Readable insider accounts of European policymaking are a rare occurrence in Greek-language literature.

The shipping community should therefore consider itself lucky that Jazz Society, which hit the bookstores in September, was written by one of their own.

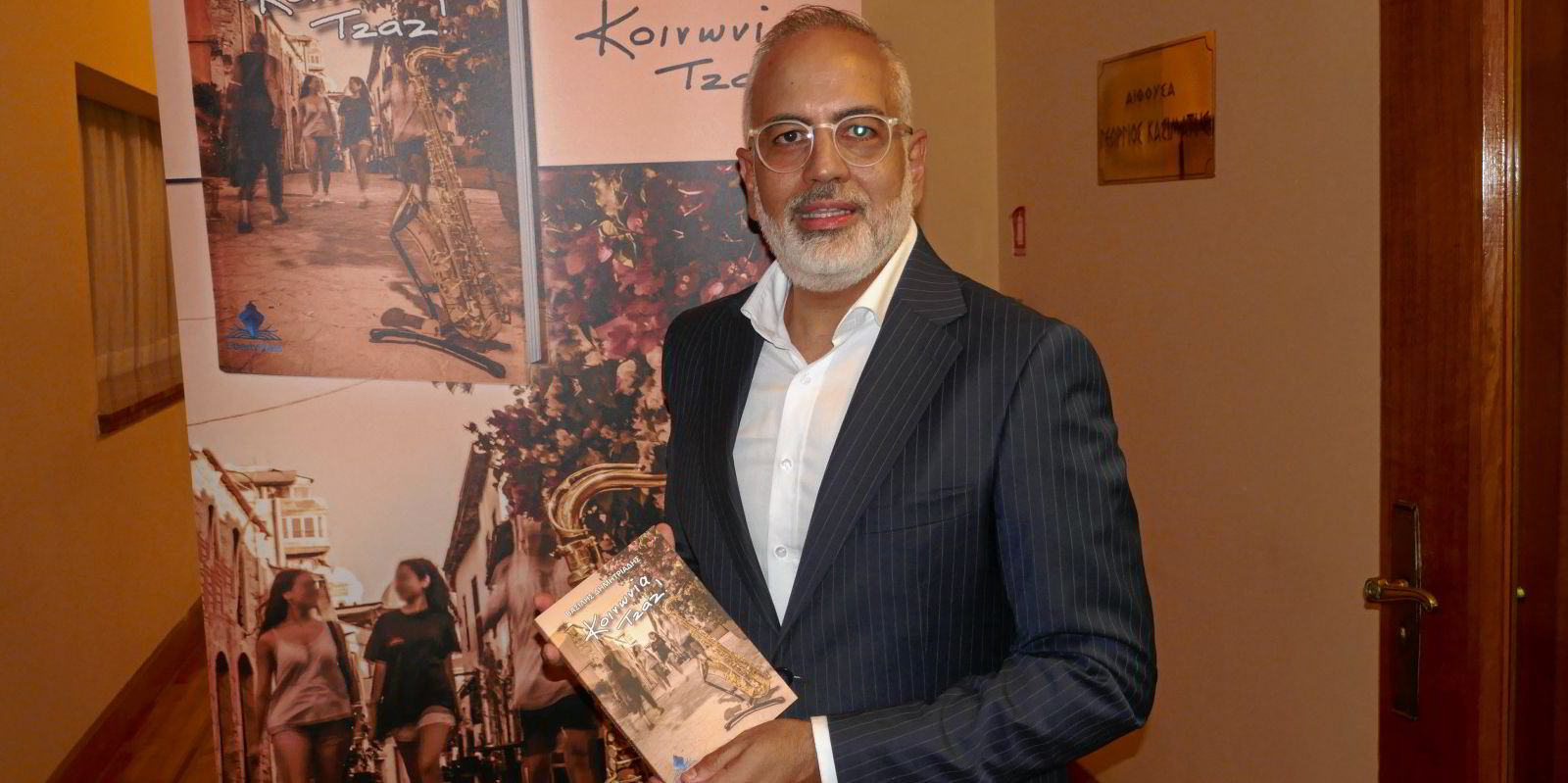

Author Vassilios Demetriades, 51, has lived and breathed international maritime policy for 25 years in the Cypriot government and at the European Commission in Brussels.

This period coincided with his country joining the European Union and the bloc becoming ever more ambitious in its attempts to regulate international shipping.

That presented Demetriades, who was Cyprus’ deputy shipping minister between 2020 and 2023, with a quandary: how does Cyprus — a giant in shipping terms but a minnow in terms of population — influence EU maritime policy with a paltry four votes out of a total 345 cast in the European Council?

“It’s a drop in the ocean,” Demetriades writes in his book, thinly disguised under the alias of Alexander Kanellopoulos, a Cypriot official arriving in Brussels to represent his country.

One obvious solution would be to team up with other shipping heavyweights, such as Greece and Malta. That, however, hardly makes a difference, since it brings in just 15 more votes.

Equally useless is trying to convince EU peers with diatribes about the importance of shipping and global International Maritime Organization rules, as his political masters in Nicosia often instructed him to do.

“Being both small and arrogant is a guaranteed recipe for failure,” Demetriades, aka Kanellopoulos, writes.

In a world where planting a “may” instead of a “shall” in a draft EU directive can make all the difference, the answer is horse-trading. “Compromise is the name of the game,” he writes.

One way to do that is to seek support from landlocked EU countries uninterested in maritime matters, in exchange for Cypriot backing on issues that are dear to them but irrelevant to the little island republic.

“What do we care about rails and inland waters?” asks Demetriades, whose country has no trains or rivers.

Politicians are not the only people well advised to be sensitive to outsiders’ interests and views.

The former cabinet minister does not mince words when it comes to criticising shipping’s introverted attitudes: “It is a closed community that displays its love for what it does in a strange way.”

Like a congregation of the faithful, maritime conferences resemble a litany.

A passage in Jazz Society reads: “Always the same flock making the same statements, how important their sector is and that others don’t understand them, think differently and ignore them.

“Like a theatrical super-production addressing a very small, select audience by invitation only, in a theatre that could fit at least three times as many people.”

Demetriades recommends that the industry “open the doors and windows” instead, by inviting even the “green Taliban” to debate. “If we try and they still do not listen to us, then we will have all the right in the world to complain.”

Demetriades’ public service career ended earlier this year after a change of government in Cyprus.

He is now a business consultant with VisionDo, a company he founded that advises clients on matters from environmental, social and corporate governance factors to EU policy, regulatory challenges and EU co-financed projects.

Demetriades entertained hopes this year of putting forward a bid to become secretary general of the IMO, but that ultimately came to nothing.

In a short, rather cryptic chapter in the book in which no names, countries or even the IMO itself are mentioned, insiders will recognise a veiled reference to the episode and the bitterness it left Demetriades with.

“The foreigners wanted you and we [Cypriots] didn’t care,” Alexander Kanellopoulos tells a fictitious personality he bumps into at a cafe in Cyprus.