The final section of the 7,700-ceu Golden Ray (built 2017) is being hoisted ashore two years after it catastrophically grounded at the US Port of Brunswick in Georgia, and 12 months after the first cut was made to dismantle the wreck.

Over the two years, salvage, environmental protection and wreck-removal operations have run up an eye-watering $840m bill.

The final tally will be handled through the International Group of P&I Clubs, and will be met mostly from its reinsurance programme.

There have inevitably been questions over whether the job could have been done more quickly and cheaply.

Matthew Moore, global claims director at North P&I Club — who handled the Golden Ray claim — said completion of the job shows the International Group, and the reinsurance system, can effectively handle the most complex of casualties.

Big challenge

"We knew from early on it was going to be a big challenge," Moore said. "I think the outcome has been a success for the member and club, the International Group and its reinsurers.

"It comes down to the team that was assembled. In this case, we had a great team with what T&T Salvage were able to offer, along with the Unified Command, the state and the US Coast Guard [USCG]."

Although the casualty ran for two years, Moore said the wreck removal actually took only 12 months, which was in line with the initial plan.

The schedule was kept despite contending with the hurricane season and — most unexpectedly of all — the global Covid-19 pandemic.

While costs might appear to have run away, the wreck removal, which accounts for about half the bill, was contracted at a fixed cost.

It was the time-bound environmental costs that varied.

Moore added that the decision to select Texas firm T&T Salvage came down to the strength of its technical solution, and that North P&I Club was not pressured into selecting a US firm.

September 2019: The 7,700-ceu car carrier Golden Ray (built 2017) grounds at the Port of Brunswick. All crew members are saved in a dramatic rescue operation. Work gets underway to take fuel off the ship.

October 2019: The US Coast Guard determines the vessel cannot be refloated and will have to be cut up and demolished.

January 2020: T&T Salvage is awarded the wreck-removal contract.

July 2020: Salvage operations are suspended because of a Covid-19 outbreak.

November 2020: T&T Salvage makes the first cut into the Golden Ray wreck.

October 2021: The final section of the Golden Ray is loaded onto the VB 10,000 heavylift ship for removal.

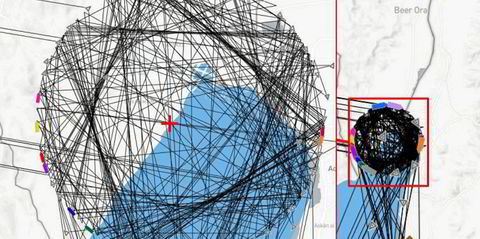

T&T Salvage proposed cutting the ship into eight large sections and carrying away each unit in a heavylift catamaran, VB 10,000, which was also used as a saw to cut the ship.

“T&T’s methodology was quite innovative,” Moore said. “Bringing in the VB 10,000 and cutting the ship into eight slices and lifting those slices, with cars in them, attracted us because it was far cleaner than cutting the ship up into small sections and having to remove the cars individually.”

Time and money

But could an early refloating of the vessel after it initially grounded also have saved time and money?

Moore pointed out that structural analysis of the wreck showed that there was not enough strength in the hull to withstand being pulled up. The ship had also foundered because of stability issues, and there was no guarantee the hull would not capsize again even if it could be righted.

North P&I worked with the local Unified Command response and USCG to ensure the operation was carried out within the strict requirements of the Oil Pollution Act of 1990.

Moore said the North P&I Club was on the same page as the local authorities when it came to protecting the environment.

Reasonable and proportionate

“The Unified Command was very helpful, and the demands that were made were absolutely reasonable and proportionate,” Moore said.

“There was an absolute common purpose in terms of the objectives — firstly protection of life, and the environment, to keep the port trading and to deal with the obvious issues of the property.”

A costly environmental protection fence that was constructed was also a necessary requirement to control the potential environmental impact of the wreck-removal job.

The Unified Command played a role in bringing all the stakeholders involved together. Town hall meetings helped keep the local community informed of the developments and engaged in the process.

As the operation wraps up, Moore said the project should be viewed as an example of how the P&I industry, and its reinsurers, are there to provide expertise and financial resources that can cope with the most catastrophic of shipping casualties.

"It can be easy to underestimate the technical challenges of taking a ship apart in a tidal seaway," Moore said.

“While it does take time, and there are time-bound costs, the key thing is that the job gets done, and that there is funding in place for it — and, in this case, the industry has done what is required of it.”