It may not be a bad thing if container ship supply outpaces demand over the next few years.

Some liner executives believe perpetual disruptions to the supply chain and growing environmental demands will require excess capacity for the industry to function.

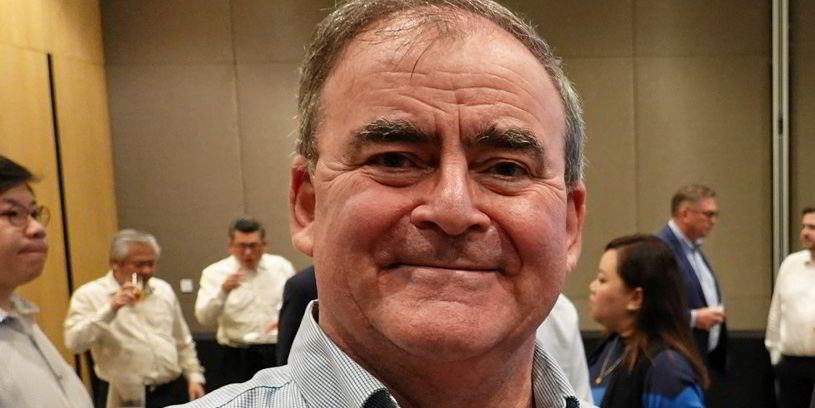

One of those expressing that view is Hapag-Lloyd chief executive Rolf Habben Jansen.

The boss of the world’s fifth-largest liner operator concedes that supply will probably outpace demand by 2026, but he believes that “the notion that supply and demand always need to be in balance is probably wrong”.

With container shipping getting to grips with the energy transition, “we’ll very likely need to sail slower, which will require more capacity”, he told a Capital Markets Day presentation on Tuesday.

“And it’s also not bad if there’s a little bit of spare capacity to react to supply chain disruptions as we see them, for example, now like in the Red Sea.”

The liner sector faces the persistent threat of Houthi attacks from Yemen and an uncertain situation in the Bab el-Mandeb strait.

That still forces many container ships to divert from the Red Sea and Suez Canal route to the Cape of Good Hope, which analysts say is “artificially” inflating tonnage demand.

“Without having some excess ships, we would not have been able to react to that as an industry, whereas we have been able to do that quite well this time,” Habben Jansen said.

It is just the latest in a string of events that the container industry has wrestled with over the past five years, he said, “and I don’t think we’re going to be without disruptions over the next planning period”.

An escalation of the Israel-Palestine situation into a wider regional conflict would expand the high-risk areas for shipping in the Middle East.

Carriers would be compelled to further adjust networks to ensure the safety of crews, vessels and cargoes, with impacts on vessel availability and tonnage supply, argues Alphaliner.

“And as such, I think we need to rethink a little whether supply and demand needs to be completely in balance,” Habben Jansen said.

Liner operators have been taken by surprise by a shortage of vessels available for charter this year.

Alphaliner’s latest survey estimates that there are few idle container ships, with just 0.7% of the world’s 29m teu cellular capacity remaining available on a global scale. This translates to 70 vessels, totalling 203,763 teu, as commercially idle.

Alphaliner said this indicates the container shipping fleet can be considered “fully employed” and there is no “structural” idling.

A market with no slack

Strong tonnage demand has also prompted carriers and shipowners to send fewer vessels to the yards for routine repairs and upgrades this month.

In normal years, the pre-peak season second quarter marks something like a “main dry-docking season”. Capacity in shipyards exceeded 800,000 teu in April last year. This year, however, only 119 units of 522,731 teu are in the dockyards.

The tightening market is reflected by a continued shortage of prompt tonnage, particularly for larger vessels. Carriers are resorting to relets by other operators to fill their immediate demand needs.

The busiest appears to have been AP Moller-Maersk, which is reported to have taken the 9,034-teu UASC Zamzam (built 2014) as a sublet from Hapag-Lloyd for up to four months at about $45,000 per day.

It has also taken the 6,881-teu Kea (renamed Panda 006, built 2013) as a sublet from Tailwind Shipping Lines for two months at around $40,000 per day.

Tailwind took the vessel in February for 36 months at around $38,500 per day.

So what had been projected to be a financially challenging year for container shipping is turning out to be just the opposite.

That, however, could swiftly be reversed if the impetus from the Red Sea disruption eases, in which case capacity management will be difficult, given the scale of cumulative supply growth, argues Clarksons Research.

The shipbroker expects the container fleet will be around 20% larger at the end of 2025 than at the beginning of 2023.

Container volume growth will be reasonably solid next year alongside further reductions in vessel speeds, it added.