Times are changing for Oldendorff Carriers and not just in the world in which the German shipowner operates.

After 103 years in business, the company has grown to be among the world’s biggest bulker operators.

But its low-key public profile belies its reputation as a heavy hitter in freight markets.

It is a company that originated some of the trading strategies now widely adopted by others.

The company was at the forefront of incorporating cargo trading into its vessel operating business, which has blossomed and boomed over the past 30 or so years.

Then there are more niche trades like transporting wind turbine elements for offshore installations, a business that over the past few years has seen an influx of new entrants, hoping to squeeze more value out of backhaul routes.

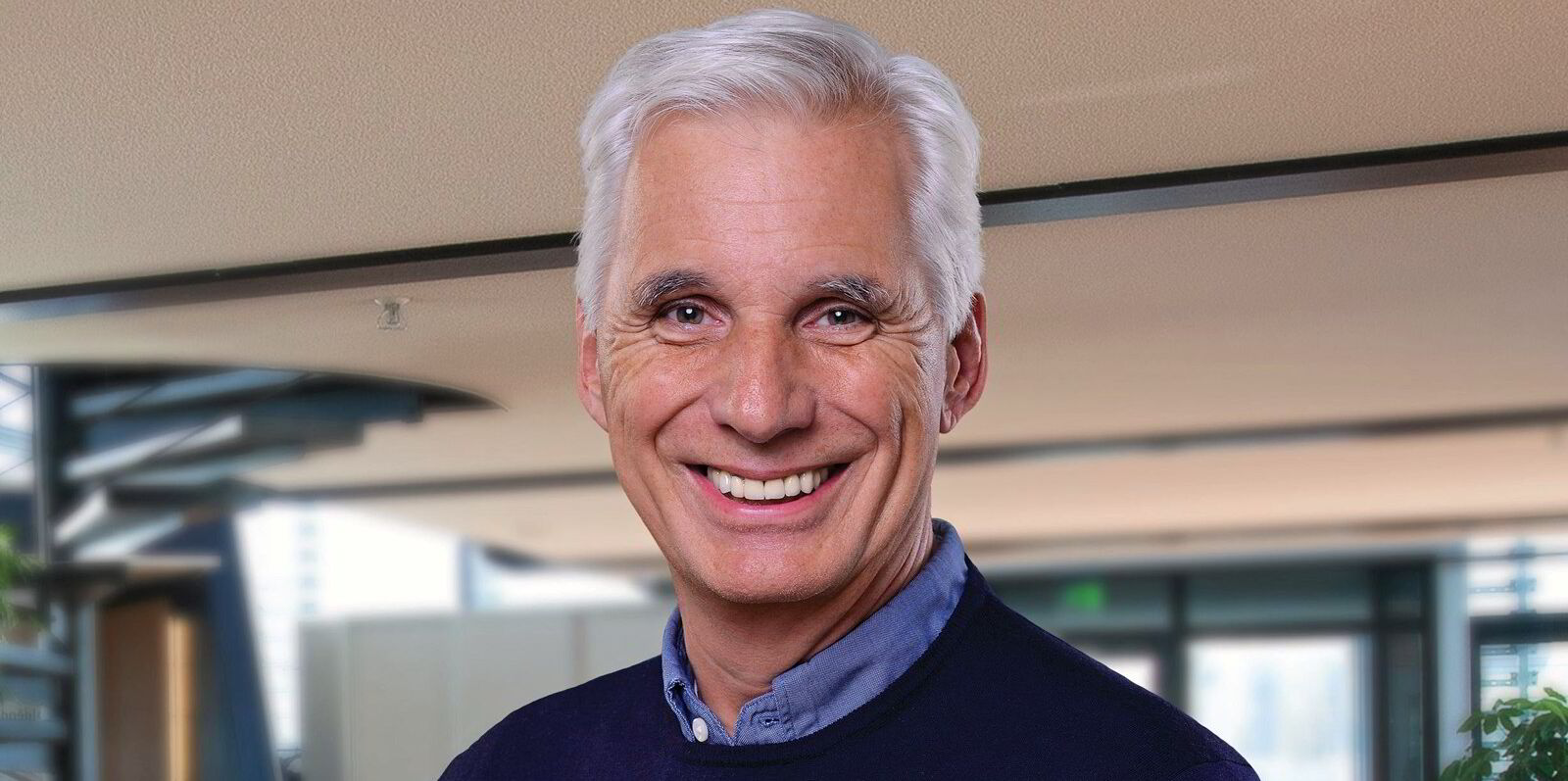

But Oldendorff was there first. It has been doing unitised wind turbine business for around 20 years, as chief executive Patrick Hutchins points out.

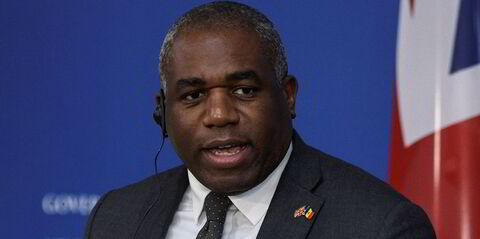

Hutchins is warm and laid-back but — much like the group’s chairman, Henning Oldendorff, — is intent on remaining low-key.

Both met with TradeWinds in Hamburg to give a rare glimpse inside the world of the German firm.

Hutchins is a 25-year company man who succeeded Peter Twiss in the role in April last year.

He started in Lubeck — Oldendorff’s historic base — doing handysizes and supramaxes in the Atlantic, after which he moved to Singapore to open a new office.

Between 2011 and 2013, he was seconded to Deutsche Bank, where he was part of the bank’s commodities and derivatives team, which he considers a particularly formative period in his career.

Then it was time to head to London, where he initiated Oldendorff’s baby capesize business. The owner-operator had six baby capesizes in 2013 and today has almost 40.

“I’ve done all the ship sizes and projects,” Hutchins notes with some pride.

Oldendorff is in something of a growth phase right now, backed by fresh energy and a lot of cash harvested during the boom markets of the past few years.

Oldendorff is said to have turned over billions in the pandemic years, but such claims cannot be seen on paper — its financial accounts are not published publicly.

But freight markets have since returned to reality and Oldendorff is adapting.

“We’re becoming more aggressive in our spot operations,” Hutchins said.

“We nailed it on capes and have done well on panamax and the smaller sizes, despite very challenging markets,” he said of this year.

Hutchins thinks Oldendorff can outcompete rivals in how it positions its fleet and also create efficiencies through its scale.

The fleet is fed by Oldendorff’s network of cargo offices worldwide.

There are strong hints that Oldendorff is beginning to think seriously about if and when to start buying ships again, having sold 20 bulkers this year.

“The values are too good to ignore,” Hutchins said. “We took some profit; we’re a value player at the end of the day.”

A key indicator for Oldendorff was that secondhand values were above newbuilding values. Meanwhile, the underlying earnings “made no sense”, Hutchins explained.

“No one ever goes bust by taking profit,” he said.

“We have the firepower to buy back — when the timing is right, we will reload and load more.”

This is something that Henning Oldendorff alluded to in his conversation with TradeWinds.

The Oldendorff family this year established its own family office for non-shipping investments, which will provide another way for the family to deploy capital.

Henning told TradeWinds: “A large portion will be liquid and available for reinvesting in our core shipping business at the opportune time.”

Oldendorff’s future as a family-owned business seems assured. In November, Henning’s three daughters took stakes in the company, although they will remain passive shareholders initially.

Henning has confirmed he is not going anywhere any time soon and will continue as chairman and key shareholder.

Oldendorff is, of course, known for its bulker operating business, which — at typically 650 to 700 vessels — is one of the world’s biggest. Its owned fleet comprises 105 bulkers and another 20 vessels involved in the transshipment business.

Hutchins wants to see the firm grow, without compromising quality, and maintain its presence. It is constantly looking for opportunities, he said.

Oldendorff set up a new Brazilian office in Sao Paulo last year, with the chief executive calling in a real growth area for the company.

He said its success to date is down to the fact it is staffed with the right people — namely locals who know the business inside out.

“We’ve got the right people and the right structure,” he said.

The Sao Paolo office handles panamax, supramax and handysize chartering, mainly for grain and parcelling trades.

Oldendorff previously had a Brazil office in Rio de Janeiro — set up by Hutchins — which was “extremely busy” for about five years until Brazilian steel exports died off.

The other key area for growth right now is Dubai. Oldendorff opened its first Middle East office in the emirate around 11 years ago.

Dubai is a key base for its transshipment operations and complements the company’s India cargo desk.

It handles classic Middle Eastern dry commodities like limestone for the cement industry, clinker and iron ore across supramaxes up to capesizes.

With its vast global network of vessels, personnel and cargo, Oldendorff generates a wealth of data. However, Hutchins believes there is still potential for the company to enhance how it utilises this market information.

Artificial intelligence will be key going forward. The owner is setting up an AI data centre and has begun working on some initial projects.

“AI has a future; we are constantly evaluating and using different types of AI to assist in improving efficiencies and helping us evaluate markets,” he explained.

“We can drill down on certain cargo flows and put in our own processes internally to identify opportunities.”

Hutchins said he wants to see his charterers focus on attention to detail, “quality fixtures” and better interaction between the company’s operations and chartering teams.

Looking ahead to 2025, Oldendorff is not so concerned about the outlook for capesizes. However, there is a cautious eye on the delivery schedule for panamaxes and supramaxes, which will add extra supply to the trading fleet.

A big question for next year will be the status of the conflict in Ukraine and relations with Russia, but it remains impossible to know what will come next.

“We can react to macro[economic] changes quickly at Oldendorff,” Hutchins said.

“We’re nimble and we can be reactive quickly, once we take a view on something.”

Oldendorff looks at its business over a three-year horizon for the market.

Hutchins thinks it is impossible to judge the market much further out than that, “but in the longer term, if the value is there, we’ll always consider it”.

Certain commercial teams have departed to work for rival operators over the past 12 months.

Staff exits have not had much effect on day-to-day business at Oldendorff, according to Hutchins.

“Change means opportunities for other people’s careers,” he said.

“We have a very open, flat management structure and a friendly environment of respect.

“It’s up to us to ensure that we have the right environment to keep people happy.”

Hutchins want the Oldendorff company name to stand for Integrity. “What we say goes. We’re very straightforward, both internally and externally,” he said.

“We have a great team across all departments. We want to create an environment where people are happy to work, where you pay people well and give them the freedom to act.”