Russian coal exports look set to undergo a dramatic cut next year, though the underlying cause may surprise you.

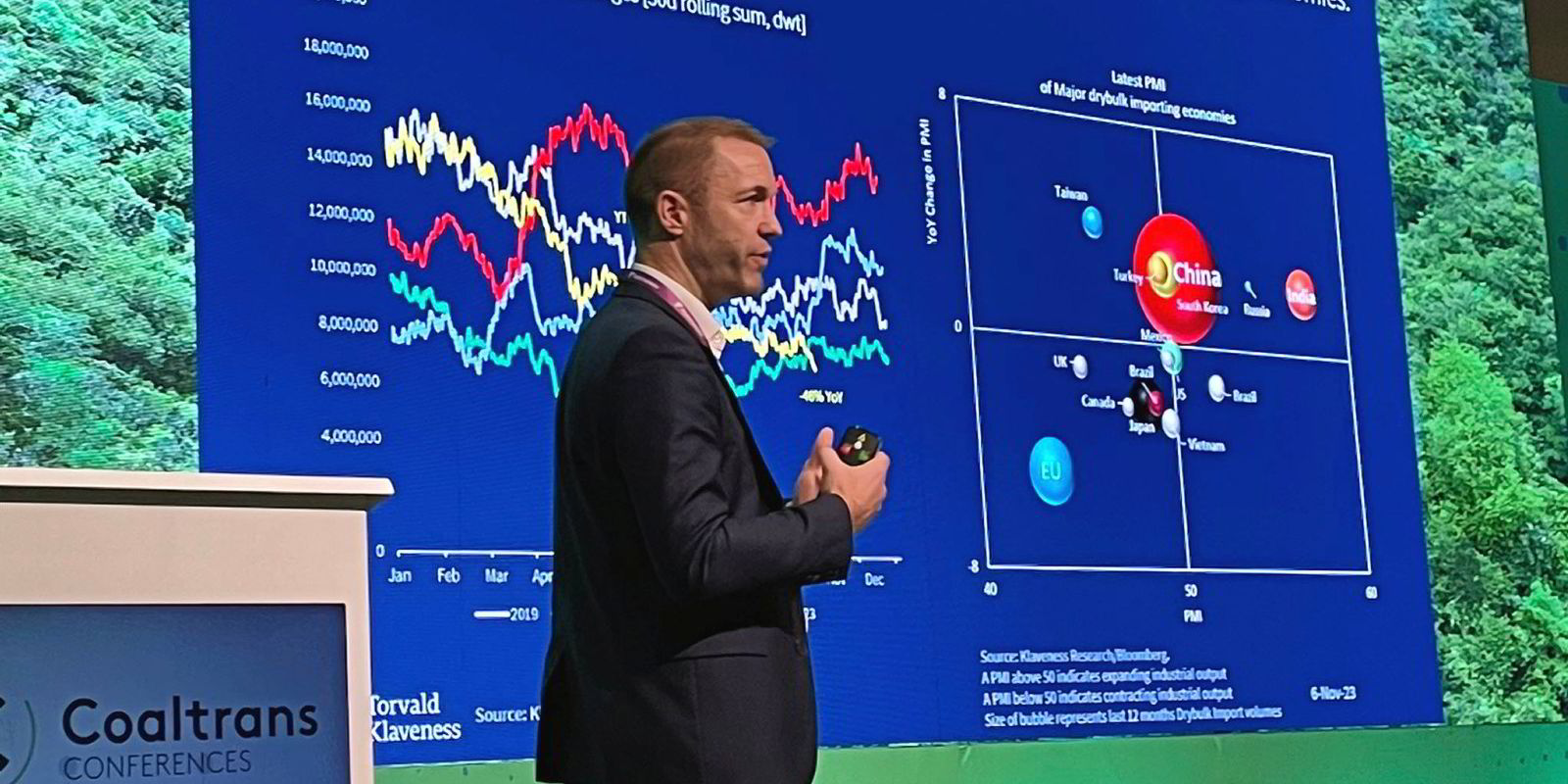

Peter Lindstrom, head of Klaveness Research, said loadings of Russian coal at its Atlantic and Black Sea ports are up by 16% this year to date, in comparison with the same period in 2022.

Trade sanctions on Russian coal have succeeded in cutting imports into Europe from 40% of market share as of 2021 to zero.

Russia has managed to compensate for the loss of these Europe-bound volumes by redirecting exports to Turkey, India and China and these longer-haul voyages are positive for dry bulk freight, Lindstrom said during the World Coal Leaders conference in Madrid on Monday.

However, Russian coal exports are expected to shrink by around 10m tonnes per year, but sanctions have little to do with it.

Rather, Russia’s government has prioritised rail logistics for its military as it continues its war in Ukraine, which means less capacity is available for moving coal. This is expected to hit exports going forward and in 2024.

Rodrigo Echeverri, head of research for commodity trader Nobel Resources, told the conference that “for Russian coal flows to work properly, it needs to be shipping out of four locations”.

Lack of available rail capacity means Russia’s export hubs are now concentrated in the east of the country, which has created a lot of logistical challenges and very distorted trade flows, he explained.

Sareena Patel, co-head of coal, metals and mining at analysis firm McCloskey, said the coal market has become “much more global” since Russia invaded Ukraine.

India has upped its imports of Russian coal since the war broke out, but price dynamics have meant that volumes have remained relatively small compared to other suppliers.

Steelmakers in Japan and South Korea have been hit hard by high energy prices and have turned to Russian coal as a relatively cheap and readily available energy source, but this trend looks set to die out, Patel said.

South Korea’s government has asked state-owned power-generating companies to cease importing Russian coal and imports will fall as new legislation comes in, Patel said.

Longer-haul voyages have typified the coal trade since war broke out in Ukraine and are here to stay, which will continue to support tonne-mile demand for bulkers.

Not about Europe

Another clear message from the conference was that European demand for coal is dying. Imported volumes this year to date are down by just over 20% when compared to last year.

“It’s not about Europe. Europe was a thing that happened, but we’ve all moved on. That’s why I live in Singapore and not London,” said Echeverri.

Reloadings and subsequent re-exports of coal cargoes in Europe have emerged as an interesting quirk as part of this redrawing of global coal trades, according to Alexandre Claude, CEO of cargo tracking platform DBX Commodities.

Small volumes of coal imported into Europe from international suppliers are being reloaded and re-exported from countries such as Spain and the Netherlands to destinations like Morocco and India plus a few other countries, Claude told the conference.

“What we are seeing in Europe is that things are becoming more flexible, not only from the power side but also from the ports side,” Claude said.

These reloadings are being driven by the arbitrages in price for coal in Europe and outside of Europe, he added.

The US, Australia and Colombia remain the biggest suppliers of coal to Europe.

More volumes of Colombian coal are also flowing to the Far East because Colombia has deepsea capesize ports that have better access to Asia than the US, for example, Claude said.