Ten years ago, Maersk Tankers did one of shipping’s first green retrofits on one of its VLCCs.

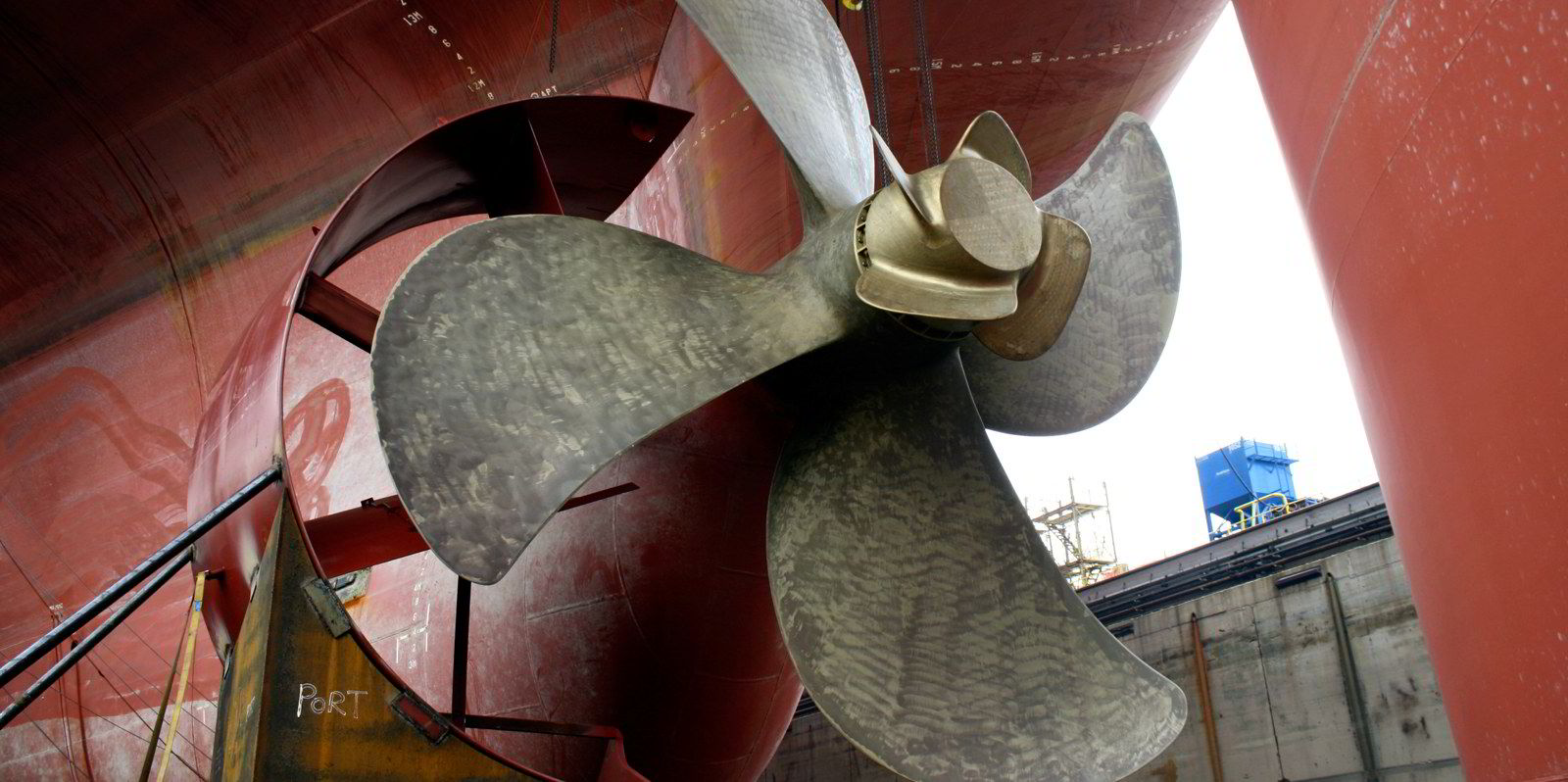

The 318,400-dwt Maersk Ingrid (built 2012) was fitted with a Becker Mewis Duct, a propeller boss cap fin and just about every energy-saving device available on the market at the time.

The aim of the trial — funded in part by the Maritime & Port Authority of Singapore’s Green Technology Fund — was to generate fuel savings of between 7% and 8%.

Fast-forward a decade, and Maersk Tankers spin-off Njord is back in Singapore with the opening of its first office in Asia.

Decarbonisation was not high on shipping’s agenda when the Maersk Ingrid was given its green retrofit. But, with oil trading at close to $140 per barrel, shipowners were looking at reducing fuel consumption.

The Maersk Ingrid was being put through a green retrofit even though nobody called it that at the time.

Today, with International Maritime Organization emissions deadlines for 2030 and 2050 set in stone, the decarbonisation race is full on.

Njord, a green technology service formed in January 2022 as a partnership between Maersk Tankers, Cargill and Mitsui, brings shipowners, charterers and financiers together to accelerate cost-effective emissions reductions on existing ships by developing tailor-made packages of technologies that are combined to maximise energy and emissions savings.

Older vessels are not Njord’s only target. It also designs packages for conventionally fuelled newbuildings.

The company helps clients screen their vessels to determine the potential of what they can do by combining the many different technologies out there today. It then helps them design that solution and monitor the performance.

“The technology has come a long way since the Maersk Ingrid project. We have a portfolio of more than 30 different technologies and solutions now,” Njord managing director Frederik Pind told TradeWinds on the sidelines of Marine Money Week Asia in Singapore.

“But we still use that as a key flagship project. That testing is what has helped us define how to combine a multitude of technologies.

“Contrary to many expectations, the two [original 2013] technologies complemented rather than counteracted each other. Altogether, we deployed seven technologies, resulting in savings of just under 10%.”

Pind said fuel savings of between 7% and 16% can be achieved, depending on the package. In more than 180 retrofit projects Njord has worked on, fuel savings have averaged around 12%.

“We have been above 25%, but that’s when you start looking at wind-assisted propulsion, air lubrication and shaft generators in combination with some of the more basic stuff,” he said. “Here we’re talking 10, 12, maybe 15 technologies, and some of the more novel stuff.”

Pind said putting so much bling on a ship could easily cost upward of $10m, but the investment required for the more normal types of retrofits averages out at around $1m for a standard MR tanker. The total retrofit cost varies, depending on the expectations of the shipowner or charterer paying the bill.

“We always look at what is sensible for the vessel based on its current fuel profile,” Pind said. “We look at its operational pattern, for instance, which is quite crucial. For instance, if the vessel doesn’t trade in areas where it’s wind favourable, we wouldn’t look at putting wind on it because that doesn’t make sense.

“Some owners come to us and say they will trade the vessel for the next five years or until its next special survey, and then sell it. So they only look at technologies that have a return on investment within those five years. Charterers might have the vessel on time charter for the next three years, so they want an even shorter return on investment.”

Njord’s first expansion outside of its Copenhagen headquarters was in February when it opened a satellite office in Athens. Panayotis Bachtis, who previously worked for Danish vessel optimisation platform ZeroNorth, was hired to charge.

Given the size of the Greek fleet, which forms such a large proportion of the global fleet, Njord deems it key to decarbonising the industry.

“We see a great willingness on the part of Greek shipowners to invest in energy-saving technologies, with most owners already harnessing technology to cut emissions,” Pind said.

He sees huge potential for the Singapore office, headed by ship management and technology veteran Kaushik Seal. The strategic location will allow Njord to stay close to shipowners and charterers based in Asia.

“Demand is quite high in the region,” he said. “Out of the 60-plus owners that we’ve worked with so far, a quarter are based in Asia.”

Pind believes Asia offers unique opportunities. While describing Singapore’s adoption of new green technologies as quite advanced, he said in other South East Asian countries — Indonesia, for example — the process has not really started. “This makes it interesting, because here we start from scratch.”

Japan is another potentially lucrative market because its shipowners usually acquire tonnage against 10-year charters.

“In Japan, we can act as a neutral intermediary between a charter and an owner on what is the right thing to do,” he said. “We can try to facilitate the discussion or negotiation on who is willing to pay for what, providing the confidence that these technologies will actually deliver the results.

“Instead of it being a discussion between an owner and charterer, it is a third-party neutral opinion based on the experience. That has proven quite effective so far.”

With satellite offices in Athens and Singapore up and running, Pind is keen for Njord to have an even broader global presence.

“We haven’t really gone into the Americas yet,” he said. “That could be an option.”