What to do if you have a struggling shipbuilder? Get Chinese state money under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Having rejected a $1bn-plus bailout proposal for Uljanik Group, the Croatian state is so keen to get China Shipbuilding Industry Corp (CSIC) to play white knight that it has started to trumpet its interest in the BRI.

On the Chinese side, the state-owned conglomerate has agreed to send a delegation to Croatia to develop ways of cooperation in vessel design and construction.

The planned talks come after chairman Hu Wenming visited Uljanik's yards and met with the Croatian Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic and senior government officials in late April.

BRI's first shipyard

It looks as if Uljanik could turn out to be China’s first overseas BRI shipbuilding project. However, in the long run, it might be best for Croatia if the Chinese investor stays out of this one.

Beijing's state media and public relations officials elsewhere commonly pitch the BRI as a human development project to emerging economies, but in practice it often involves Chinese state lenders funding overseas infrastructure projects where their feasibility has been questioned by the private sector.

In the worst scenarios, the receiving countries are forced to cough up state assets on long-term concessions after falling into what critics describe as a “debt trap”.

The tendency of Chinese investors to get Chinese state players in for everything construction-related has also often drawn public backlashes overseas.

Bad omens

Strictly speaking, Uljanik is not an infrastructure project per se. But the shipbuilder, 25% owned by the state, has similar characteristics that appear omens of a failing BRI project.

One can hardly fault Croatian politicians for trying to rescue the group, which employs thousands of workers, most of whom have gone on strike due to unpaid wages.

Founded as a shipyard for the Austro-Hungarian Navy in 1856, Uljanik has focused on building MR-sized tankers, car carriers and ro-ros in recent years, while seeking to enter the cruiseship sector.

Despite the industry-wide shipbuilding overcapacity, Uljanik has been a financial blackhole for way too long.

Citing official figures, the Economist Intelligence Unit says that Uljanik’s Pula facility and its Rijeka-based subsidiary 3 Maj received $2bn in state subsidies between 1992 and 2017.

Still the yards are expected to go under within weeks if no investors are willing to absorb their debts.

For BRI projects that do not make much business sense, China tends to take a hard stance in extracting value — either in commercial or political forms

It is estimated the Croatian government would need to spend more than €800m ($897m) to resolve the crisis — something it is unwilling to do.

Since Beijing is keen to establish more footholds in Europe for the BRI, it makes sense for Croatian politicians to get CSIC onboard as a temporary solution — the next general election will be held before 2021.

Commercial perspective

From a purely commercial perspective, CSIC would not benefit much from taking over the yards within Uljanik, however.

As one of China’s two largest shipbuilding groups, CSIC has abundant capacity in constructing the type of vessels built by Uljanik.

While it wants to gain expertise in cruiseships to exploit growing demand in the Chinese market, Uljanik itself is also a newbie in this sector.

Moreover, CSIC will gain little by selling merchant vessels from the Croatian yard instead of China, as Brussels does not incentivise European owners to order from European yards.

And it is highly unlikely that CSIC will relocate any naval shipbuilding operations to the West.

Business development aside, CSIC does not appear to be in robust operational health for such a takeover.

The company does not issue results regularly, but the financial reports of its Shanghai-listed unit China Shipbuilding Industry Co (CSICL) — which controls some of CSIC’s best assets — provides some clues.

Net results of CSICL in 2018 were 51% below Bloomberg consensus, while its operating losses widened to CNY 626m ($91m) in the first quarter of 2019 from CNY 270m in the same period of last year.

With declining orders for merchant ships, JP Morgan expects the company’s return on equity to be below 2% in 2019-2021.

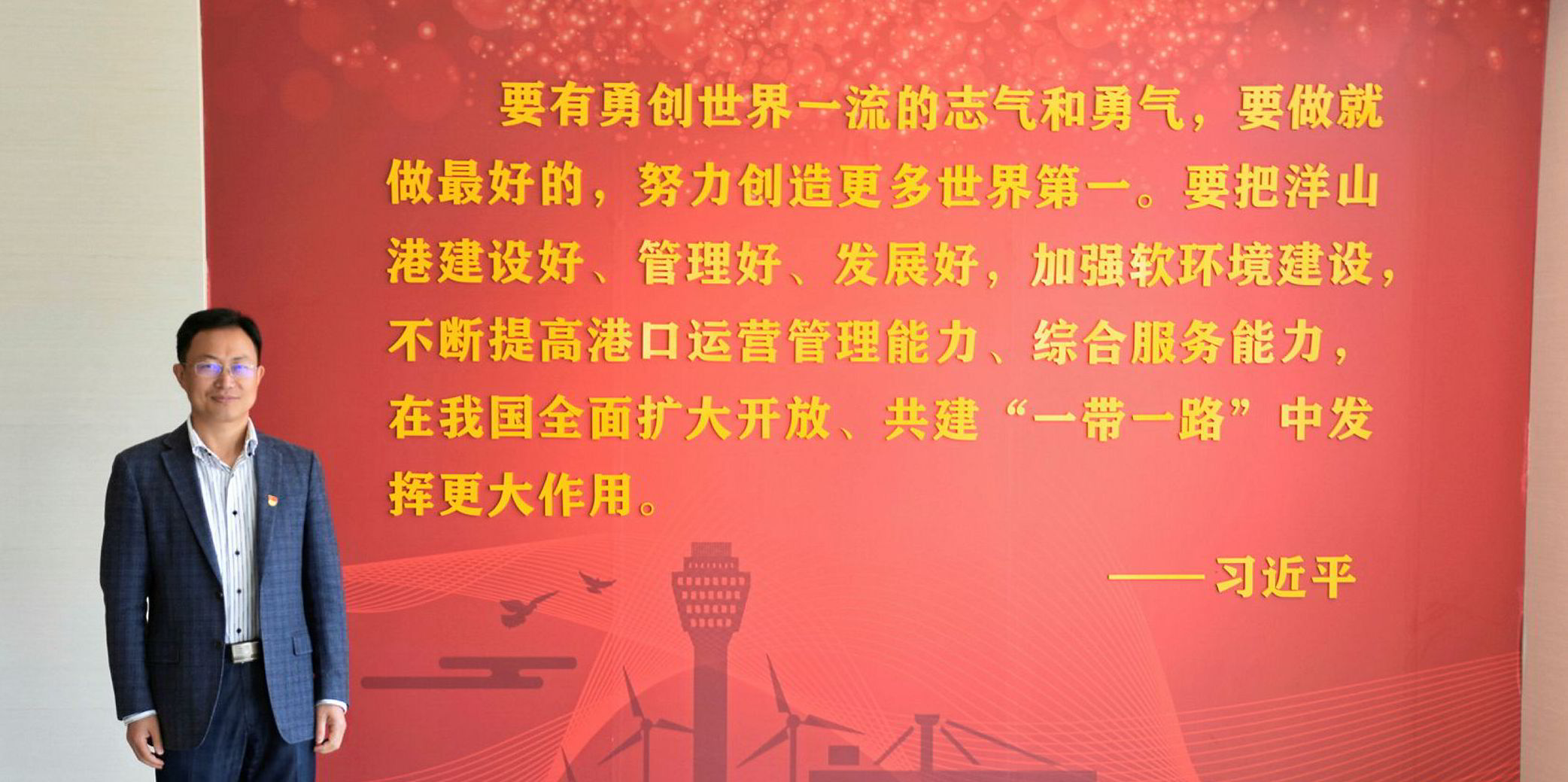

'Croatia an integral BRI hub'

This is perhaps why CSIC describes Croatia as an “integral hub for the BRI” when mentioning the shipbuilding cooperation on its website.

Labelling an investment in Uljanik as a BRI project would grant CSIC better access to state funding, a leeway necessary for meeting the tricky dual goals of maintaining business sustainability and fulfilling Beijing’s strategic ambition.

Yet all can go haywire at a later stage.

For BRI projects that do not make much business sense, China tends to take a hard stance in extracting value — either in commercial or political forms.

Eventually, Croatia may be paying more than what it would need to spend on managing the short-term economic pains if Uljanik simply declares bankruptcy.