After throttling even the little that was left of Ukraine’s waterborne grain exports, Russian President Vladimir Putin takes steps to supplant his enemy’s grain in international markets.

In an article he published on 24 July, the Russian leader said his country stands ready to fill the gap he himself has helped cause by invading Ukraine last year and by pulling the plug on the United Nations-led Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI) earlier this month.

“Our country is able to replace Ukrainian grain, both on a commercial basis and free of charge, especially since we again expect a record harvest this year,” Putin wrote in the text addressed to African leaders and policymakers he is hosting in St Petersburg on 27 and 28 July.

Bilateral grain deals are expected to be at the centre of the second Russia-Africa summit and are characteristic of Moscow’s wider ambitions.

“Despite the sanctions, Russia will continue to work energetically on organising the supply of grain, food, fertilisers and more to Africa,” Putin wrote.

Russia’s withdrawal from the BSGI on 17 July and subsequent threats issued by Moscow against commercial ships approaching Ukraine have likely spelt the end of the long-distance grain trade out of Ukraine’s big ports on the northern Black Sea coast.

Ukrainian pleas for alternative routes under UN, US or Turkish protection are falling on deaf ears, as none of these parties are willing to confront Russia militarily and risk World War III.

Asked by reporters on 17 July if the US were considering providing such guarantees, National Security Council spokesman Admiral John Kirby said: “You’re suggesting that we should just try to run a blockade … that’s not an option that’s being actively pursued.”

There’s no alternative, really

This in effect leaves a European Union-backed combination of rail, road and Danube barges as the only way to get grain exports out of Ukraine.

Shipping experts and other officials, however, recognise that this will in no way fully replace the quantities the country was able to export by sea.

Apart from the logistical difficulties of combined overland transport, the Danube has other shortcomings.

“One must always have in mind that the water level in the Danube is getting lower day by day due to drought, so it is not possible to load barges with wheat at full capacity, making the river a less attractive alternative,” analysts at Athens-based Xclusiv Shipbrokers wrote on 24 July.

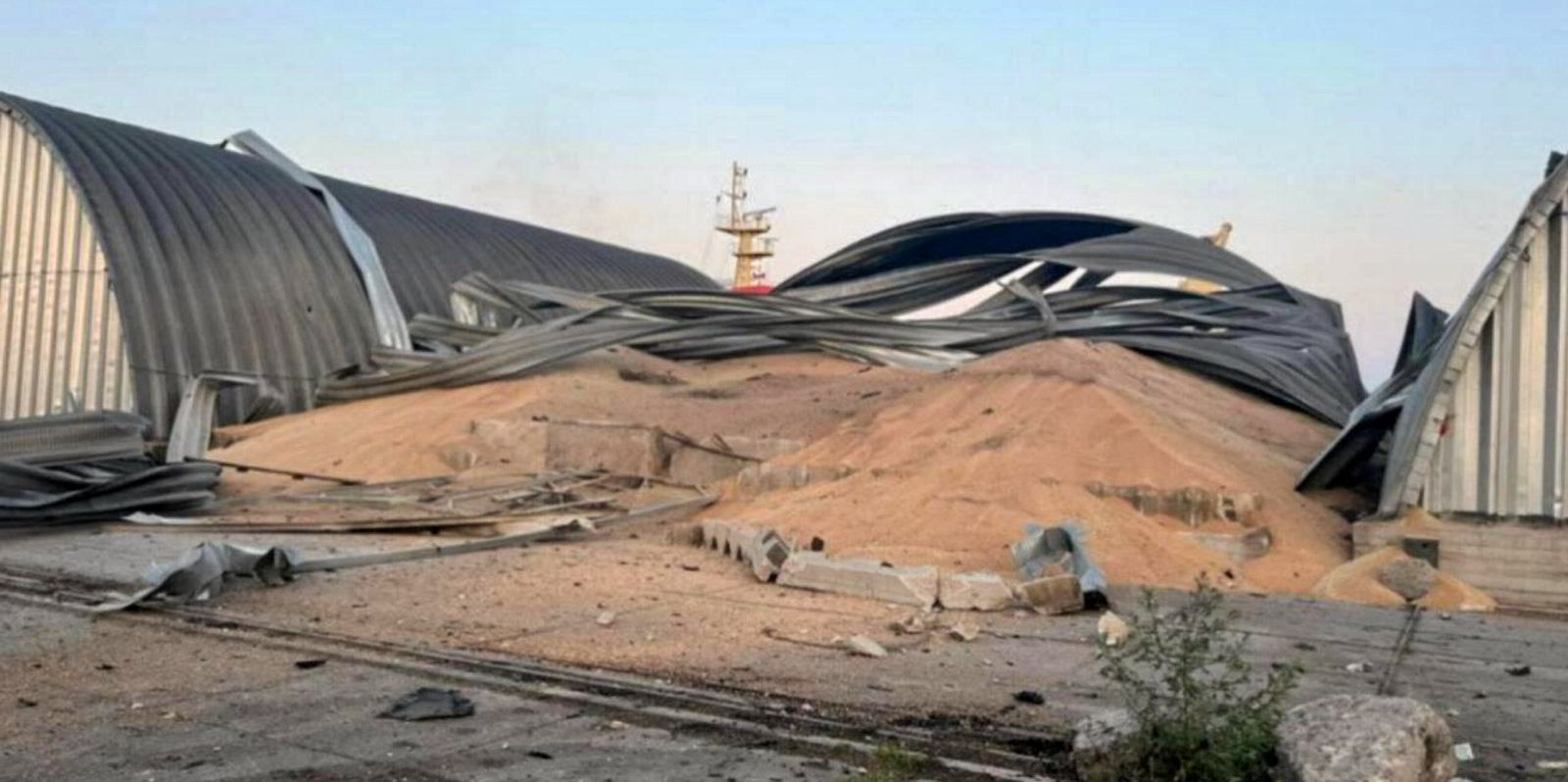

As if problems created by nature were not enough, Russia on 24 July attacked grain silos at the Danube river ports of Reni and Izmail — locations that were previously considered safe due to their proximity to Nato member Romania.

UK diplomats even warned publicly on 25 July that Moscow may be actively pursuing plans to lay mines and attack commercial Black Sea shipping.

The Danube attack has so far remained a one-off. Ship traffic has not stopped in the area but it did scare shipowners and insurers, increasing freight rates on the niche trade.

“Freight rates jumped in recent days … and the terminals are likely to operate only during the daytime for some time, implying a slower overall pace,” Black Sea agricultural market analyst Andrey Sizov tweeted.

News for seaborne shipping may not be so bad.

The backlog of ships active in the BSGI had dwindled to 29 when Russia killed the grain deal, suggesting that the market likely absorbed the overhang more or less easily.

Longer tonne-miles beckon, as providers look for plentiful grain elsewhere.

“The main alternatives will be Canada, Russia, the US, Argentina and Brazil, probably leading to an increase in tonne-miles to markets in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, and eventually absorbing the hit that freight rates might have [taken] from the suspension of the grain corridor,” Xclusiv wrote.

Ukraine counter-threats

Russia will undoubtedly try to take a piece of that action, but it will be no walk in the park.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has much less firepower to inflict damage in the Black Sea than Putin. However, he has demonstrated he can also cause considerable harm.

On 20 July, the government in Kyiv announced a counter-blockade, threatening to attack ships approaching Russia’s Black Sea ports.

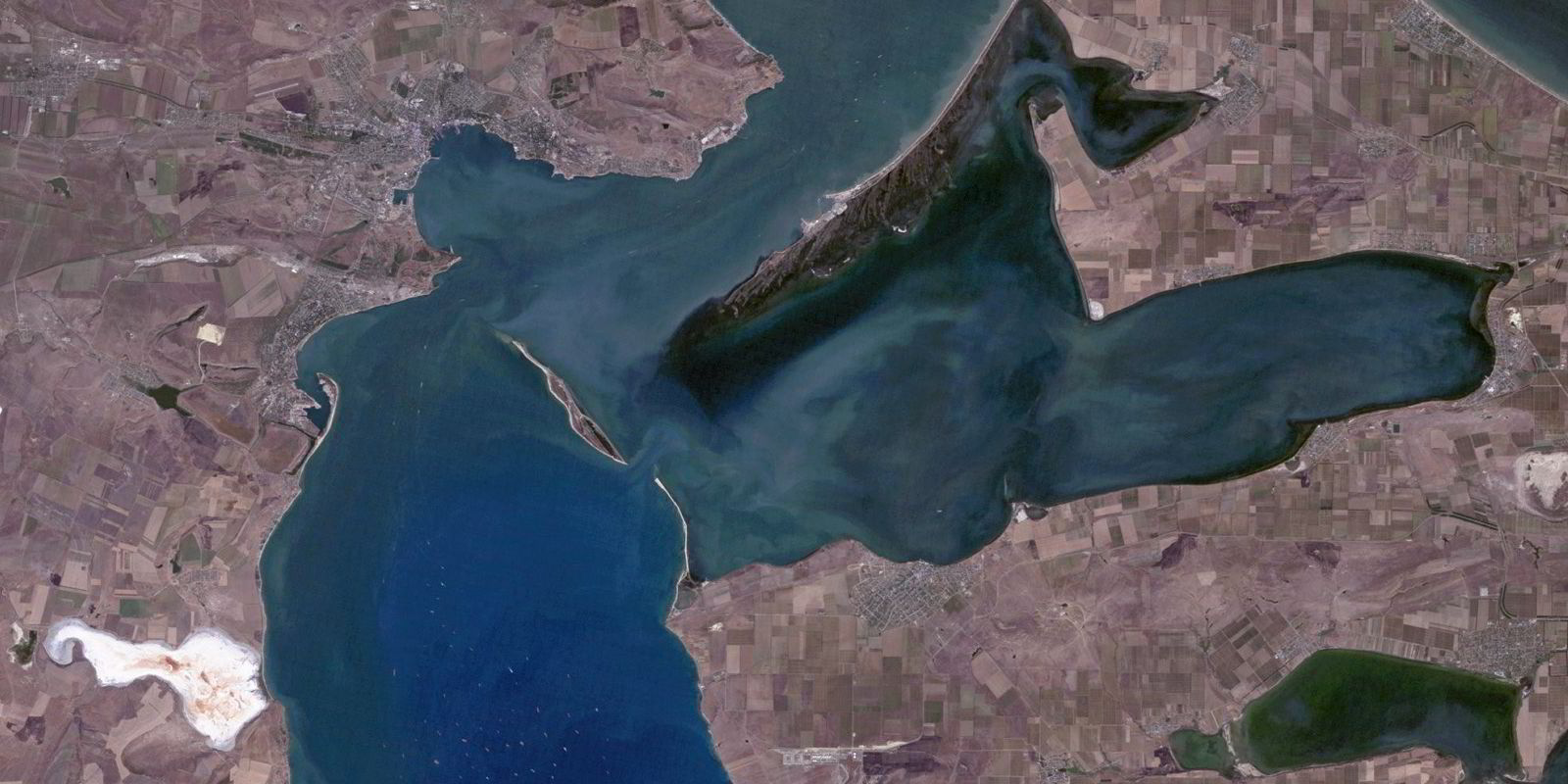

Three days before, sea traffic through the Kerch Strait was disrupted after Ukraine damaged a car and rail bridge there.

Ship traffic has resumed there since, but not smoothly.

On 24 July, Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) announced that all vessels passing through the key waterway, which links Russian-controlled waters in the Black Sea and the Azov Sea, will be henceforth subject to extra checks by secret police agents.

That might put a damper on Russia’s Black Sea dry cargo trade, which has been flourishing, despite the sanctions — partly helped by grain from occupied areas.

According to official Russian figures, transshipment of dry cargo exports from the Black Sea basin rose at an annual pace of 33% in the first half of this year to 71.8m tonnes.