Ferry and container liner operations have been identified as the most effective routes on which to develop green shipping corridors, a report from the Getting to Zero Coalition has determined.

The coalition, an offshoot of the Global Maritime Forum, said analysis of the original Clydebank group of countries that signed up to the corridors at COP26 in Glasgow last year showed that most potential centres on the ferry sector.

Ropax ferries accounted for 11% of traffic and ro-ro vessels 7.4%, container ships 7.4% and bulk carriers 6.2%, said the Green Shipping Corridors: Opportunity Identification report.

It identified three case studies — two shorthaul routes for ferries and one long-range for container ships.

Setting out details of the routes, it said the next steps would be to develop analysis to help stakeholders evaluate their potential.

Oita was identified as the head port of a northern cluster around Kyushu Island in south Japan, where five ro-ro vessels and one bulker operate exclusively between ports.

Bilateral services on the Oita to Osaka route are covered by four of the ro-ros travelling a median voyage distance of 215 nautical miles (398 km).

They have a cumulative demand of 49,000 tonnes of heavy fuel oil equivalent (HFOe) per year, which is equivalent to 16,200 tonnes of hydrogen by mass that needs to be produced.

Hydrogen has a higher gravimetric energy density — per unit mass — than HFO but a lower volumetric energy density, meaning it takes up more space in storage or ships’ tanks.

The potential business case for a plant near Oita for green hydrogen or ammonia production, or a scalable zero-emission fuels import terminal/dedicated infrastructure, could be strengthened by including other shipping activity in the area.

Thirteen vessels — five LNG carriers, three ferry ropaxes, two general cargo ships, one bulker, one vehicle carrier and one chemical tanker — were identified as operating exclusively between the wider clusters of Oita, Mizushima, Osaka and Tokyo.

The energy supply required to decarbonise their activity was estimated at 70,450 tonnes of HFOe per year or 22,900 tonnes of hydrogen, with calls within 60km of the lead ports.

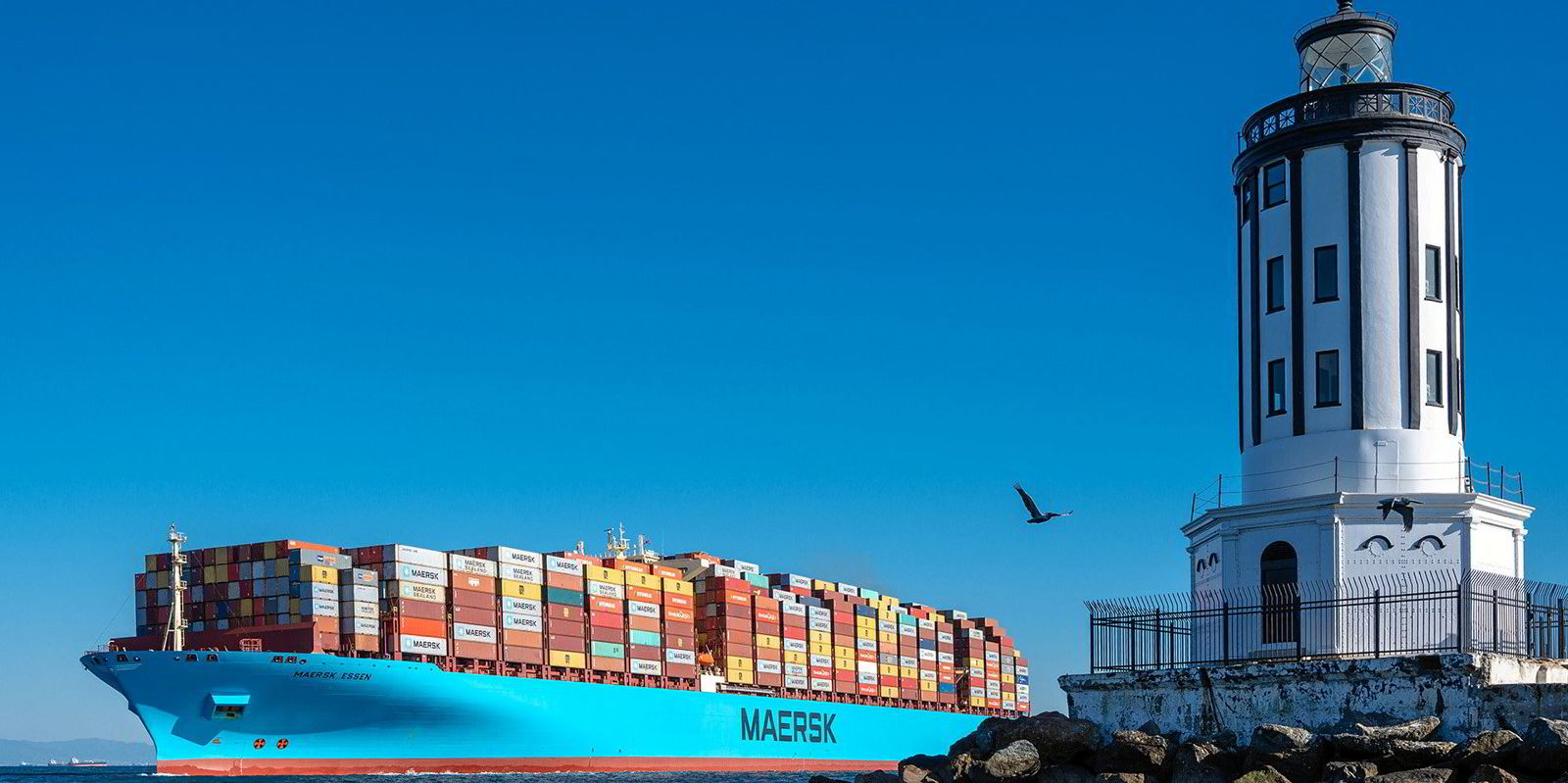

The report also considered a long-range transpacific green corridor for container ships between Osaka, Nagoya and Tokyo, and the US west coast ports of Oakland and Long Beach operated by five vessels with an average capacity of 4,500 teu.

They combine yearly fuel consumption of around 114,000 tonnes of HFOe per year and limit their stops to the main ports, reducing the need for local distribution logistics. Hydrogen production translates to 37,100 tonnes per year.

Voyage distance is helpful to define storage capacity on board and mean speed at sea to avoid over-dimensioning main engines, the report said. Time at port supports in planning logistics and provisioning facilities such as bunkering or battery charging.

“These factors are essential to estimating the costs of decarbonising the route,” it said, and understanding them can help identify the potential to reduce costs.

The final route considered was a green corridor across the North Sea between Immingham in eastern England and Hoek van Holland at the entry point to Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

Four ferries operated throughout 2018 with an estimated demand of 42,800 tonnes of HFOe — equating to 13,900 tonnes of hydrogen. Voyage distances were 200 to 230 nautical miles.

An advantage was the route does not involve calling at other ports and so would not require a local distribution network, only bunkering facilities at either, or both, of the main terminal hubs.

Three of the vessels were ropaxes. The smallest was a cargo-focused ro-ro. The ropaxes spent 10 to 12 hours in port, while the ro-ro stayed an average of 14 hours per stop, meaning it performed about 40 fewer voyages per year.

Three of them had annual fuel consumption of around 10,000 tonnes of HFOe, and the fourth about 21,000 tonnes due to a larger power output of its main engine.

The report asked: “Would it be better to set up the corridor, starting only with the biggest vessel in the route, given that it may be approaching decommissioning time due to its age? Or would it be better to start with one or both of the smaller ropaxes?”

Technical specifications suggest the two smaller ships are sisters, so there could be a gain in the economies of scale of two vessels instead of one, it said.