Bus passengers as far apart as Beijing, Barcelona and Aberdeen may be unaware they have been participating for years in trials to test the feasibility of hydrogen fuel cells in public transport.

The technology, which offers a cleaner and more efficient source of power, is now spreading to shipping as ports, just like congested cities, apply pressure to cut vessel emissions.

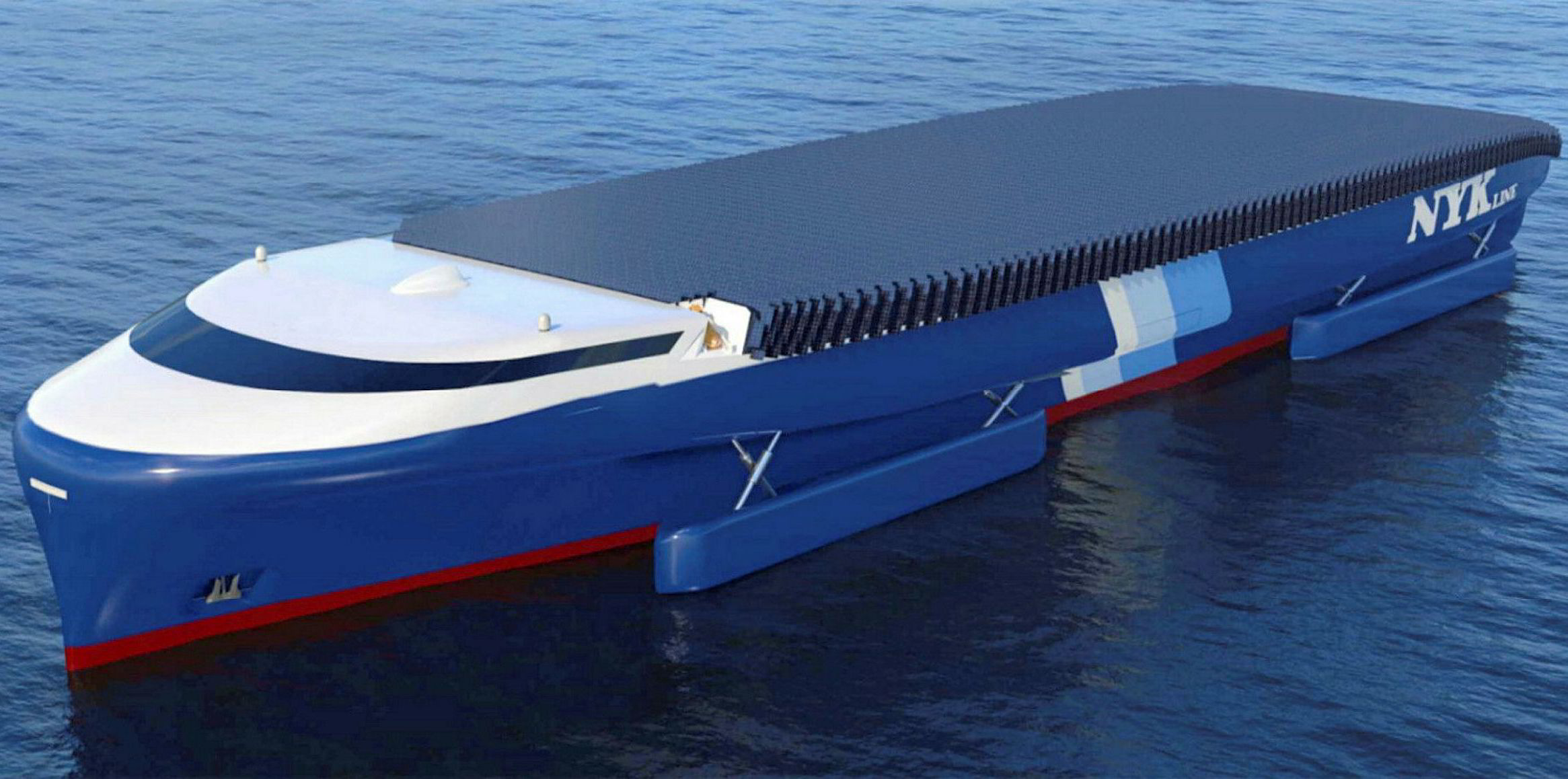

More distant but also feasible is upscaling fuel cells from the current focus on auxiliaries to larger MW systems for the actual propulsion of seagoing tonnage. Vessel designs are being developed by companies such as NYK Line and Viking Ocean Cruises.

The last two years have seen a surge of interest from fuel cell manufacturers looking to gain a foothold in the maritime market, driven partly by the interest of cruiseship operators.

Norway’s Moss Maritime and Japan's Kawasaki Heavy Industries are even developing bunker and longer-haul vessels, respectively, for carrying liquid hydrogen to meet expected demand as the technology takes off.

Fuel cells convert chemical energy stored in the fuel directly into electrical and thermal energy by electrochemical oxidation. NOx, SOx and particulate matter emissions can be eliminated to almost zero.

Classification society DNV GL says mass production of fuel cells is expected beyond 2022, bringing costs down to competitive levels. But only small maritime fuel cell applications with an electrical output of up to 100kW are currently in operation.

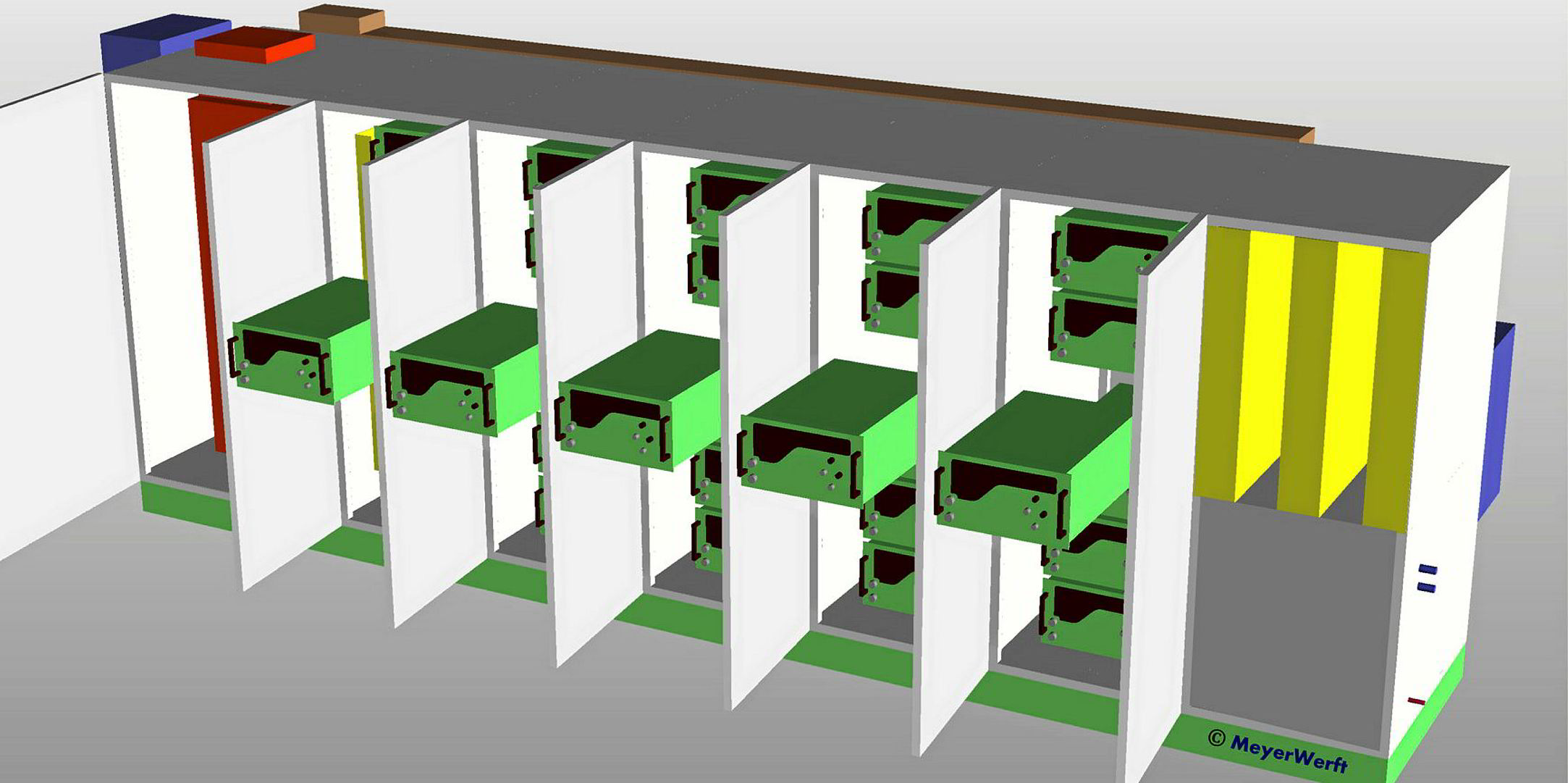

Much of the research is taking place in Germany following initiatives by cruiseship builder Meyer Werft and industrial giant ThyssenKrupp, the former owner of the Blohm+Voss shipyard in Hamburg.

They are part of the e4ships consortium involving other familiar names such as DNV GL, Flensburger Schiffbau-Gesellschaft and Lurssen shipyard, as well as equipment suppliers.

DNV GL claims in an assessment of alternative fuels that e4ships’ projects, aiming for a market launch in 2022, are the most advanced in terms of future commercial applications.

Coordinating the projects is Hamburg-based hySolutions, a public-private partnership working mostly for its partners, including Hamburger Hochbahn, the public transport operator in the port city.

Heinrich Klingenberg, general manager of hySolutions, outlined for TradeWinds the key maritime projects of the partly publicly-financed e4ships and his views on future potential applications at a time when the shipping industry faces the IMO challenge of a 40% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030.

One project — the Meyer Werft-led Pa-X-ell — is using Viking Line’s 2,500-passenger ropax Mariella (built 1985), which operates between Helsinki and Stockholm, to test methanol-fuelled, high-temperature proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells.

Those tests include evaluating the impact on fuel cells, especially from salt water, salty air and movement of the ship, particularly the effect on energy efficiency.

Klingenberg says fuel cell efficiency achieved so far has been good, although a new test project has already started that is aimed at having more efficient technology for maritime testing in around two years' time.

The emphasis of such projects so far has been on providing vessels with combined onboard heat and power (CHP), not the main propulsion where large seagoing vessels require machine output — in the case of the 183,900-gt cruiseship AIDAnova (built 2018) — of 61.7MW.

ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems is leading the so-called SchIBZ project consortium — part of e4ships — using road-quality, low-sulphur diesel to develop a hybrid fuel cell system for seagoing ships and having a power capacity of 50 to 500kW.

The project has tested a 50kW system, built in a container, on the 6,400-dwt general cargoship Forester (built 1996).

However, Meyer Werft is also heading up another project, RiverCell. It is designed for cruise vessels on inland waterways, where the brief is provision of fuel cell energy for the full power train.

RiverCell is still at the laboratory stage, but the intention is to install the system on a river cruiseship within maybe two years.

Once again, methanol is being used but Klingenberg says e4ships’ ambition is a larger variety of fuels, including LNG and low-flash-point diesel.

While still too expensive for the car makers, the cost of PEM fuel cells has dropped to a level that is attractive for ship applications

DNV GL

However, he does not expect to see fuel cells being used for the full power train of large oceangoing ships for probably another five to seven years.

In the foreseeable future, e4ships is working on employing 1MW units placed in segments in several parts of a vessel.

Smaller fuel cells supplying energy for hotel requirements, navigation systems and other onboard purposes will come sooner, with various companies including cruise giant Carnival Corp interested in such applications within four or five years.

Cruiseships are prime customers, especially given the high hotel power requirement and widespread adoption on newbuildings of LNG, which can be used both for the generator sets of the main power train and fuel cells for CHP. Fuel cells combined with electric motors are also virtually silent and vibration free.

Klingenberg says fuel cells are probably around twice as expensive as a conventional system at the moment, but the gap will close once online production brings economies of scale.

DNV GL’s alternative fuels study reported current fuel cells cost between $3,000 and $4,500 per kW of installed electrical power.

But ongoing developments aim to reduce this by up to $1,000 per kW by 2022 and make them competitive with modern diesel engine installations.

“While still too expensive for the car makers, the cost of PEM fuel cells has dropped to a level that is attractive for ship applications,” DNV GL said.

It says operational costs will be competitive when:

* Fuel cells are as durable as combustion engines until requiring a general overhaul;

* Cost and time of a fuel cell exchange is the same as general engine overhauls;

* Primary fuel prices are competitive with marine gasoil (MGO).

Fuel cells may also require less maintenance than conventional combustion engines and turbines.

In the Safe Return to Port regulation, subdividing say a 5kW system into 1kW units means it is easy to switch between them, increasing the level of redundancy.

Klingenberg says a problem with scaling up the technology is establishing production lines, because fuel cells are currently individually handmade.

He adds that fuel cells are around 60% energy efficient compared with conventional systems of 40% to 50%, but they still need to improve.

Lars Langfeldt, senior project engineer at DNV GL-Maritime and the class society’s project manager in the e4ships consortium, says Meyer Werft is planning larger applications of around 200kW for its inland river cruiser project, and is targeting even bigger systems for cruiseships by 2021.

DNV GL has identified the three “most promising fuel cell technologies for maritime use” as solid oxide, PEMs and high-temperature PEMs.

Jennifer Kreissel of hySolutions is in overall charge of e4ships’ projects.