Bulker markets are braced for a slowdown from next year — literally. Much of the trading fleet will need to sail at reduced speeds to maintain compliance with shipping’s incoming emission regulations.

The International Maritime Organization’s Efficiency Existing Ship Index will enter into force on 1 January, measuring and restricting CO2 emissions, taking just the ship’s design parameters into consideration.

Bulkers will be required to reduce their carbon emissions by 15% to 20%, depending on their size, from their current Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) notation.

To comply with EEXI, it is thought that many bulkers will use engine power limitation, which will lower their maximum speed.

An analysis submitted to the IMO estimates that 40% of the bulker fleet would need to limit engine power to less than 80% of maximum power to be compliant. This estimate, however, is at the high end and is based on a simplified EEXI calculation that does not consider, for example, correction factors.

Older vessels built before the introduction of EEDI in 2013 will need more power limitation, according to analysis by classification society DNV. About 62% of the global fleet of live and launched bulkers was built in 2013 or earlier, according to fleet databases.

Reducing speed by 3% decreases a vessel’s fuel consumption by 10%, so slow steaming is considered an efficient way to save bunkers and therefore emissions.

It has the benefit of longer voyage times, which means more tonnage is taken out of the market, making vessel supply tighter in relation to demand.

But slow steaming carries safety risks, because slower vessels have less propulsive power and are therefore less manoeuvrable, especially in bad weather. That is particularly true for bulkers and tankers.

There remains a possibility that the new regulations could create “tiered” and more complex charter and S&P markets, pitting the vessels that are forced to slow down against those that are not. In a high spot market, being able to sail at your full service speed can be a distinct competitive advantage.

In reality, the impacts of engine power limitation will probably be less dramatic than they appear on paper. A bulker may need to limit its maximum power to 80%, for instance, but its operations will not necessarily be affected, because vessels usually run at a lower speed than their maximum.

In DNV’s analysis, the average engine load is estimated to go from about 60% to 55%. That is manageable. Some bulker operators to whom TW+ spoke say their modern or relatively modern fleets will not need to change much about the way their ships operate from 2023, if at all.

However, applying engine power limitation on a vessel will affect operational planning and flexibility, because the sea margin is reduced, making it difficult to catch up on delays and weather-related detours, for example.

Clarksons Research thinks incoming regulations such as EEXI, CII and the European Union Emissions Trading System will put pressure on older tonnage from 2023.

Bulker scrapping is expected to pick up next year, following a “normalisation” of markets from last year’s highs, according to Clarksons’ dry markets outlook report in September. “Around 25m dwt of scrapping is currently projected for next year, though significant uncertainty remains and market trends will also be a key driver,” it said.

Just 3.4m dwt of bulker tonnage is expected to be scrapped this year, the lowest level in years, according to Clarksons. But demolition activity is expected to increase by 640% next year to 25.2m dwt.

Low ordering activity in recent years also means the global bulker fleet is getting older. It is currently around 11.5 years old on average, compared with 10.2 years at the end of 2019.

This is meaningful in relation to the Carbon Intensity Indicator, which starts being monitored next year to address the actual emissions from shipping operations. CII rating thresholds will become increasingly stringent towards 2030, but levels have not yet been set beyond 2026.

Clarksons estimated in July that under CII, 40% of today’s tanker, bulker and container fleets will be rated D or E — the lowest rankings — if they are still trading in 2026 and have not modified their speed or specification.

There has been hope in the market that rules such as EEXI will help support bulker demand relative to vessel supply as the trading fleet reduces its speed.

But analysis by Maritime Strategies International (MSI) suggests that any supportive effects will be offset by the unwinding of port congestion, which will release ships back into the market.

More worrying still is the potent cocktail of factors that are making bulker markets even more volatile and unpredictable. MSI thinks dry cargo markets will come under “intense pressure” in 2023.

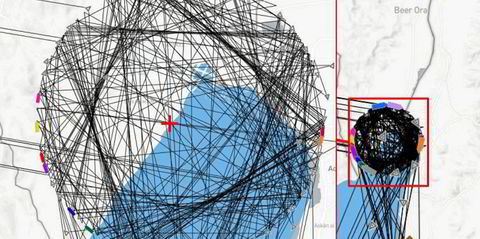

Data from VesselsValue shows the global fleet of dry cargo vessels averaged a laden speed of 11.11 knots and 11.71 knots in ballast during September. By October, it appeared to be speeding up again as the spot market came back to life.

Last November, the fleet hit average speeds not seen in more than 10 years. Average laden trips were 11.65 knots and ballast voyages clocked in at 12.18 knots, according to VesselsValue.

“One thing is clear from MSI’s analysis, though: the potential for a collapse in the freight market has been rising on the back of weakening economic activity across the world, lockdowns in China and an easing in port congestion,” the firm said in its dry bulk outlook report for September.

“MSI’s near-term forecast assumes a near-term upward correction in earnings followed by weaker markets next year; [asset] values, on the other hand, are projected to soften more gradually from Q2’s peaks.”

There is also a risk that increased scrapping could stimulate newbuilding activity. The bulker orderbook is at historic lows, which will surely not detract from the temptation to order new vessels.

Will there be any net benefits in terms of emissions savings, if owners are pushed into replacing those bulkers they have had to scrap? Building ships comes with a big environmental price tag, particularly when high-emitting steel production is taken into account alongside the transport of raw materials.

There is a short runway to meet the IMO’s targets — just eight years to reduce carbon intensity by 20% from the 2008 baseline — and a lack of visibility remains as to how the impacts of the incoming regulations will shake out.

For one thing, markets will be shaped to a degree by the attitude of regulators towards enforcement of these regulations and how this will be done in practice.

Observers have voiced concerns that this could cause vessels to become untradable if shipping adopts a hardline attitude of vessels being either “compliant” or “non-compliant” with emissions requirements set by charterers and regulators.

On the other hand, shipping has proved time and time again that it is good at finding ways to make things work.

But as all this work goes on and the industry becomes more committed and ambitious in its quest to reduce emissions, oil prices (ironically) remain the soft power in driving the green transition.

A high oil price will naturally incentivise owners to make their vessels more efficient and reduce consumption of expensive bunkers, including by slow steaming. Low bunker prices would delay progress.

The Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index applies technical standards to cut carbon dioxide emissions by ships from 1 January 2023 based on the Energy Efficiency Design Index adopted by the IMO for newbuildings in 2020.

The Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) will regulate existing ships above 5,000 gt from an operational perspective. It is worked out by taking a ship’s annual emissions from fuel used and dividing that by its capacity (deadweight or gross tonnage), multiplied by annual distance travelled in nautical miles.

The CII will be implemented via a new Part III of the Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) containing targets and an implementation plan that details measures to be applied.

From 2024, CII ratings will be assigned for the previous year ranging from the highest A to lowest C pass grades, while D and E results may be considered non-compliant.

Operators of ships rated D for three consecutive years or E for a single year will have to develop an approved plan of corrective actions to bring a vessel into compliance by the end of the next year.

The CII is based on 5% reduction in carbon intensity in 2023 relative to a 2019 base level. Its requirements will get stricter by 2% per year until 2026. The IMO has yet to decide on further levels.