A shipwreck that claimed six seafarers’ lives and fouled Alaska’s sensitive coastline is the subject of a $4m legal fight in the US nearly two decades after the disaster.

Malaysia’s IMC Shipping and the US Coast Guard’s National Pollution Funds Center (NPFC) are fighting over the last unpaid piece of the bill for the 2004 grounding of the 72,000-dwt Selendang Ayu (built 1998).

A key element in the fight is an elaborate proposal, never carried out, to kill all the rats on Kiska Island in the Aleutians to keep the invasive rodents from eating the eggs and young of the crested auks that breed there.

Kiska is not where the ship grounded, but it is a key nesting ground for the crested auk, whose habitats on nearby Unalaska Island were fouled.

Crevices formed in fresh volcanic rock before it is overgrown by vegetation make Kiska an attractive nesting ground for the crested auk.

Rats like crevices, too, not least when they are lined with fresh auk eggs and auklets. And although rats are not native there, the whole uninhabited archipelago to which Kiska belongs has been known for two centuries as the Rat Islands.

Lawyers for IMC told a court that they spent millions carrying out various directives by US authorities during the years after the spill, including a study of the rat-killing scheme, and deserve reimbursement for everything above a $24m liability cap.

But they claim the Coast Guard has been making up reimbursement rules as it goes along, and has done so arbitrarily, inconsistently, and contrary to the statute.

“Plaintiffs are entitled to, but were denied, reimbursement [for] certain actions that plaintiffs took at the direction of federal and state agencies that were designated as trustees for natural resources,” they told the court.

Under US law, the responsible parties in maritime pollution cases must pay for the clean-up up to a limit based on a vessel’s gross tonnage. The costs beyond that come from an oil spill liability trust fund. The NPFC is the agency within the Coast Guard that disburses the monies from the fund.

The deadly Selendang Ayu disaster, one of the most expensive ever for the Swedish Club, began on 6 December 2004, when the panamax, laden with US soybeans, lost power off Unalaska Island in the Aleutian chain, grounding two days later on its rocky and ecologically sensitive coast. Six persons lost their lives when a helicopter crashed during the evacuation and rescue effort, and 138 km (86 miles) of coastline were fouled.

The environmental remediation included not just the clean-up but also efforts to save endangered wildlife and restore habitats.

In December 2007, three years after the incident, IMC and the one-ship company that owned the ill-fated ship, insured by the Swedish Club, submitted a claim limiting their liability to $23.85m and change. The NPFC accepted that claim over four years later, in January 2012, according to legal filings by lawyers for IMC.

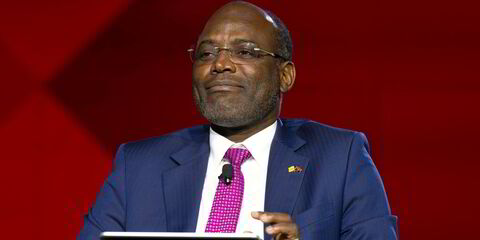

The case is before chief judge James Boasberg of the District of Columbia federal district court.

The ambitious proposal to spray rat poison all over Kiska Island came in 2008 from unnamed US authorities, who acted as trustees of the oil spill liability trust fund and gave directions to IMC in its remediation efforts. One Aleutian Island, Hawadax, had rat poison sprayed all over it from two helicopters, after the summer breeding season was over and the auks were safely gone. That was the end of all the rats on Hawadax.

Nevertheless, IMC was sceptical. Wildlife biologists the shipowner consulted pointed out the rat poison on Hawadax had also killed a lot of bald eagles and seabirds and doubted that the rats were even eating very many auklets on Kiska.

They also doubted the same plan would work there. They pointed out that Kiska is 10 times the size of Hawadax, that rats reproduce so relentlessly that every rat on Kiska would have to be killed to do any good, and that rats on a nearby island would also have to be wiped out because it was close enough to swim.

There were also Kiska’s subterranean rat population to be considered. Imperial Japan occupied Kiska in 1942 and blasted a network of tunnels, which remain. After a poisoning, tunnel rats would quickly repopulate the ratless, post-apocalyptic landscape above.

In the end, IMC spent its money restoring and expanding crested auk breeding grounds instead of killing rats, but not before spending money on studying the US government plan, for which the Coast Guard now refuses to pay.

TradeWinds has approached lawyers for IMC and the Coast Guard for comment.