European buyers need alternatives to Russian pipeline gas and LNG supplies, and they want them fast.

Suddenly LNG, which barely gets a mention in energy strategies, has been shoved into the limelight as the import solution that can step in.

This story is part of a series in TW+ magazine on the wide-ranging impacts of the Russia-Ukraine conflict on shipping. Read the full stories when the magazine is published on 20 May.

But it is not that simple. Nor is unscrambling the market impact for the LNG carriers that will transport it.

Consultant Andy Flower estimates that for Europe to replace the 150bn cbm of Russian gas that it currently buys, it would need to import more than 110m tonnes per annum from an industry that is already supply-constrained for the next few years.

US President Joe Biden has promised to make an extra 15bn cbm of LNG — around 11m tonnes — available to Europe by the end of this year.

But as Flower points out, Biden did not say where this LNG would be sourced from, although it was widely assumed to be the US. And ultimately, the president has no say in who will buy it and at what price.

That said, the US is one of the few exporters that could divert some existing volumes. It is also the place where new projects are being developed and fast-tracked.

Europe was already in LNG buying mode at the turn of the year.

An extreme cold snap in Asia a year earlier had sent volumes east, and European storage was widely depleted. The move to ditch Russian gas and longer-term concerns over energy security have heightened this trend.

Flower says Europe imported 31.9m tonnes in the first quarter of 2022, about 66% more than the 19m tonnes in the same three months of 2021 and a huge rise on the 9m tonnes in the fourth quarter of 2021.

The US has been the main LNG supplier to Europe this year.

In the first quarter of 2022, Flower says 72% of US LNG exports were shipped to Europe, with 22% going to Asia and 6% to the Americas. Last year, 34% of US volumes went to Europe, 50% to Asia and 15% to the Americas.

It is still early days to see how this picture might unfold for LNG carriers.

Fearnleys’ advisor for LNG shipping & renewables, Ina Bjorkum Arneson, says more LNG is going to Europe.

In the short term, this will contribute to reduced tonne-miles and tonne-time, with LNG carriers covering shorter distances and fewer vessels waiting for Panama Canal transits, she says.

In the first quarter of 2022, Fearnleys’ data shows lower average sailing distances for LNG carriers over the same period a year earlier. But tonne-mile was higher, due to more traded LNG. Fleet utilisation was relatively high.

However, Arneson says this could be compensated for by higher volumes, from returning and new capacity.

| 2021 | |||

| Month | LNG discharged (mt) | Average distance (nm) | Tonne-mile (bn) |

| January | 32.5 | 4,355 | 142 |

| February | 32.5 | 4,417 | 144 |

| March | 33.3 | 3,895 | 130 |

| 2022 | |||

| Month | LNG discharged (mt) | Average distance (nm) | Tonne-mile (bn) |

| January | 38 | 4,209 | 160 |

| February | 33 | 4,019 | 133 |

| March | 36 | 4,015 | 145 |

Several liquefaction plant outages and production problems took LNG out of the market last year. But some of these issues are expected to be resolved this year. Shell’s Prelude floating LNG unit has restarted and Norway’s Snohvit LNG is due back online.

In addition, a wave of new projects, most of them in the US, are expected to be greenlighted this year amid concerns over energy security in Europe. It can give impetus to projects such as Tellurian’s Driftwood LNG and Sempra Infrastructure/TotalEnergies’ Cameron LNG expansion.

Flower says that before the Ukraine war, a further 48m tonnes per annum of LNG from four US projects was due to be sanctioned, supply that is scheduled to come onstream from 2025 into 2027.

But now he has pencilled in 30m tonnes more to be greenlighted, with fresh announcements continually emerging on projects.

However, this new supply will not come onstream until the second half of this decade.

Poten & Partners head of shipping analytics Jefferson Clarke says analysing the immediate LNG shipping impact of the Ukraine crisis is a two-step process.

He says the forward price curve indicates that average voyage distance will continue to decrease for the next 12 months as US exports shift from Asia towards Europe.

“All else being equal, shipping demand would fall. However, all else is not equal here,” he adds.

“Charterers are reluctant to sublet vessels into the spot market, because of logistical issues or an extremely high opportunity cost, so utilisation — measured as the percentage of time that vessels are laden — is falling too.”

The second step is to estimate the impact of lower utilisation on shipping demand.

Clarke says a slight reduction can have an outsized impact. In 2021, utilisation was estimated at 44%, but preliminary data over the past two months indicates it dropping to 41%.

“This slight decline is enough to offset the decrease in tonne-miles, so the net effect is shipping demand remains flat or even slightly increases.”

Poten global head of business intelligence Jason Feer adds another issue: Asian gas inventories are also low.

He says these buyers have been staying on the sidelines for the past few months hoping that prices would ease with a resolution to the Ukraine crisis.

“They cannot do this for much longer and we have heard that a number of major buyers are preparing to hold buy tenders and to make spot purchases,” Feer adds.

“This could push overall prices higher and flip the arb [arbitrage] to Asia, so that could lead to a tightening of the freight market as more volume flows east.

“If the arb opens again, then the real question for shipping demand is if utilisation can rise again in line with average voyage distance. If not, the shipping market will only get tighter.”

One owner points out that long-term trade changes are likely for LNG and other shipping sectors: “I think something fundamental has changed. I don’t see Russia becoming a trusted business counterparty after what has happened.”

The owner says large corporations will be “extremely reluctant” to go back to Russia, even if the war ends, and it will take time before sanctions are lifted. It will be a long, slow process to rebuild the necessary trust for business deals.

The owner and other LNG players highlight an emerging divide between owners.

Some LNG shipowners continue to lift Russian cargoes, such as those with vessels locked into long-term time charter contracts with Novatek-controlled Yamal Trade, which works out of Singapore.

But some players say that as sanctions ramp up, these owners could be in danger of breaching contracts with other counterparties due to their Russian business involvement.

“It’s going to be a complicated situation for a lot of companies,” one industry observer tells TW+.

Overall, however, shipowners appear largely positive as the market refocuses. “There is certainly a bright future for LNG shipping,” one consultant says.

But many shy away from seeming to see opportunity in what they stress are “tragic circumstances” and “a humanitarian crisis”.

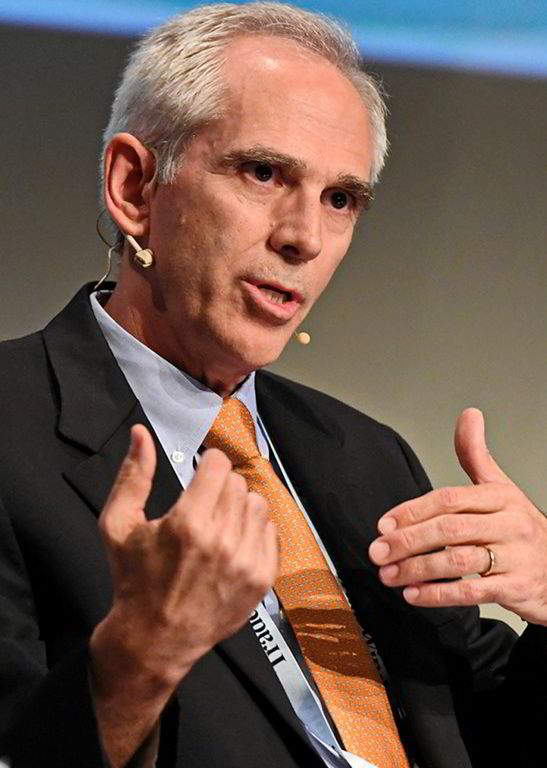

Former Maran Gas Maritime executive vice president Richard Gilmore, who recently relocated to the US and is working on as a consultant for the company after a career in the industry, believes the market shifts will balance out for LNG shipping.

Giving his own views, Gilmore says that while the shorter tonne-miles will be an immediate issue, greater volumes will be needed to replace Russian gas and “take up the slack”.

More broadly, he sees the crisis as having the potential to lead to a rethink on energy transition plans globally: “When there is no fuel, people will burn anything, and gas is still the best solution.”

While the experienced industry professional admits to being biased towards LNG, he says it has a strong role to play as a complement, not a competitor, to renewables in getting the world towards a zero-carbon future.

“I would hope that some of the governments and policy leaders would see the strength of the LNG industry in being flexible and able to respond, but also as the best short- to medium-term solution offering the least carbon of any fuels,” Gilmore says.