Efforts to bring battery-powered vessels to US waters are building steam, as a mix of state regulatory requirements and federal funding priorities fuel interest in emissions-cutting technology.

After already finding a place in the offshore vessel market on the US Gulf Coast, batteries are featuring in investment plans across the US ferry sector, and ports on the west coast are looking to electric tugs.

In the ferry market, electrification is expected to become customary for new vessels thanks to funding priorities of the Joe Biden administration.

John Reeves, director of business development for US naval architecture firm Elliott Bay Design Group, said: “Particularly in the ferry world, if your vessel does not have some aspect of reduced or zero emissions, it’s not going to get federal funding.

“Pretty much, every new ferry right now is going to have some level of electrification or reduced emissions.”

In a project involving Elliott Bay Design Group, Maine’s Casco Bay Lines received $3.6m in federal grants for the hybrid-electric propulsion system on the 599-passenger, 15-vehicle ferry that it recently ordered at the Senesco Marine shipyard.

In the west of the country, Elliott Bay Design Group has also been supporting Washington State Ferries as it pushes forward with a plan to build five hybrid-electric newbuildings and convert its largest ferries — the 2,499-passenger, 202-vehicle Jumbo Mark II-class vessels.

In both cases, while the vessels will be charged on shore and will be able to ply their routes on electricity alone, they will still have diesel engines on board.

Point-to-point plus

For most US ferry operators, Reeves said short point-to-point routes are well suited to electric vessels, provided they have access to the electrical grid.

Edward Schwarz, vice president of sales for marine systems at technology firm ABB, said he thought at first that US shipping companies would be hesitant to adopt battery technology. But he admitted that interest has been surging much faster than he anticipated.

“I’m so happy to be wrong,” he said. “With the federal funding that’s available, with the ageing infrastructure of the ferry fleet, ... we’re seeing a lot of interest.”

He added that early adopters not only see battery technology as something they have to adopt, but also recognise that electrification will be a big push.

While battery technology has a limited range that keeps the focus on short-haul shipping, Schwarz said battery technology is a much easier solution than alternative fuels, with lower maintenance and energy that is produced by a utility rather than generated onboard.

The move towards batteries is not driven by Washington DC’s money alone.

Advances in battery technology and operational experience by operators of battery-powered ferries in Europe have increased comfort levels with electrification.

Will Ayers, chief electrical engineer at Elliott Bay Design Group, said: “I think the marine battery racks right now are much safer than grid energy storage. We have these protections that they don’t really have.

“And I’d say the marine batteries are actually safer than even automotive.”

Tugging for batteries

In the tug sector, tightening emissions rules on harbour craft by regulators in California are also fuelling a search for zero-carbon options, and ports are looking to go electric.

Jacksonville-based shipping conglomerate Crowley is developing an all-electric tug — the eWolf — that will operate at California’s port of San Diego from mid-2023.

And that’s just the first. Alisa Praskovich, vice president of sustainability at Crowley, said the company forecasts more across the west coast, potentially replicating on the east coast.

“I would say there’s a fleet in our future. It’s not a matter of if, it’s just when,” she told TradeWinds.

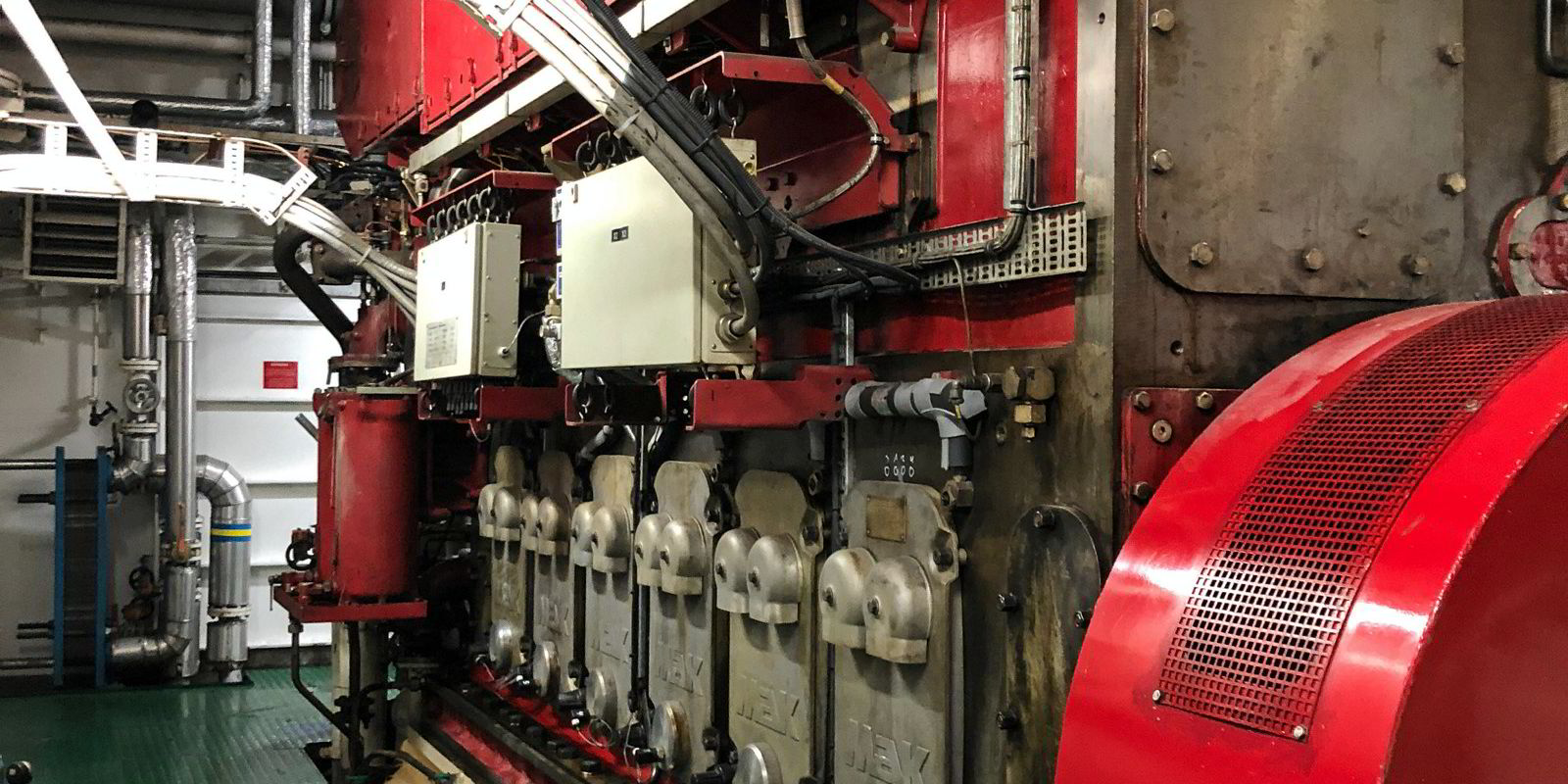

On the US Gulf Coast, batteries are already playing a role in the offshore vessel sector, with New Orleans-headquartered Harvey Gulf International Marine leading the charge with a fleet of five vessels, including four that also run on LNG.

The batteries allow the platform supply vessels to optimise fuel burn in transit and, during dynamic positioning operations, operate on one engine instead of two.

Chad Verret, executive vice president at Harvey Gulf, said the company plans to add batteries to four more vessels.

Combined with real-time emissions monitoring on the vessels, he said Harvey’s focus is on measuring and reducing emissions now rather than waiting for alternative fuels such as hydrogen and ammonia.

“I’ll be out of the marine business before hydrogen is even considered to be acceptable,” he said. “It’s the champagne fuel of the future. And, guess what? Shipping can’t afford to be drinking champagne fuel.”