It has been said that Greek seafarers do not write, while those who do write about shipping are not seafarers.

But there are notable exceptions. Most Greeks are familiar with the poems of Nikos Kavvadias, who spent four decades on cargo ships. Put into song in 1979, four years after his death, his works still get radio time and sell well.

Performed by some of the country's best-known singers, his poems have become a cultural touchstone for the rugged life that tens of thousands of Greeks led at sea throughout the 20th century.

Kavvadias’ verses brim with unflinching accounts of knife fights, drug abuse, sexual adventure, disease, abandonment and a sheer longing for home.

They sometimes seem to be stretching belief, as in the story of a sailor who fled to an Eskimo settlement on the Aleutian Islands to escape a vendetta on Cephalonia.

However, such writings sound plausible when one looks at Kavvadias' personal history. A member of the Greek trading networks that spanned the globe well before World War I, he was born in Manchuria, the son of a Cephalonian supplier of Russia's czarist army.

His father was eventually arrested and went broke after the Bolsheviks took power in the October Revolution in 1917. The family was forced to return to Greece and Kavvadias became a sailor to support his family.

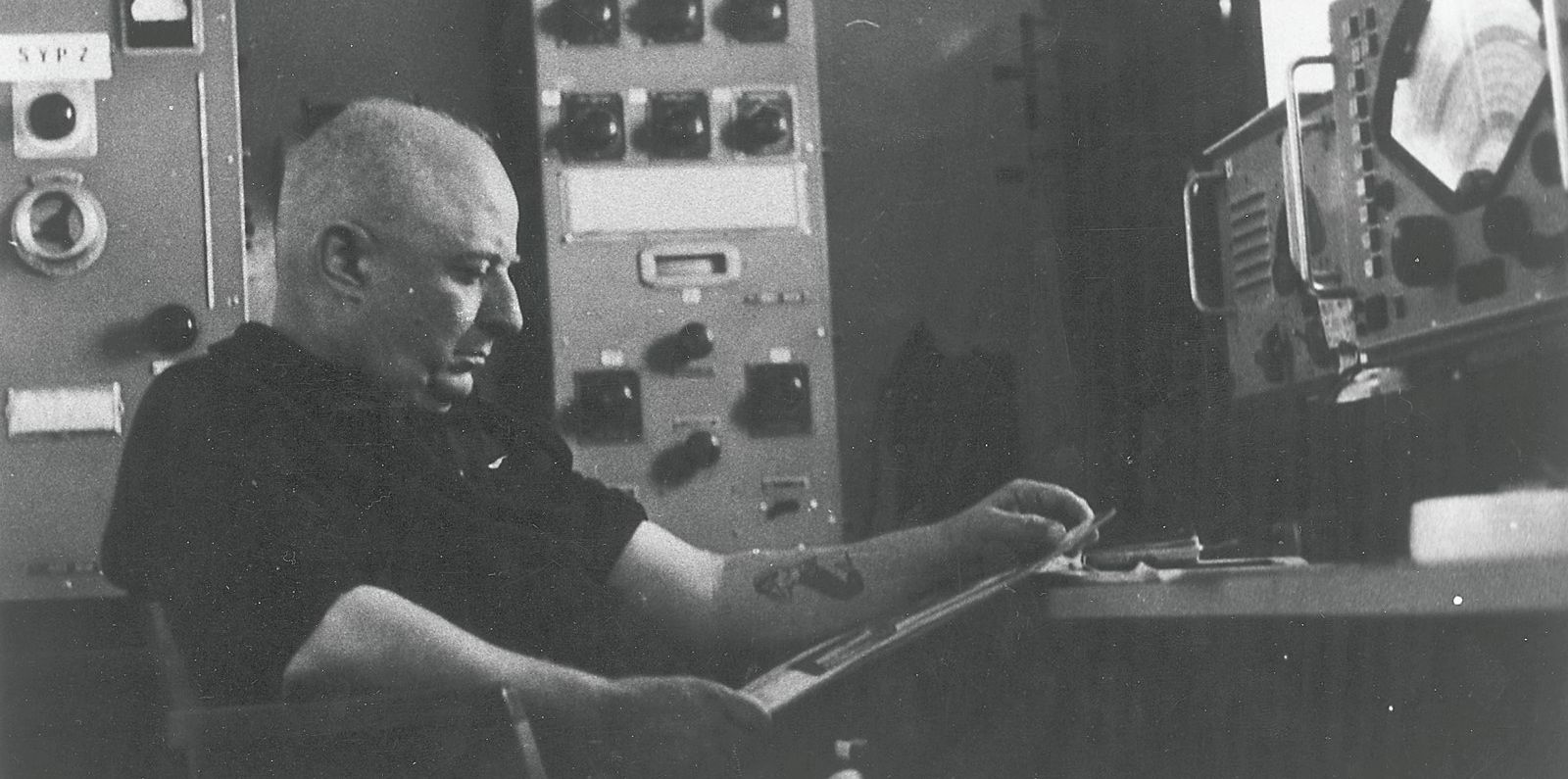

He initially planned to become a captain but he spent too much time travelling and writing, so he settled for radio officer instead.

Kavvadias recorded his maritime experiences and stories in a book, The Shift, or Vardia in Greek.

He suffered a stroke in Athens and died at the age of 65 in 1975.

Just a few months later came the death of another remarkable man of letters whose shipping background could not have been more different from Kavvadias'.

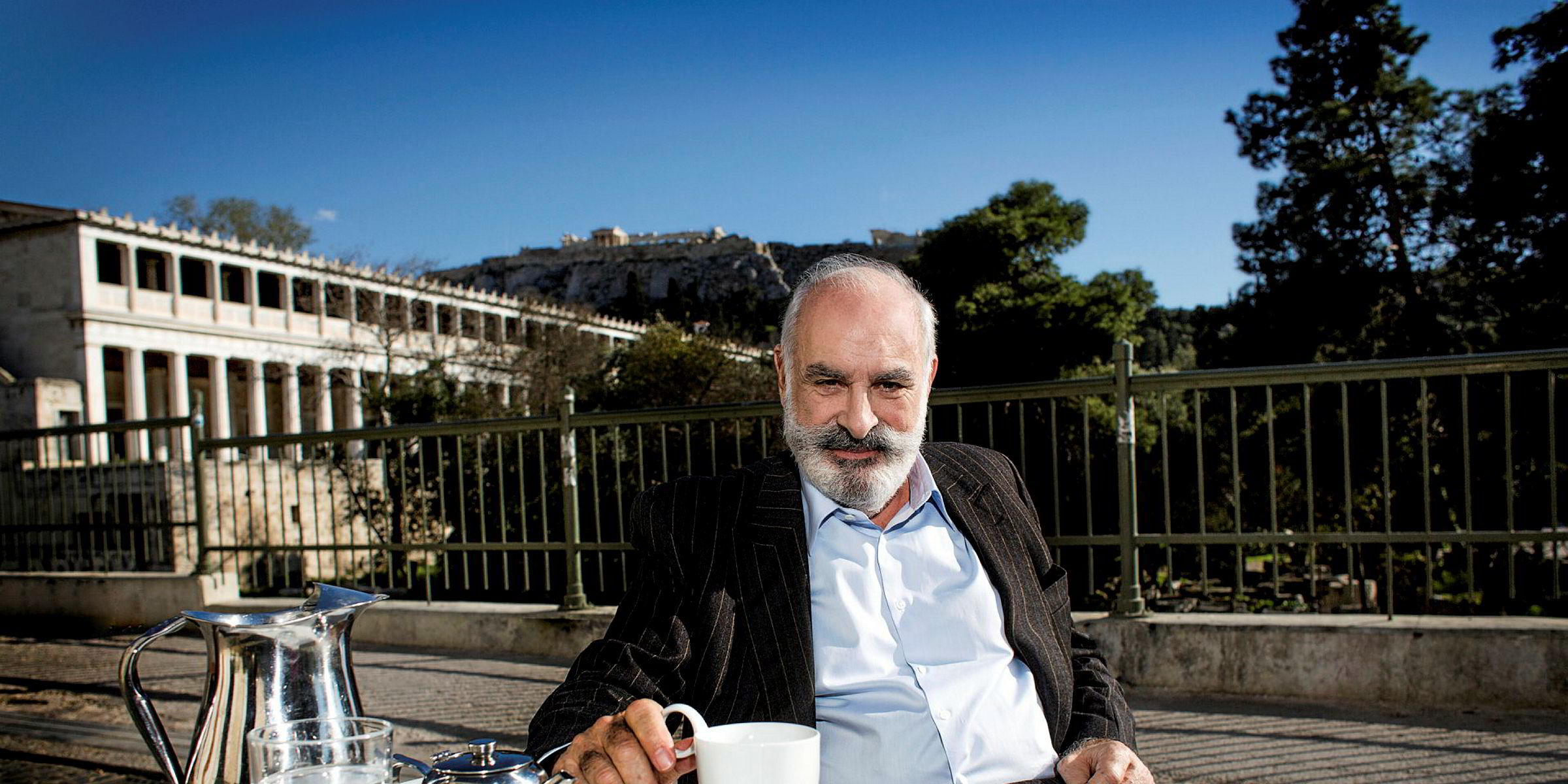

Andreas Embiricos was the scion of one of the wealthiest and most influential dynasties in Greek shipping history. Ηis father, Leonidas, was the first president of the Union of Greek Shipowners and the main shareholder in the country’s biggest ship-repair facility.

Greece's first surrealist

Young Andreas tried his hand in the family business twice — he quit both times.

At the heart of this was the breakdown in his relationship with his father. Not only did Andreas take his mother's side in his parents’ divorce, he became a standard bearer for ideas that his family and bourgeois society at large were dead set against: communism, surrealism and psychoanalysis.

Embiricos may have been ideologically opposed to capitalist shipping, but it was still a vessel that inspired him to write his flagship book.

The Great Eastern — a fictional account of the maiden voyage of one of the biggest steamships of the 19th century from Liverpool to New York — is the most controversial book in Greek literature.

A 2,100-page display of surrealist automatic writing, it is so full of explicit sexual, often pornographic, language that it was not published until 1990 — 15 years after Embiricos died at the age of 73.

Newspapers publishing excerpts from the book still risk incurring public prosecutors' wrath for offending public morals — as a local paper on the island of Andros, the Embiricos family’s cradle, found in 2002.

Embiricos conceived The Great Eastern as a subversive attack on 1950s conservative Athens society that had forced him to give up a psychoanalytic practice under the threat of lawsuits.

However, by that time, Embiricos had shifted position. A traumatic personal experience caused him to turn against communism — at least the version inspired by the Soviet Union.

Unimpressed by Embiricos' progressive credentials as a left-leaning surrealist, a band of communist insurgents operating in the turbulent weeks after the Nazis abandoned Greece in 1944 took him hostage as a suspected bourgeois agent and threatened to shoot him.

Embiricos only managed to escape after a tortuous foot march through the woods around Athens.

“If he hadn’t been taken hostage, The Great Eastern wouldn’t have become such an interminably long novel,” his son Leonidas reminisced in an interview.

This article is part of a series of stories looking back at the history of Greek shipping, on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the country's independence