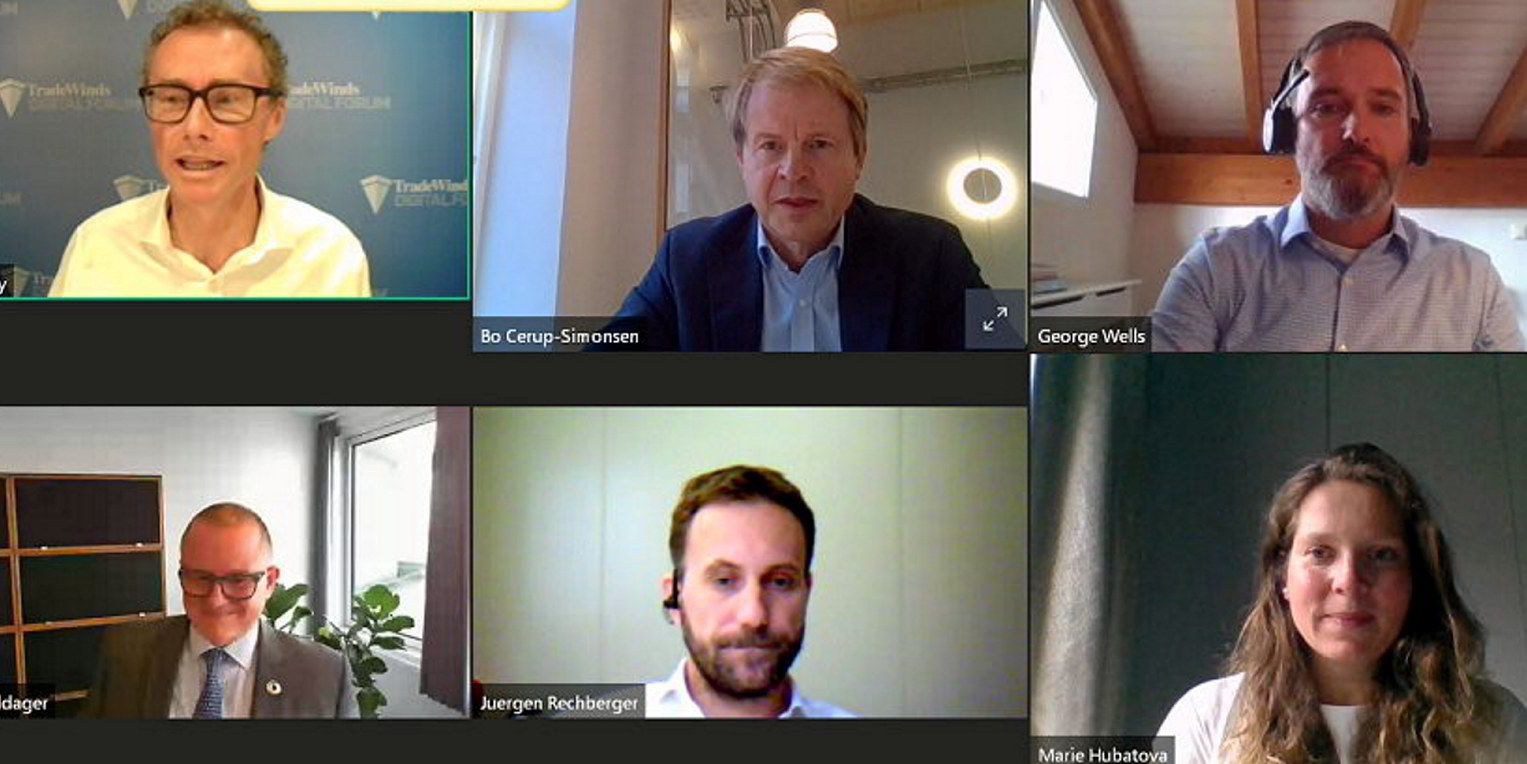

A panel of experts assembled by TradeWinds has given its verdict on how shipping will look by 2030 — and which future and transitional fuels are worth backing.

The Fuel of the Future digital forum picked over the merits of LNG, hydrogen, ammonia and sail propulsion.

But backing a clear favourite to power the fleet over the next decades is not easy — and Bjarne Foldager, head of two-stroke business at MAN Energy Solutions, is not going to try.

"We can't select one particular winner and we're not trying to pick a winner," he said.

Transition is well underway

Pointing to the use of methane, ethane and LPG as alternative fuels, he said: "For large merchant ships, the transition has already started. More than 240 ships are operating with some kind of dual-fuel engines."

Foldager expects ammonia engines to be in use by 2024.

He is convinced shipowners are making changes because "this is the only viable business that they see for the long-term future."

Foldager argued that the value of transitional fuels should not be underestimated on the road to the zero-carbon goal.

Future-proof?

"That is the way a shipowner can make his investment future-proof. Many shipowners, they get the question from their board, 'If we have to invest $100m in a big oceangoing ship, how can we guarantee our banks that this will not end up a stranded asset in five or 10 years?'

"That's why these transition fuels are so important,"

One big part of the transition is the use of LNG.

George Wells, global head of assets and structuring at Cargill Ocean Transportation, told the webinar that the trader and charterer had looked at LNG for a long time.

"We've struggled to get the economics to work for our tramp business," he said.

Wells put this down to the additional capex involved: "The payback was too long, it didn't work for us; we need a better LNG fuel infrastructure."

He argued that LNG can make sense for shuttle runs, where LNG is available to bunker, but Cargill has concerns over greenhouse gas savings on a well-to-wake basis.

"Savings are not as significant as some people are saying," he said.

Beware LNG as a fuel

Marie Hubatova, manager of international climate at the Environmental Defense Fund, said: "I don't think LNG is a good transitional fuel."

She pointed to a 2020 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation claiming that the gas can in some cases produce more emissions than heavy fuel oil over a 20-year period. This means an owner could have to make another investment in 10 years if a dual-fuel ship does not perform as expected.

And Hubatova said: "Building new infrastructure is not wise."

Cargill has focused on sail power, working with BAR Technologies, a spin-off from Olympic sailing champion Ben Ainslie’s attempts to win the America’s Cup.

Wells said trials have shown a 30% CO2 emission reduction for MR tankers on typical routes.

"I see no problem of prolonging the life of vessels if you're achieving those sorts of efficiencies," he said.

Wind power 'exciting'

Hubatova described wind power as "one of the great options you can implement on our existing fleet. You can make massive cost savings ... It's a step in the right direction, it's very exciting".

Jurgen Rechberger, head of hydrogen, fuel cells and Power-to-X at Norwegian technology company Teco 2030, is working to make hydrogen fuel cells a reality.

"I don't see a lot of hurdles. The technology is there. We need scale to bring down the costs. Logistics and hydrogen storage is the difficult part," he said.

Rechberger struggles to foresee a ship heading from China to Europe fuelled only by hydrogen.

“Liquid hydrogen storage is not going to be cheap,” he said, adding that ammonia is another option.

Bo Cerup-Simonsen, chief executive of Denmark's Maersk Mc-Kinney Moller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping, thinks the industry needs to move away from marginal changes.

Two factors

“We need to understand the new fuels we are aiming at,” he said. “It’s very difficult to pick a winner, but we need a good grip on it in a way that we avoid these stranded assets.”

Foldager added: "It always boils down to two basic factors: price and availability."

Rechberger believes there will be a fleet of hydrogen vessels on inland waterways and oceans by 2030.

And Wells said: "I'm sure we'll be operating zero-carbon vessels in the next 10 years."

For certain routes, zero-carbon fuels may be available in less than five years, he added.

"The problem is commercialisation," he concluded.