have been cut from 2,000 to a skeleton of 450 for safety reasons but bring new problems of how to recrew the vessels.

“I don’t suppose too many want to come to a war zone,” said Jensen, who said he had already been approached by shipowners of vessels stranded in the ports for experienced seafarers.

He said that new crew would likely be brought overland from Romania or Poland to Odesa because of war-related travel restrictions.

Ukraine supplies about 5% of the 1.89m global seafaring workforce but the majority of them are trained officers.

The Seafarer Workforce Report of 2021, published by trade associations Bimco and the ICS, had already warned of a shortfall of about 26,000 officers over the next four years.

Kuba Szymanski, the secretary general of InterManager, which represents the ship-management industry, said he believed that any crew shortfall would be filled by non-Ukrainian seafarers.

He said there were no issues over crewing for ships travelling through piracy hotspots off the coasts of Nigeria and Somalia.

Issues still needed to be resolved over the safety of ships and the willingness of Russia to abide by the agreement.

But he added: “If the corridors are open, there will be ships and people who will go there.”

Crew transfers did not normally happen in Ukraine and the stranded vessels could be recrewed by seafarers arriving by ship from Istanbul, he said.