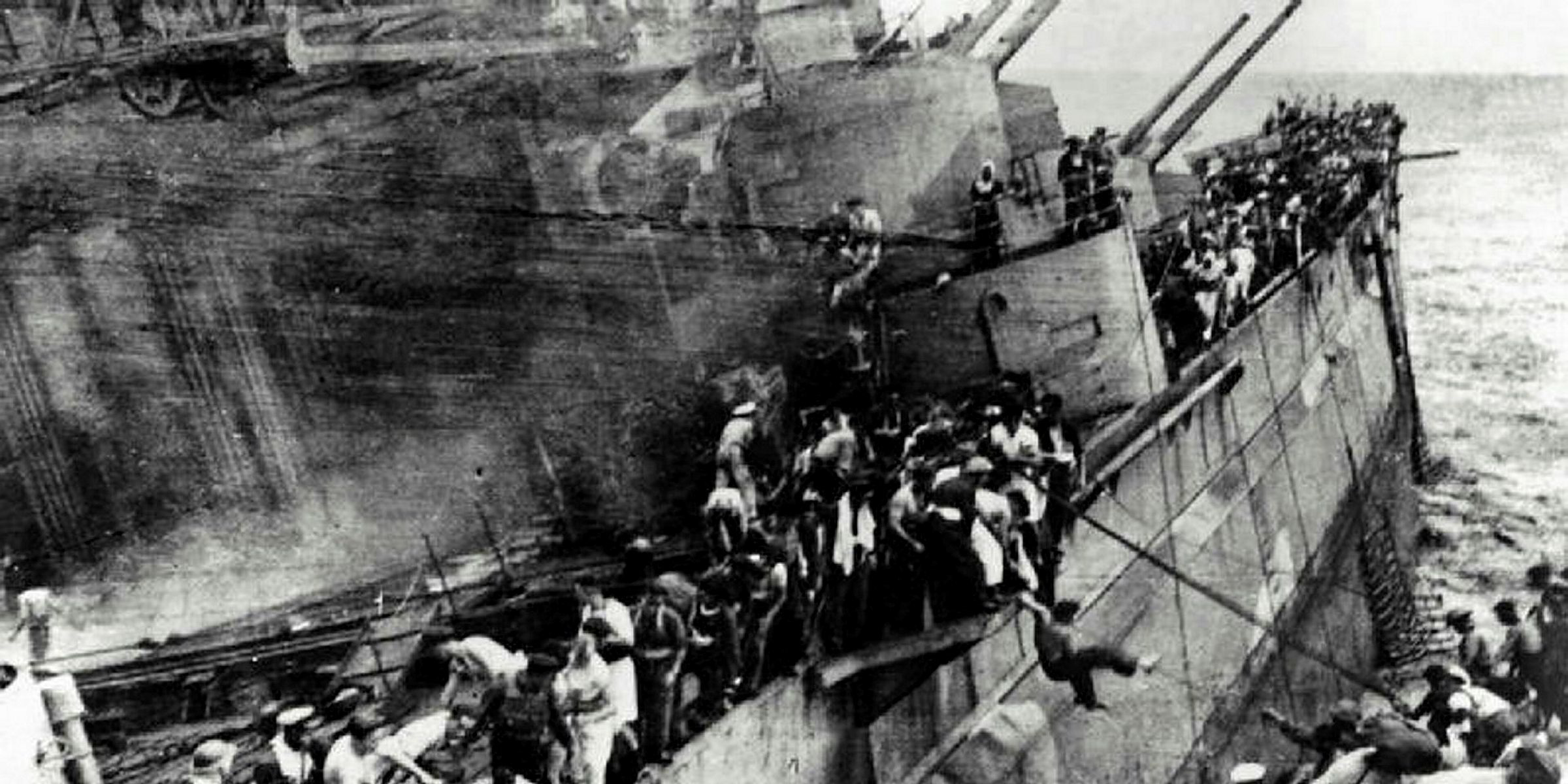

On 10 December 1941, British Royal Navy Admiral Sir Tom Phillips made a bad call and military history when his Force Z flotilla — dispatched to the Far East by UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill to head off Imperial Japan's attack on Singapore — was taken by surprise by Japanese torpedo bombers.

Admiral Phillips refused to call for air cover for fear of breaking radio silence. He went down with his flagship, the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, and Singapore fell to the invaders.

"I reckon this must have been the last battle in which the Navy reckoned they could get along without the RAF [Royal Air Force]," RAF fighter ace Tim Vigors said to military historians 50 years later. "A pretty damned costly way of learning."

The HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, which was also sunk, served as Admiral Phillips' final resting place and that of 840 sailors, until the vessels were plundered in the past couple of years.

"They must have been looking for non-ferrous metals, or maybe historical artefacts," one scrapping playertold TradeWinds. "Not the steel, after all those years underwater."

But the grave robbers must have known what to do with the steel they found.

According to the UK's Mail on Sunday newspaper this week, up to 10 Royal Navy vessels from World War II that lay corroding off the coasts of Malaysia and Indonesia for nearly 80 years have recently been targeted by what it calls Chinese "pirates".

The scavengers position crane barges above the wrecks and drop large anchors onto them to break up their hulls. Then they dredge up the pieces.

The pieces may contain the remains of victims, and Indonesian authorities are now investigating one cemetery where British and Dutch sailors were unceremoniously dumped.

Scrap steel has always been valuable, greed has always perverted the spirit of man, and these ships have always lain unprotected. So why are they being desecrated now?

Over the past two years, China has imposed a series of prohibitions on the import of all kinds of recyclables, including electronics, paper, metal and, most recently, whole ships.

In May, Chinese authorities announced an import ban that essentially meant shiprecycling would be finished by the end of this year. Chinese prices per ldt for imported vessels immediately strengthened, reflecting a wish to stock as much steel as possible. But at the beginning of this month, prices collapsed from their already non-competitive levels. China's breaking yards had given up.

The regulators who are protecting China from the indignity of importing other people's scrap have not found a way to ban the demand for it

"The Chinese green scrapping market is essentially dead," one cash buyer said. "And their volumes were already so small and their prices so low that nobody will miss them from the equation."

Meanwhile, from circuit boards to paper to steel, one person's trash is another person's treasure. Chinese papermills are rumoured to be so starved of discarded paper from abroad that they have begun importing containers full of cardboard boxes, just to pulp them.

In shiprecycling, a similar distortion of the market is underway — whether or not it lies behind the desecration of the warships.

The regulators who are protecting China from the indignity of importing other people's scrap have not found a way to ban the demand for it — especially as environmental regulations make life hard for China's ore smelters, pushing steelmakers towards electric arc furnaces that only use scrap steel.

China's steelmakers will be chasing scrap where they can get it, and corroded warships will not go far.

Scrapping sources say plans are now underway in Indonesia to convert idled rig yards for green scrapping to replace Chinese recyclers that have given up.

Industry players who have studied this alternative say the cost levels will not make Indonesia any more attractive than China, measured against South Asian scrapping prices — especially when 16 green breaking yards in India that are certified by the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships are now said to be offering prices of more than $400 per ldt.

Still, ship hulls processed in Indonesia may have a better chance of making their way to Chinese mills than in ship form, import ban or not. And, without its own shipbreaking industry, China will have to absorb the cost.