Lightning never strikes the same place twice, as the saying goes, but the chances appear to be doubled in the world’s major shipping lanes — all because of marine fuel.

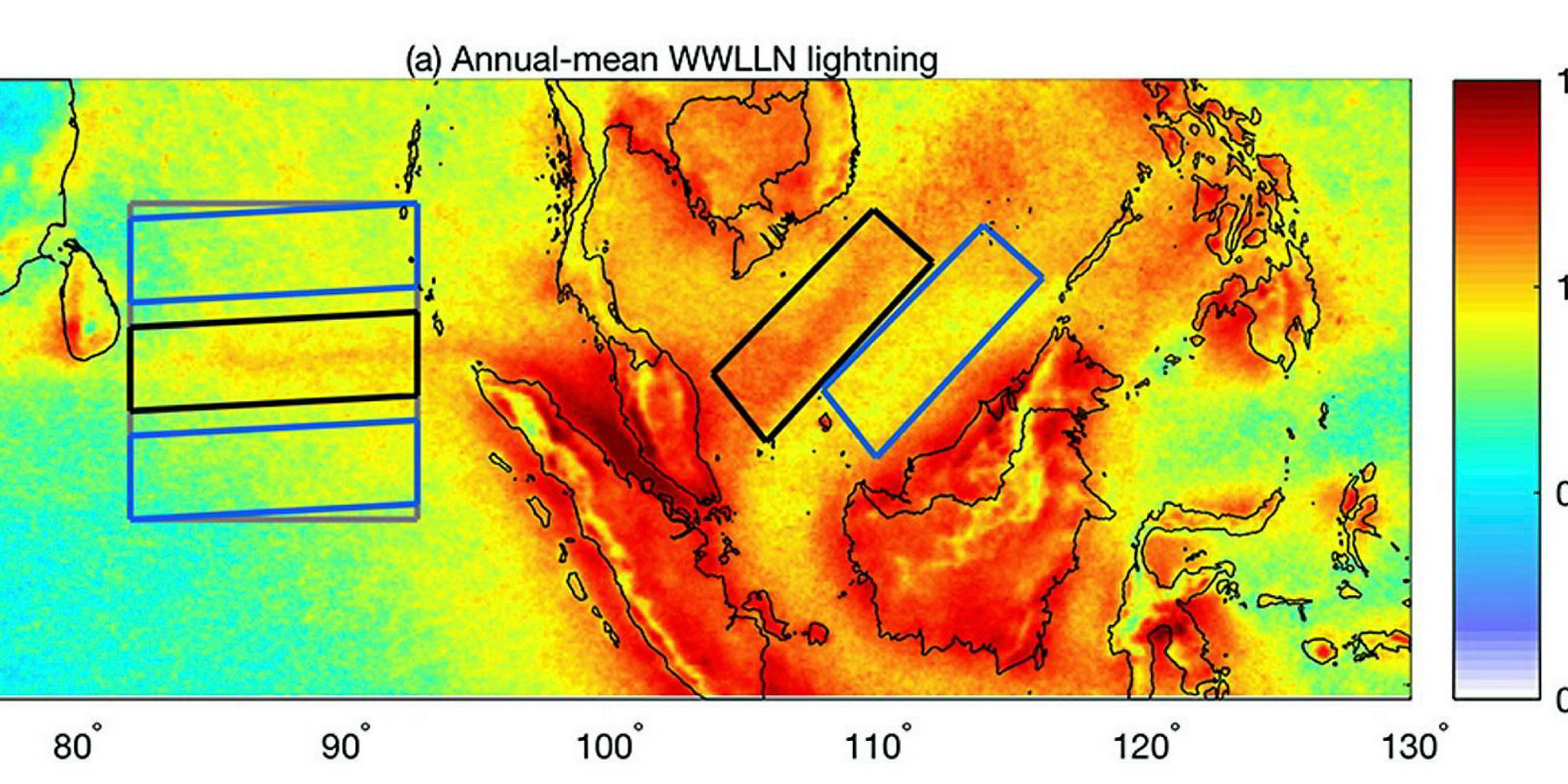

The Indian Ocean and South China Sea have been proven to have lightning density increased by a factor of two directly over major shipping lanes, according to a study by scientists at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Lightning is following the angular path of vessels and occurs twice as often as in adjacent areas with the same weather conditions, says Professor Joel Thornton and his team in the university’s department of atmospheric science.

The intuitive On Watch reader is likely to immediately think, “Of course, this is happening because ships are giant steel structures that are massive lightning rods on the extremely flat, wide-open spaces of the ocean. Right?”

Well, that is just not plausible, says Thornton. The vessels are spread out to begin with and the strikes are mainly hitting the area, not the ships. And, again, the density of hits “cannot be explained by meteorological factors, such as winds or the temperature structure of the atmosphere”.

Thornton and his crew believe that marine fuel — or actually the high-sulphur particulate matter spewing from many ships — is the most likely culprit.

“Lightning results from strong storms lifting cloud drops to high altitudes where freezing occurs and collisions between drops, graupel, and ice crystals lead to electrification,” they wrote.

“We conclude that the lightning enhancement stems from aerosol particles emitted in the exhaust of ships travelling along these routes.

“These particles act as the nuclei on which cloud drops form and can change the development of storms, allowing more cloud water to be transported to high altitudes, where electrification of the storm produces lightning.”

Thornton says some obvious major concerns are the harm to human life and the global economy from these intensified storms caused by marine pollution.

The evidence for Thornton’s conclusion comes from 12 years of high-resolution data collected by the World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN).

Led by Professor Robert Holzworth at the same university in Seattle, the WWLLN is a cooperation of 46 universities and scientific institutes around the world.

Thornton’s paper, published in the scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters, evaluated lightning strikes that have been recorded by at least five sensors from partners in the network.

The team dealt with 1.5 billion strikes in the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. Heat maps show a heavy density of strikes especially in the shipping lane from the south of Sri Lanka to the northern Strait of Malacca and down to Singapore, as well as from Singapore to western Malaysia.

One clear test of whether Thornton’s research is right will be the looming change in marine fuel, reducing sulphur content to 0.5% from 1 January 2020.