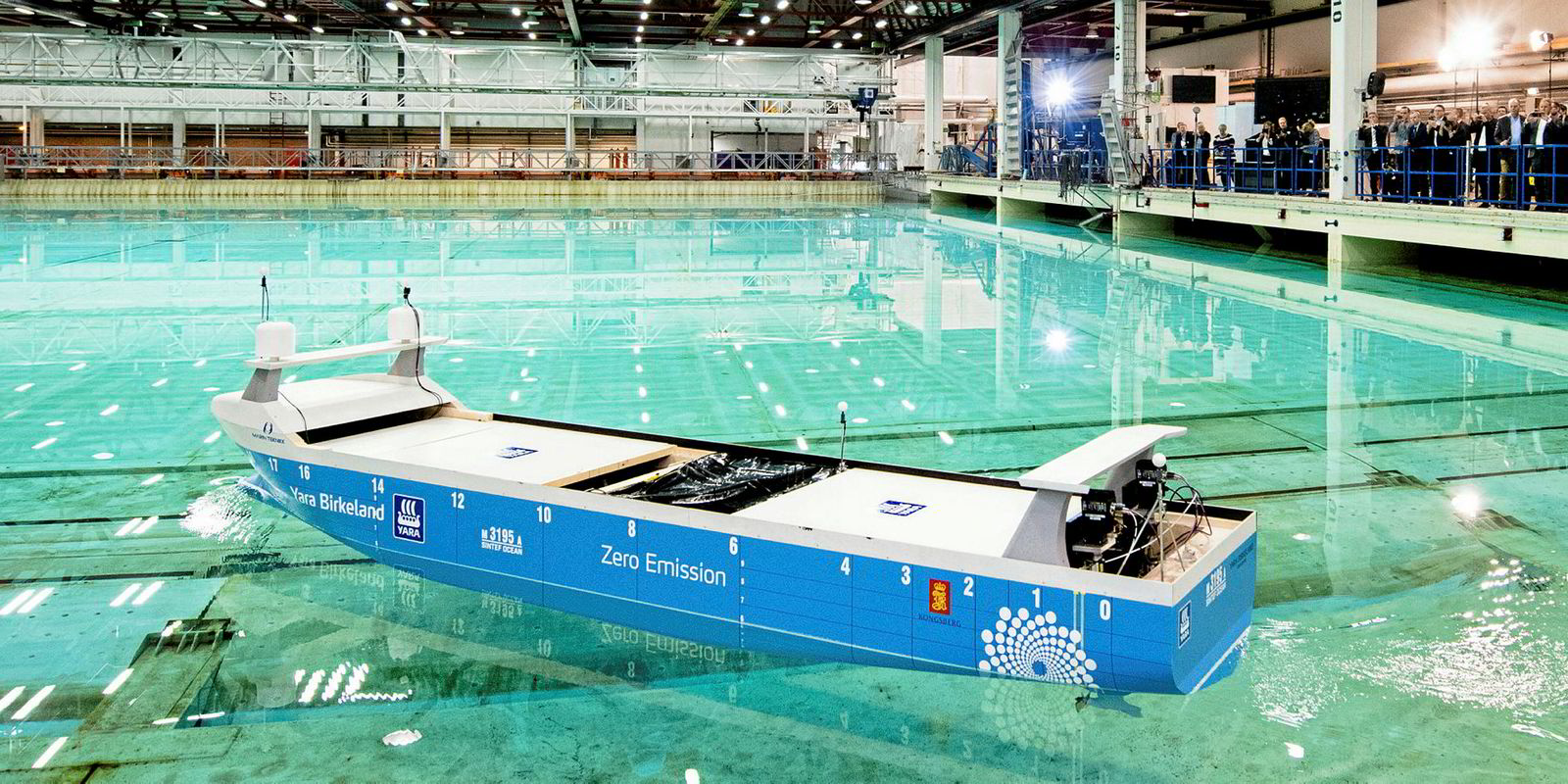

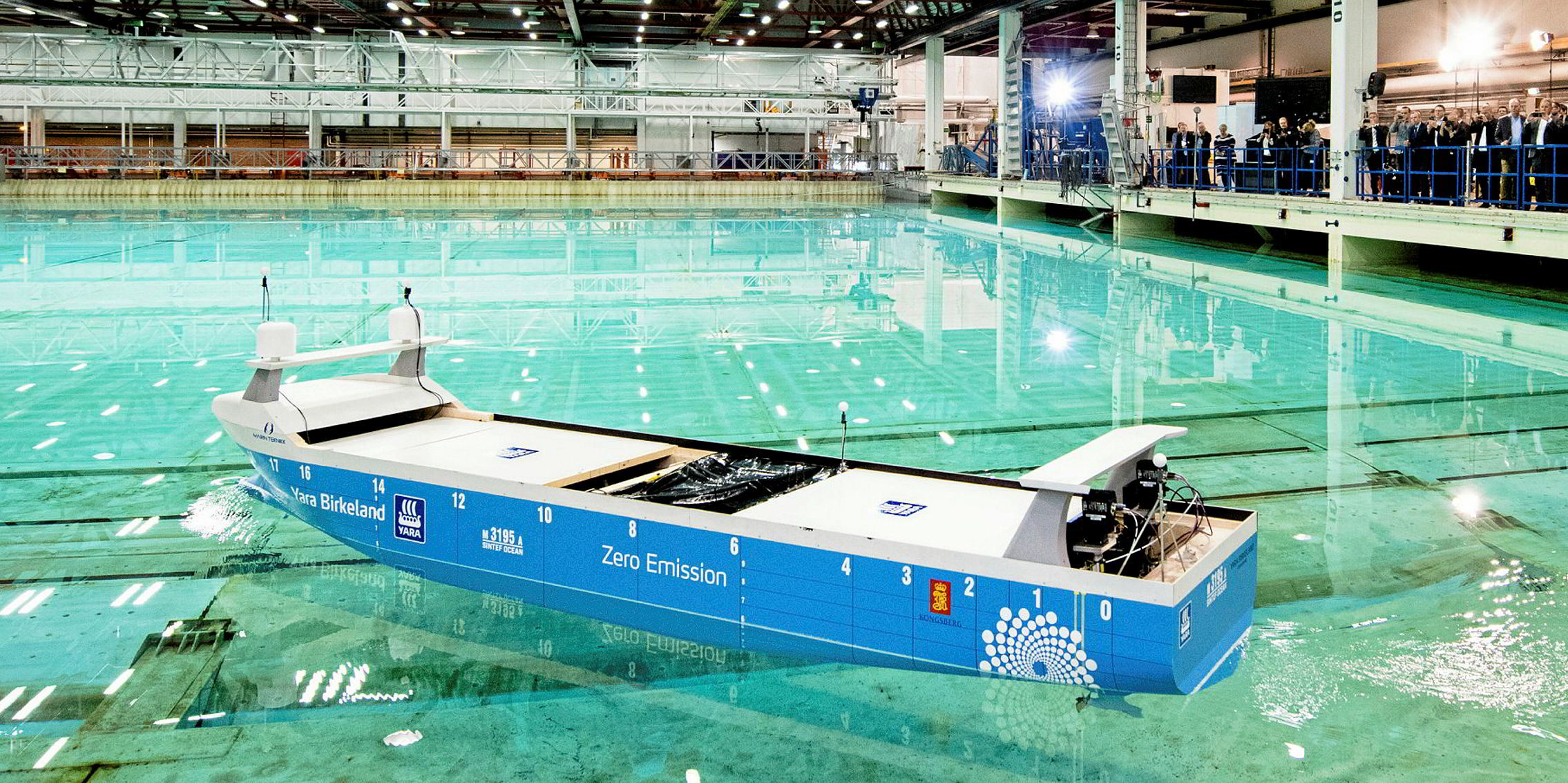

If it were a typical newbuilding, the Yara Birkeland would be christened, delivered and start work.

But the containership, a joint project between Norway's Yara International and Kongsberg, is anything but typical.

We believe that we will receive approval to sail Yara Birkeland without crew in 2022 and then have a unmanned autonomous ship in operation

Bjorn Tore Orvik

The world’s first zero emissions, fully automated cargoship is under construction now, on track for testing later this year and due to be completed in 2020 before making the transition to automation.

Regulatory concerns

And while the ship might be ready for work — it is intended for the domestic trade in Norway with the hope it will eliminate 40,000 truck trips annually — the country's shipping regulations may not be.

“I think we have very good collaboration with the authorities,” says Bjorn Tore Orvik, chief executive of joint venture Yara Birkeland AS, who adds that regulators want to make sure the autonomous ship is as safe as manned vessels.

“We believe that we will receive approval to sail Yara Birkeland without crew in 2022 and then have an unmanned autonomous ship in operation.”

Autonomous shipping writ large could change the face of shipping — and soon, thanks to projects like the Yara Birkeland. But before it can, regulators, the industry and the technologists behind these projects have plenty of details to work out.

Norway, although it signed a deal in the autumn to work out legal and regulatory frameworks, is not the only place where rules need to be hashed out.

The IMO started looking at autonomous shipping in December, with a scoping exercise at its 100th session. The United Nations-backed agency discussed developing guidelines for trials and standards with an eye to completion in 2020 and rules further down the line.

IMO scoping exercise

Without IMO rules in place, crew-less ships cannot yet crisscross the earth’s oceans.

“I think undoubtedly it’s a good thing that the regulations don’t allow it to be rolled out without significant prior thought about how it could be done safely,” says Christian Matthews, the head of maritime technology at Liverpool John Moores University.

He says the current system is shaping up to be one where autonomous technology can be developed and tested domestically. The kinks would be worked out there before the IMO gives the go ahead for the technology to be deployed in the international trades.

For example, he says, the UK rolled out rules that limit autonomy to ships 24 metres in length and Singapore is investigating autonomous tugs.

“I think that’s a sensible approach,” Matthews says.Other issues are not as easily ironed out and can veer into the theoretical.

Without a crew, autonomous ships can go without living quarters. But the IMO’s international Safety of Life at Sea (Solas) convention requires ships to be able to pick up survivors of sunken vessels. Another Solas violation would be stacking containers so high that they block the view from the bridge, which experts say should be a possibility given humans will not be at the helm of the ship.

What happens to the people who aren’t crewing the ships in the future?

Christian Matthews

The IMO says it is looking at those rules, along with collision regulations and others to see how they can work with autonomous shipping.

Matthews also points out issues with seafarer training and bunkering.

“What happens to the people who aren’t crewing the ships in the future?” he says.

And the ships would have to run on higher quality fuel, as crew members currently have to heat the fuel before use. That could drive up the fuel bill, Matthews adds.

“It’s not just a case of making this into a robotic ship,” he says.

A cost-benefit proposition

Being fully electric, the Yara Birkeland avoids the fuelling issue. And as the first ship of its kind, it does not pose imminent, existential questions about the maritime labour market.

But Orvik insists the ship is not merely proof of concept.

“It’s not a prototype. This is a ship that’s constructed to carry 20,000 to 30,000 containers per year. That is the aim,” he says.

“It’s actually going to do something. It’s not only for pilot purposes, or only for demonstration.”

While he is bullish on the future of autonomous ships, he does not foresee a world without engineers, deckhands and captains.

The trades in which autonomous shipping makes sense will have autonomous ships, Orvik says, the ones that do not will continue with crew onboard.

“Of course with technology it might improve operations,” he says. “If it does not improve operations, it will remain manned. I think it’s as simple as that.”

This story is part of the Shipping's Digital Future business focus. Read more in our next weekly edition.