Over-reliance on automated weather routeing systems could lead to a disaster like the El Faro sinking, warns an executive at a firm that mixes artificial intelligence-based forecasts with human knowledge.

“If you trust 100% in automated routeing solutions, there are going to be problems,” said Jesse Vecchione, regional head of sales and marketing North America, of Weathernews at a press briefing.

“My fear is that within the next five years or so there will be a cathartic event similar to El Faro; because there is a company offering an automated weather routeing solution but there are no trained people watching the routes going out. There is going to be an accident. I don’t want this to happen.”

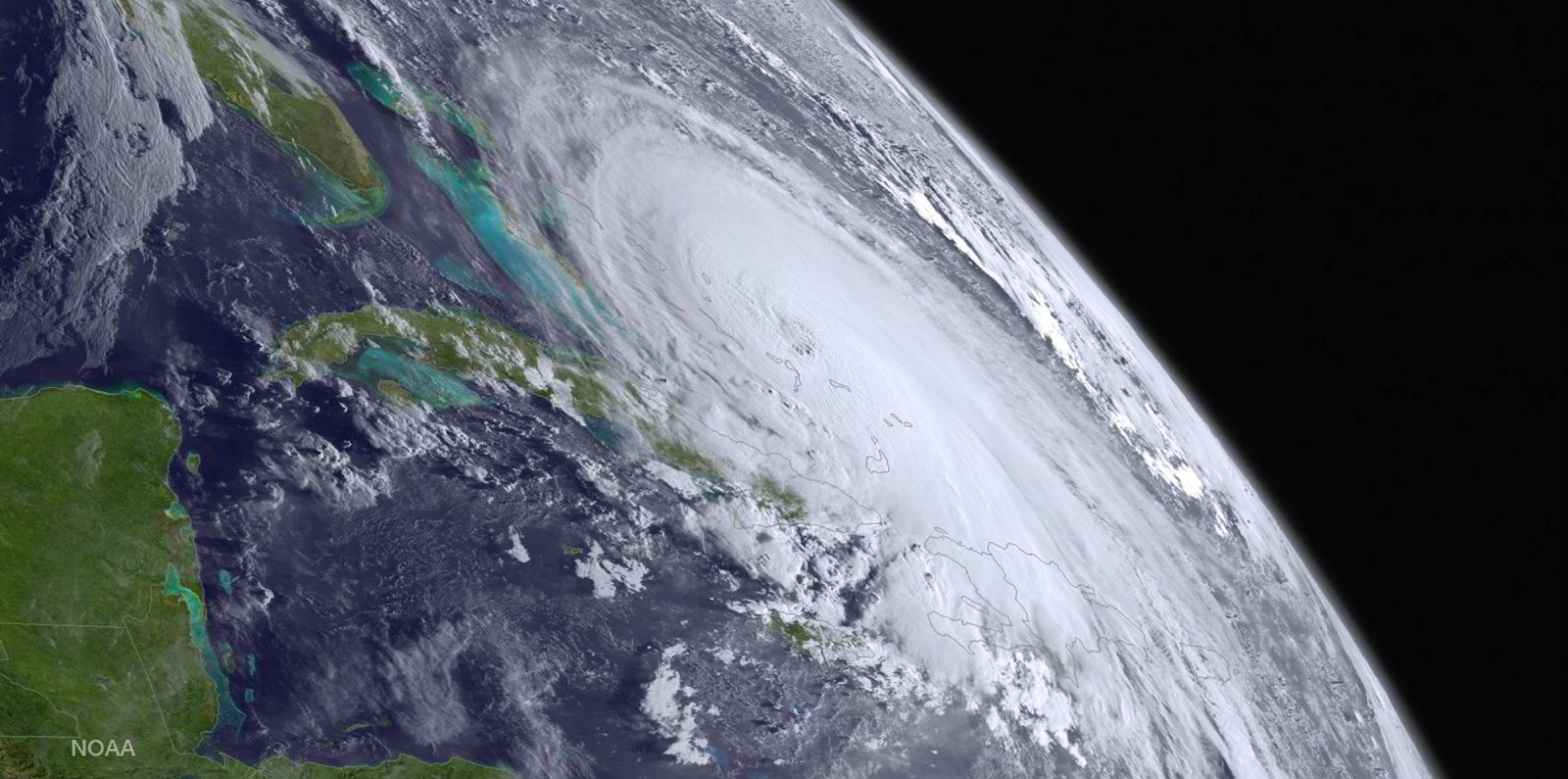

The 5,330-lane-metre El Faro (built 1975) sank during Hurricane Joaquin in 2015, killing all 33 crew after the captain’s use of incorrect weather data led to a lack of action to avoid the storm.

Vecchione, who is a former weather forecaster for the Japanese-owned company that was set up in 1986, said it is important to keep a “human in the loop”.

He claimed that some of the routes suggested by automated systems developed by start-up digital developers that compete with Weathernews could lead to sinkings.

Vecchione said he was not suggesting automatic solutions cannot be used but insisted they need to be checked to ensure the models are not missing potential dangers. Weathernews has built and uses its own data-based forecasting systems alongside human forecasters.

“Lots of times the route AI is drawing is not taking into account pattern recognition. Lots of models don’t understand, for example, low pressure systems that develop in the middle of the Atlantic or Pacific oceans: they could be weak in terms of low pressure but the pressure gradient around that could be so great you could add days to a voyage in very heavy conditions.”

He also pointed to bombing low pressure systems, hurricanes becoming extra-tropical, heavy swells off South Africa and flip-flopping weather patterns as examples of issues that can be missed.

Weathernews provides information and advice to 10,000 ships at sea at any one time, with clients roughly balanced between owners and charterers. It gathers information from ships and planes as well as satellites and observation stations.

Container lines, such as Maersk, are among its biggest customers due to their need to adhere to tight sailing schedules.

Storm tracking

Occasionally there are challenges where a bulker charterer wants a vessel to go through heavy weather to deliver a cargo and, Vecchione said, then it becomes necessary for Weathernews to try to convince the operators that is better to be safe than sorry.

Addressing potential for routeing conflict between owners and charterers over the International Maritime Organization’s Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII), Vecchione said he felt it might be necessary to rejig the CII index to de-emphasise time in port, which can skew vessel ratings.

Weathernews can provide forecast up to 15 days in advance, but he said nothing beyond three days could be regarded as fully correct as conditions can quickly change. After five days, a forecast might only be 30% accurate.

Although difficult to systemise nuances of weather behaviour, Vecchione said he expected automated forecasts to improve over time.

Weathernews has released a platform that will interact with the IMO-compliant Electronic Chart Display and Information Systems, or ECDIS, alongside checking by trained personnel, and it has a partnership with Norwegian navigational software group Navtor.

The platform will develop up to nine route options, ranging from whether ships want to save time, fuel or use a specific route.

Weathernews compares its forecast routes with actual routes taken by ships to show return on investment rates that Vecchione said can vary from three to one, comparing fuel and time savings with cost, up to 15 to one.

Large container ships tend to get the best results as they will burn a lot of fuel if they go full speed, with lower outcomes tending to be where Weathernews cannot suggest an engine setting to a ship’s operator.

It is also developing a system, expected to be ready by the end of the year, to provide insurance that its estimated times of arrival will be dependable — paying out if it is wrong by a specified margin.