Shipowners are constantly fending off cyber-threats from Russia.

“Through our service operations centre, we identify cyber-attack attempts from Russia on a daily basis, same as we do from other countries. So far, none of these attempts have been successful,” one owner tells TW+.

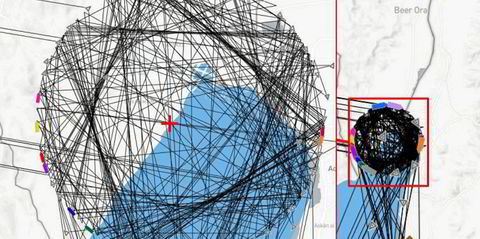

The maritime sector suffered at least 1,000 “operational technology” attacks from the beginning of 2017 to the end of 2020, according to Israeli cyber security firm NavalDome.

The owner, which would only speak anonymously to prevent alarming clients by attaching its name to cyber-threats, protects itself from the constant onslaught by restricting Russia’s access through firewalls that use a geolocation feature.

“Given that offices and vessels are interconnected, any compromised site could easily spill over to the other side as well,” the company adds. “Leakage of personal data is also a concern.”

Shipbrokers are also on the lookout for attacks, especially since container lines have faced cyber threats before suspending business with Russia.

“It doesn’t seem a stretch to think that Putin might target them as punishment, or just to cause more disruption to the rest of the world that opposes him,” a broker tells TW+.

“With any luck, he is too preoccupied with a war that appears to be slipping from his control to bother.”

But despite the most advanced protections and strenuous vigilance, it is impossible to know for sure what threats may be on the way and how to defend against them.

“Nobody really knows what the Russians are planning,” says Robert Dorey, chief executive of UK maritime cyber security firm Astaara Group.

“This is obviously an area where risk is increased and therefore all the members of the maritime community need to take this opportunity to reduce their vulnerability.”

He points out that previous high-profile attacks such as the 2017 NotPetya attack targeted many other sectors besides shipping: “Nobody was targeted specifically because they were a shipping company or a maker of chocolates, or anything else, for that matter.”

It is hard to know to what degree Russian hackers are targeting maritime, but companies with old software are certainly more vulnerable, Astaara chief cyber officer William Egerton warns.

“Whilst we don’t know what they’re planning, the Russians are planning something,” he says. “I think the prudent response has got to be to do something to reduce your attack surface and make yourself as less vulnerable as you can without necessarily throwing out the baby, not communicating with everything. Life has to go on.”

Egerton says companies near the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, in a Russian port or north of Finland are at particular risk, but any maritime entity must keep its guard up.

The unattributable owner says it keeps its IT systems updated and uses a virtual private network with two-factor authentication to reach its servers.

“Every year, we carry out cyber security simulation attacks to assess the robustness of our systems and controls,” it says. “We also have a rigorous backup process in place to allow rapid recovery in case of a cyber-attack.”

It has carried out a “rigorous” cyber security programme over the past two years that includes deploying advanced end-point protection and upgrading firewalls.

Astaara Group says the best defence against cyber-attacks includes:

- identifying and understanding critical systems and protecting them foremost

- training employees at all levels on minimising risk

- encouraging and facilitating sound cyber practices

- managing access carefully with two-factor authentication

- conducting cyber-attack drills to prepare for actual incidents

- investing wisely and adequately in cyber security

- backing up systems and developing recovery plans

It also formed a 24/7 monitoring and incident response team, training onshore and at-sea personnel and developing cyber security manuals with relevant guidelines.

Dorey says not many clients consider themselves highly vulnerable to attacks, but those that do fear levels of attack that are simply beyond hackers’ capabilities.

The company, which has grown to 11 employees and about 50 clients worldwide since Dorey, a former underwriter, founded it in 2019, says there has been an increase in enquiries from its key markets, mainly about testing whether firms are operating at the International Maritime Organization 2021 levels of cyber maturity.

“A lot of shipowners are encouraged to think by a lot of people in the cyber security world that their ships are vulnerable to being hijacked, or that the operational technology can be compromised in such a way that they lose control over their assets,” he says.

“The real risk is just the compromise of systems which delay or degrade the operational resilience of somebody’s ship.”

The strongest defence against such attacks is segmenting IT systems and implementing best employee practices through rigorous training, according to Egerton.

“Hackers rely on people either being lazy or behind the curve, and if you got your eyes on and you’re taking care, then it’s more difficult to hack you because it’ll be noticed quicker,” he says.

“But if you think it’s just an IT problem and throw it to the guy with a piece of kit to implement, he’s not gonna save you.”

It is hard to say how many state-implemented or state-sponsored cyber-attacks happen, because many companies do not report them out of embarrassment.

“The companies that aren’t as mature will hide the fact they had a cyber incident because they couldn’t manage it right,” Egerton adds.

The IMO does not have any statistics on maritime cyber-attacks, but it issued a set of recommendations in 2017 on how to prevent them.

They include defining personnel roles and responsibilities for cyber risk management, developing means to detect attacks and threats, and installing backup systems to restore compromised capabilities as quickly as possible.