If Prexit — the exit of private equity from public shipping company investments — were a baseball game, the process would likely be in the third or fourth of nine innings, a top investment banker reckons.

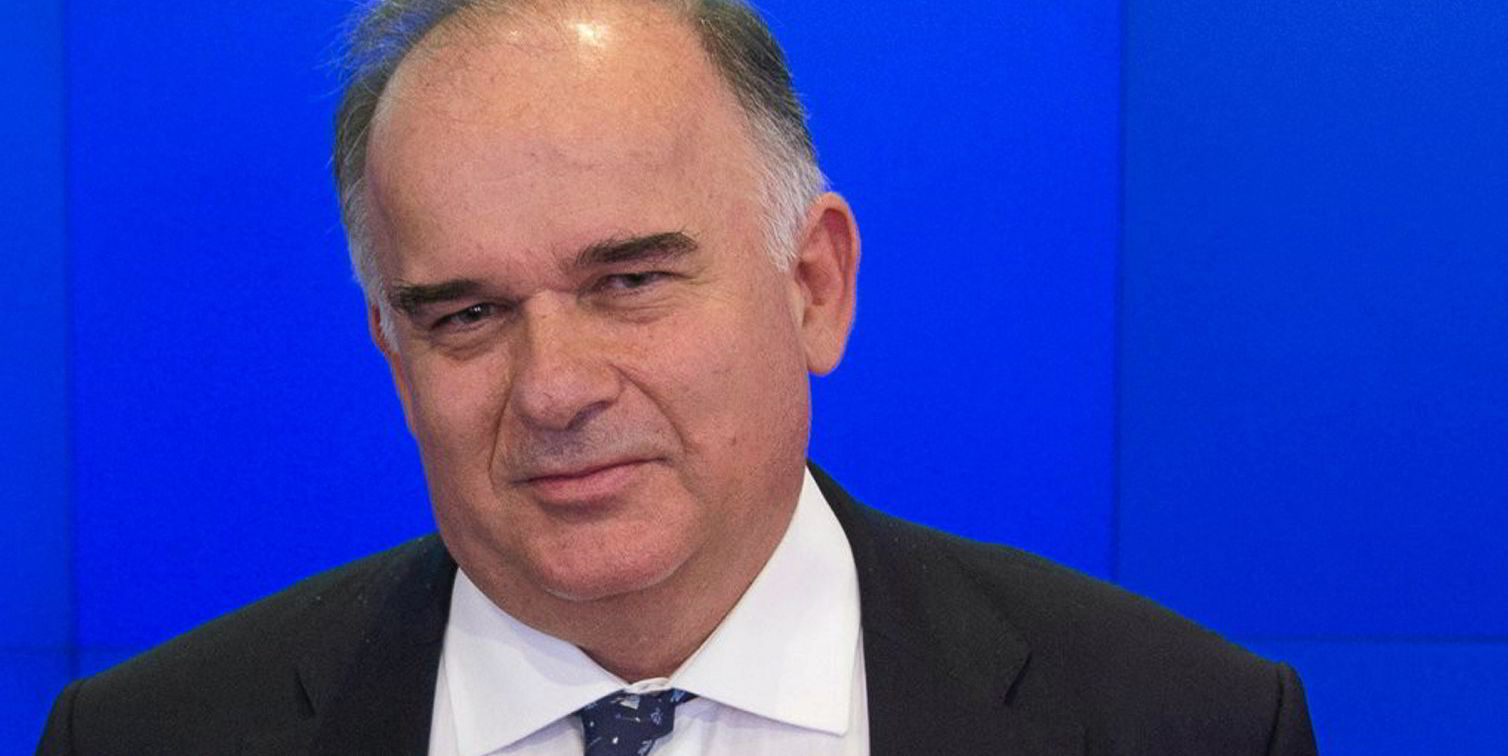

“We’re in the middle innings,” Jefferies shipping banker Douglas Mavrinac said. “There’s a lot that’s been transacted and a lot more to be transacted.”

Mavrinac’s baseball analogy might have been perfect for a warm summer day in New York, even if it was made virtually as Covid-19 forced the annual Marine Money week conference online.

And to take the comparison a bit further, it seems the Prexit game is also starting to be played by an expanding set of rules as demand for shipping shares grows among investors.

There are three different ways for private equity firms to cash out their investments, as explained by investment banker Chris Weyers of Stifel.

Shipping is increasingly seeing all three come into play.

Investors can simply sell shares into the market, as has happened with dry bulk firms Genco Shipping & Trading and Pangaea Logistics Solutions in the past several months.

They can sell a “bought” deal, as happened in May when Oaktree Capital Management sold a block of 10.6m shares to investment bank Morgan Stanley.

Or they can choose a “marketed” transaction as Oaktree did with 2.38m shares in the past week in a deal led by Morgan Stanley.

Previous marketed deals came last November, when US finance firm Cerberus Capital Management sold its entire 3.1m shares in Greece’s Danaos Corp, and 1 June when Israeli liner operator Zim saw backers including Deutsche Bank sell $320m-worth of shares.

In bought deals, underwriters take the risk in purchasing the shares for their own account at an agreed price, hoping to then resell them into the market.

In marketed deals, the banks act more like underwriters of an initial public offering, building an investor book at a market price and then giving the selling shareholder the choice of proceeding or not, as happened most recently with Morgan Stanley and Oaktree.

Increased liquidity in shipping stocks — which can be read asmore investor interest in a better freight environment — makes the marketed or bought block sales more feasible, Weyers said.

But all the activity does not necessarily reflect “smart money” getting out at the top, Mavrinac said.

“Many of the investors have been involved for a long period of time, in some cases longer than the funds anticipated. At times, they need to monetise the investment,” Mavrinac said.

“There’s a variety of motivations. It may not be because they want to sell or don’t believe in the duration of the cycle.”

But where such sales repeatedly see a company’s share price continue to rise going forward, new investors are increasingly attracted to take part, he said.

As one example, Cerberus Capital Management sold out of Danaos last November at $11 per share, bringing in gross proceeds of about $34.5m.

The stock was trading about $75 per share this week, meaning the same holding would be worth $235m.

About a month earlier, Greek shipowner George Economou cashed in 1.82m Danaos shares for about $15m. That stake today would be worth roughly $136m.

In that case, Danaos used its own share repurchase programme to take back the shares.

Another example came in January, when one of Genco’s largest holders — hedge fund Strategic Value Partners — sold 6.1m shares at just over $8 each, bringing in total proceeds of roughly $50m.

Genco was trading near $20 recently, making the same holding worth more than $120m.

“There likely will be more deals — we haven’t seen a concern with absorbing all the air out of the room,” Mavrinac said.

“When you’re able to show the investor that ‘the last time you bought at this price, and now it’s up here,' well, success begets success.”

While bankers spoke during the forum about long-only institutional investors starting to come back into shipping across operating sectors, that has not been the dominant source of buying here, Mavrinac said.

“We’re seeing more institutional participants, but it’s not the majority,” he said.

“The others are liquidity providers, also called ‘flippers”, who are looking to make a quick profit.”