When it comes to renewing the United Nations-sponsored corridor out of Ukraine, grain is not the only thing that matters.

Recent statements by UN and Russian officials point to fertilisers as a key aspect hampering a second extension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI).

Speaking to journalists in Moscow on 9 March, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov said his country’s grain and fertilisers still face export obstacles, despite being formally excluded from Western sanctions.

“Sanctions prohibit Russian ships with grain and fertilisers from entering … ports, foreign ships to pick up these cargoes … [Russian bank] Rosselkhozbank JSC to use the Swift [interbank] system,” Lavrov told journalists on Thursday.

He said Ukrainian grain exports under the safe corridor scheme must go hand in hand with “removing all obstacles to export Russian grain and fertilisers”.

“The deal is a package deal. You can only renew what is already in progress. If the ‘package’ is half-fulfilled, then the issue of extension becomes complex,” Lavrov said.

In previous statements in February, another Russian foreign ministry official had protested at new Ukrainian sanctions on Russian transport and chemical factories, which included fertiliser makers, as well as calls by Kiyv for Western nations to adopt such measures as well

The West has so far been careful to exclude Russian fertilisers from its strict sanctions, given their importance for food security.

Self-sanctioning and indirect financial sanctions are nevertheless diverting or obstructing the trade, as TradeWinds reported in an analysis last month.

‘Don’t care if you love or hate Russia’

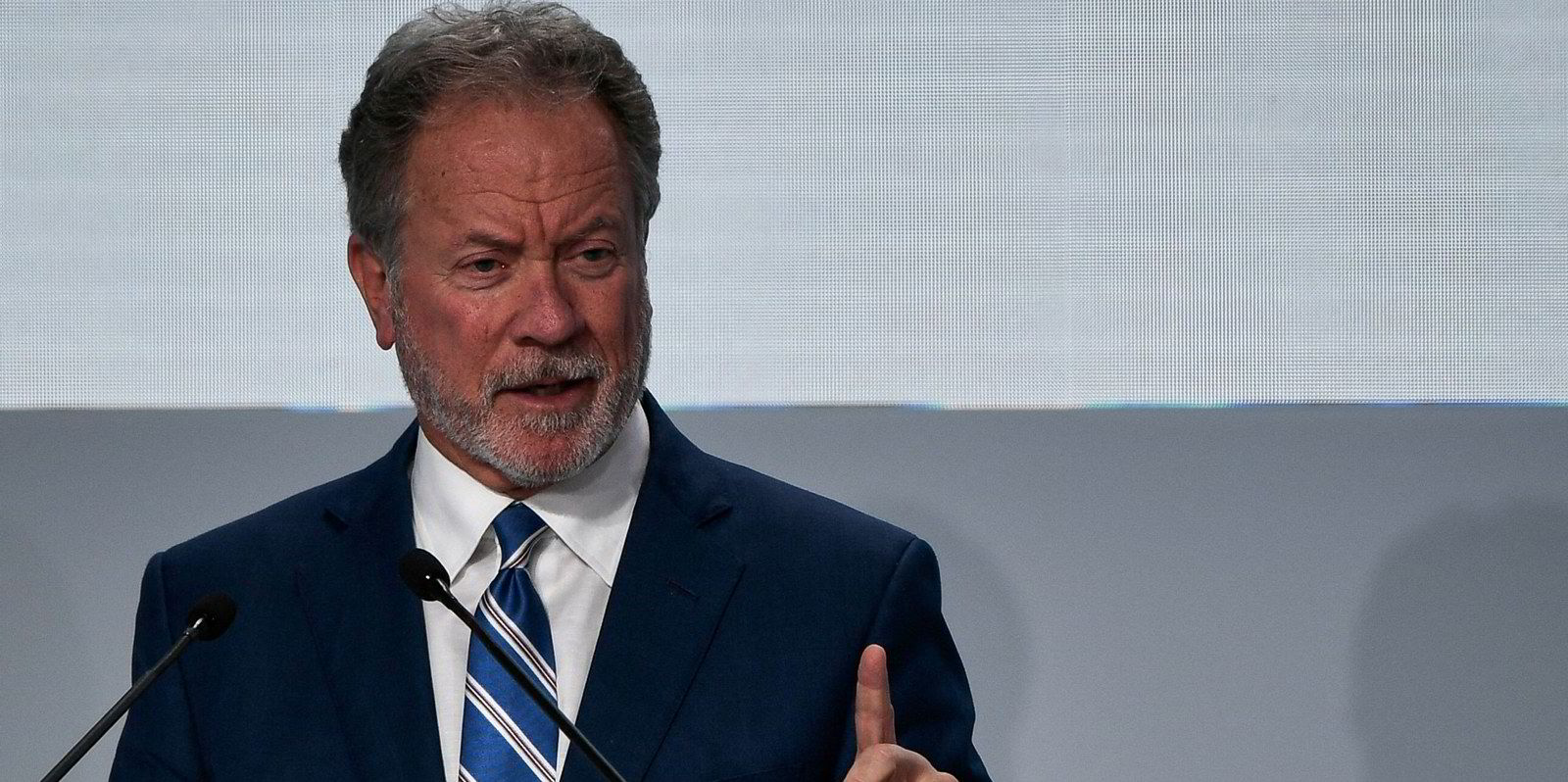

Russian fertilisers also featured largely in a dramatic appeal by a senior UN official this week to renew the deal.

Half the world’s food production and consumption depends on fertilisers, and with Russia being a major manufacturer, its exports are essential to maintain food security, said David Beasley, executive director of the UN World Food Programme (WFP).

“I don’t care if you love or hate Russia – you got to have fertiliser right now,” Beasley told the defence committee of the UK’s House of Commons on 6 March.

“That’s just the reality — if you want to have hell on earth, don’t take their fertiliser,” he added.

With Ukrainian fertiliser production in the doldrums and the outlook for Ukraine grain production in 2023 uncertain, it is more urgent than ever that ships continue to flow out of the country, to get at least the foodstuff stored from previous harvests out, Beasley said.

“It is extremely important those silos get empty, those ships get loaded and politics be thrown out of the window so that we can move these ships,” he said.

The WFP has chartered at least 16 vessels under the BSGI to carry Ukrainian grain to countries in the Middle East and Africa.

With food production tight across the world, the BSGI is essential to maintain food security in many areas, especially after the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria last month.

“We’re facing a humanitarian crisis unlike any we’ve seen since World War II,” Beasley told the British Members of Parliament.

“If we don’t address this BSGI strategically … we’ll have another wave of Syrian refugees hitting into Europe in the next 12 months. It is that serious.”

To help renew the deal, which has facilitated the export of 23m tonnes of Ukrainian foodstuffs since 1 August, UN secretary general Antonio Guterres visited Kyiv on 8 March.

“I want to underscore the critical importance of the rollover of the BSGI on 18 March and of working to create the conditions to enable the greatest possible use of export infrastructures through the Black Sea,“ he said after talks with Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Guterres’ point addresses longstanding Ukraine demands to expand the scope of the scheme to cover more than the current three ports.

Another Ukrainian demand has been that Moscow stop choking the scheme by ordering its BSGI inspectors in Istanbul to drag their feet, causing a backlog of more than 140 ships in the Bosphorus.

Highlighting the fragility of the scheme, Russia briefly pulled out of it at the end of October, accusing Ukraine of having sent drones through the corridor to attack its warships.

(This article was updated after original publication to add comments by Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov)