There is nothing novel about human fear of new technology, but is the current march of the robots of a different order of threat altogether? Portside activities have already undergone a high degree of automation, cutting jobs, and now the next wave of maritime digital transformation is looming at sea.

Russell Downs, a council member of the Nautilus seafaring union, told a conference last year that 90% of some jobs could be removed through digitalisation and he noted predictions that crewless merchant ships would be used extensively within a decade.

Tony Seba, an academic from Stanford University, told this year’s Nor-Shipping conference in June that shipowners who had not worked out yet what disruption digitalisation could bring to shipping were already halfway on their way to corporate extinction.

Later that month, Rashpal Bhatti, vice president of freight at mining giant BHP, said “safe and efficient autonomous vessels carrying BHP cargo, powered by BHP gas, is our vision for the future of dry bulk shipping”.

Even the International Union of Marine Insurance conference in Tokyo last month was themed around autonomous ships, big data and the Internet of Things representing an “opportunity or threat”.

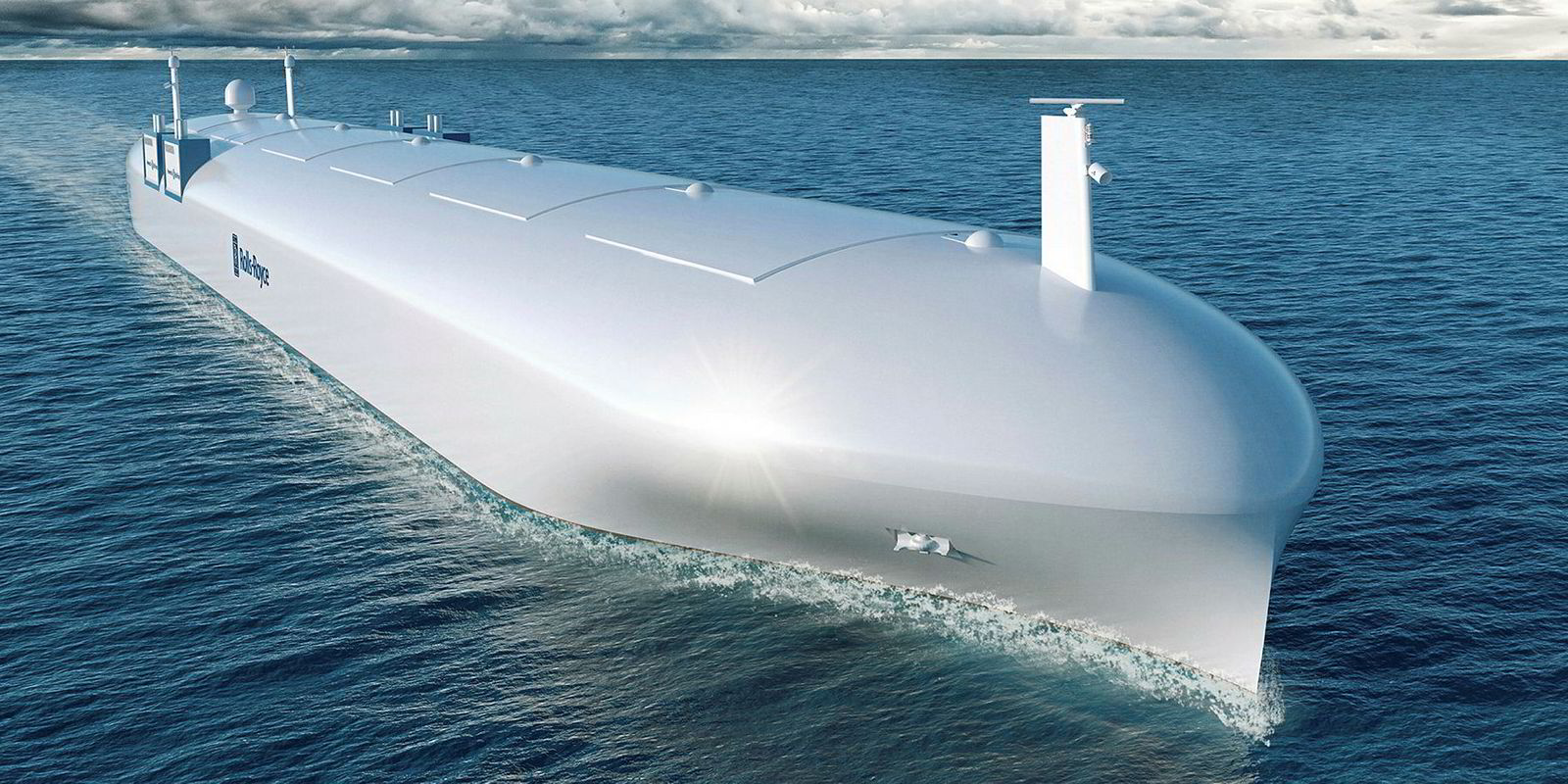

Engine manufacturer Rolls-Royce announced last week that it was teaming up with Google to develop better awareness systems that would lead to “making autonomous ships a reality”.

Let's remember Google has a stock market value of nearly $700bn, more than twice that of ExxonMobil, almost 20 times bigger than AP Moller-Maersk and 700 times bigger than Clarksons.

Next year, Rolls-Royce will undertake a trial with Fjord1, which will see a ferry sailing between Anda and Lote in western Norway — fully automated, but using one human, the ship’s master, for final berthing. Initially, a full crew will be present but eventually they will be removed.

Nautilus, concerned that research projects like this will move to international waters sooner or later, insists the "human element" is an important line of defence against machinery breakdowns and other unexpected events.

There are plenty of other issues to grapple with, not least the dangers of cyber attacks and the disabling of automated ships, union officials argue.

The US Navy weighed in on the military side last year, unveiling what was billed as the world’s first unmanned vessel. The 132-foot (40-metre) Sea Hunter, built for hunting submarines and with a range of 10,000 nautical miles, is now off on a two-year trial.

Over the border, the Canadian Coast Guard has been using unmanned “drone” helicopters to work in inhospitable, dangerous Arctic waters.

A growing number of shipowners and others see technology opening the door to safer, more efficient and cheaper shipments. But they are deeply aware that new International Maritime Organization regulations will be needed before drone vessels are a common sight on the high seas.

Classification society Lloyd’s Register has already developed a prototype Unmanned Marine Systems Code to assess emerging technologies and drone ship safety.

Rolls-Royce says well-trained machine learning models can already perform predictive analytics faster and better than humans.

The company is also arguing that technology and automation can play a big role in reducing carbon emissions, claiming that the removal of a ship’s wheelhouse and lifesaving equipment could bring fuel efficiencies of up to 20%. If true, this would be a major selling point.

Norwegian agricultural products specialist and shipowner Yara International recently laid out plans to operate its first fully autonomous, zero-emissions vessel by 2020. It has commissioned Kongsberg to construct a fully electric feedership capable of carrying more that 100 containers that will be operated (at first) with a crew.

Yara argues that most marine accidents are caused by human error, so the digital world can make shipping safer, not more dangerous.

Japan’s MOL, which is developing artificial intelligence for collision avoidance and other purposes, agrees.

Downs, aware of the Luddites and others who destroyed automated textile equipment in the 19th century, has said that resistance may be futile but the implications must be considered carefully.

In the meantime, don’t look away: the robots are coming.