Top foreign ministry officials of both Russia and Ukraine expressed serious reservations over the weekend about United Nations’ efforts to reopen a UN-led Black Sea corridor for Ukrainian grain.

This seems to be dashing any hopes that the consensual deal, under which commercial vessels safely carried more than 30m tonnes of foodstuffs out of Ukraine, can be revived any time soon.

Ukraine seems instead set to push for an alternative corridor — in the teeth of Russian opposition and despite the fact that Kyiv lacks the arms needed to protect such a corridor and war risk insurance to cover it.

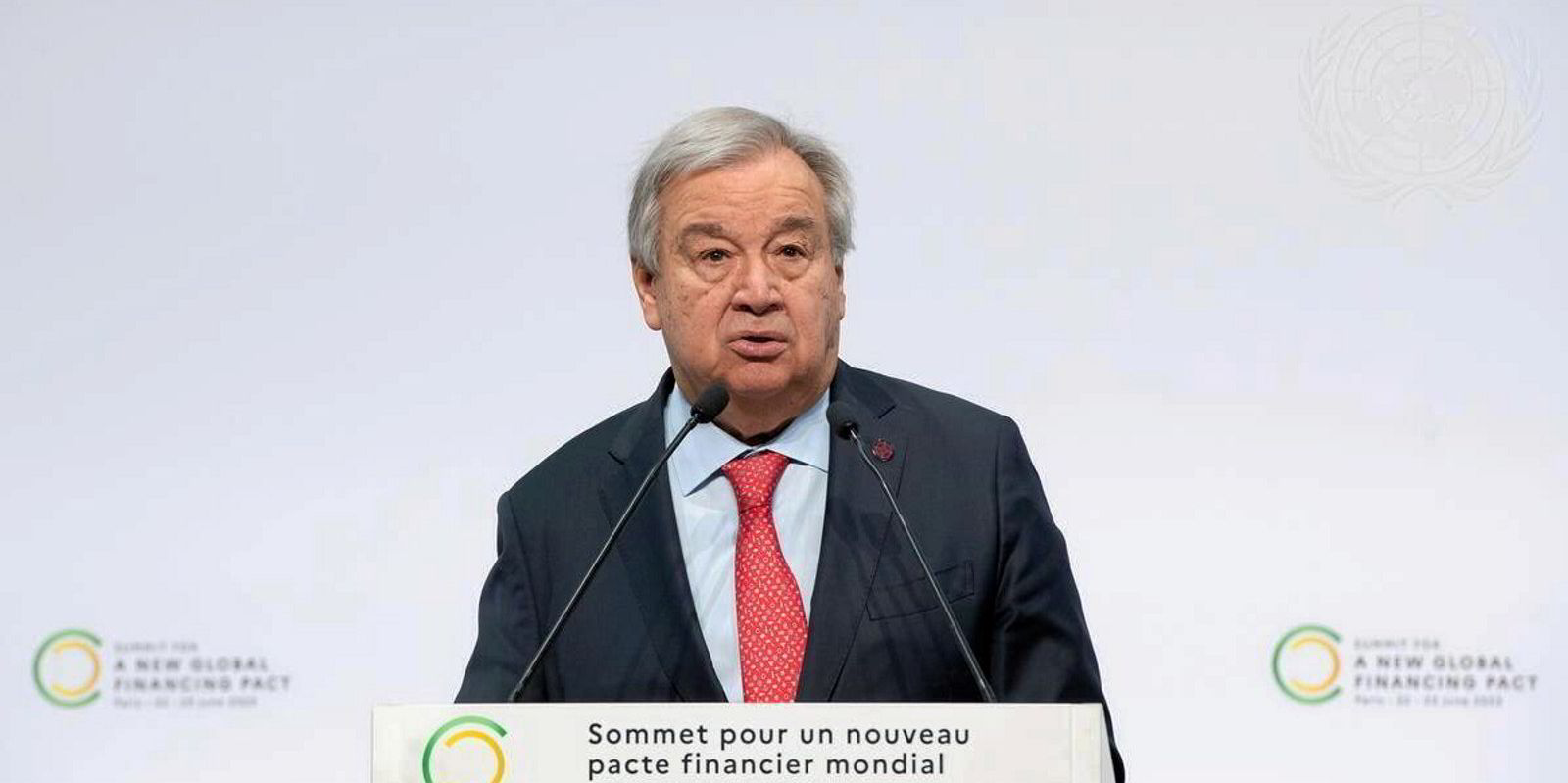

As UN secretary general Antonio Guterres was still awaiting Russia’s official response to proposals about how to reopen the Black Sea Grain Initiative, Kyiv rushed on Friday to reject any diplomatic solution that would involve key concessions to Moscow.

“Loosening the sanctions regime against Russia in exchange for reviving the grain deal will be a victory for Russia’s food blackmail and an invitation for Moscow for new waves of blackmail,” Ukraine foreign ministry spokesman Oleg Nikolenko tweeted on Friday.

“It is crucial to bring Russia back to its obligations, not increase its sense of impunity,” he added.

Moscow withdrew its support of the grain initiative in July, arguing that during the deal’s 12-month operation the UN did nothing to honour a parallel agreement that would facilitate the export of Russian foodstuffs and ammonia and remove obstacles to the insurance and finance of their transport.

Speaking late last week, Guterres and other UN officials confirmed that they considered Russian demands a key factor in resuming the grain corridor.

“We remain actively engaged in aspects related to the access of the Russian Federation to both financial markets and to different other aspects in order to facilitate its exports,” Guterres’ deputy spokesman, Farhan Haq, told reporters.

The same view was also reflected separately in a declaration of the G20 published on 9 September, in which the group called for “immediate and unimpeded” deliveries of grain, foodstuffs, fertilisers and ammonia from both Ukraine and Russia.

Speaking to reporters on Friday, Haq dismissed criticism that the UN proposals help Russia circumvent Western sanctions.

The UN official argued that Russian grain and fertilisers are not directly under sanctions and that the UN was merely trying to “enhance” both warring parties’ food exports in the interest of global food security.

Moscow remains skeptical

Russia has not officially responded to the UN’s proposals yet.

Speaking at the G20 summit in Delhi on 10 September, however, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov suggested he did not see a lot of mileage in the UN proposals.

Moscow’s concerns focus on UN ideas to reconnect Russia’s Agricultural Bank Rosselkhozbank to the SWIFT global interbank payment system.

“No one promised, including Mr Guterres, that Rosselkhozbank would be returned to SWIFT,” he told reporters after the end of the summit.

“They are trying to persuade us to agree to a completely unrealistic scheme so that the branch of Rosselkhozbank in Luxembourg performs this function — this branch does not have a banking license, it has exhausted its capabilities and will close,” Lavrov added.

The Russian foreign minister also said he could not understand how exactly Guterres proposed involving Lloyd’s of London in providing war risk cover for a revived UN grain deal.

Lloyd’s chief executive officer John Neal said on 7 September that his group might provide insurance for Ukraine-bound vessels within a UN framework.

This is not the first time that Moscow is treating UN proposals with skepticism, claiming they fall short of Moscow’s original agreements with the UN and that their implementation would be resisted by Ukraine and the West.

“I expressed gratitude to Antonio Gutteres for what he his doing but all these efforts are doomed in a situation where the West only promises,” Lavrov reiterated on Sunday.

Attacks pile on

In the meantime, Russia has been dramatically stepping up its attacks on Ukrainian port infrastructure at Odesa, Chornomorsk and the Danube.

Drones hit those targets at an unprecedented pace of five nights out of the last seven, causing large-scale damage to oil depots, elevators and grain store facilities.

Ukraine, meanwhile, appears to be spending more diplomatic capital on efforts to establish its own, independent grain corridor rather than on efforts to revive the UN-led one.

Ukraine last month registered a new Black Sea route with the International Maritime Organization, closer to Ukraine’s shore.

The government in Kyiv even managed to send four ships previously trapped in Ukraine through the corridor.

None of these ships was carrying grain, however, and it remains doubtful if the experiment can be replicated on a larger scale.

Kyiv will find it very hard to resume seaborne grain exports on its own, given its lack of air defences and insurers’ unwillingness so far to provide war risk cover for inbound ships under the threat of Russian arms.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, therefore, urged UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak on 7 September to help provide air cover for Odesa.

Mediator Turkey, however, said that no grain deal could work without Russia’s consent.

“A process for the grain issue that excludes Russia is unlikely to be sustainable,” the country’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan said after the G20 summit in Delhi.

At the same time, Russia’s own seaborne grain exports continue at a brisk pace — despite Western sanctions and Ukrainian threats to disrupt the country’s maritime Black Sea trade by attacking ships and the key Kerch bridge.

As TradeWinds reported earlier this week, Russia, Turkey and Qatar are even in talks to set up a separate, mini-corridor to export one million tonnes of Russian grain to poor African countries.

The three countries are looking favourably on the scheme and their officials will meet soon to discuss details, Russia’s deputy foreign minister Sergei Vershinin told the TASS news agency on 8 September.